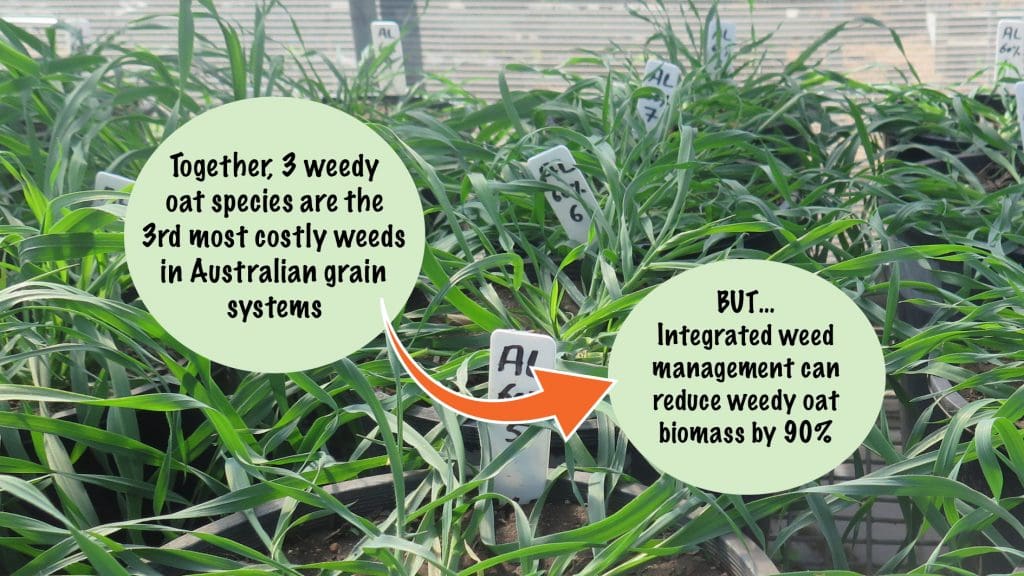

RANKED as the third most costly weed in Australian grain cropping, three weedy Avena spp. – wild oat, sterile oat and slender oat – are estimated to infest over two million hectares, causing crop yield losses of 114,596 t and a national revenue loss of $28.1 million.

In the southern and western regions, the main species found is wild oats (A. fatua), while in the northern region, sterile oats (A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana) is the more problematic species. Both have evolved resistance to multiple herbicide groups in Australia.

QAAFI weed researchers Gulshan Mahajan and Bhagirath Chauhan have recently published a series of papers on their weed ecology studies of Avena spp., providing growers and agronomists with more information to use when formulating integrated management plans for these weeds in crops.

Practical tips:

- Both wild oat and sterile oat can survive in soil moisture conditions of 60 per cent water holding capacity (WHC). Sterile oat even produced seed at 40 per cent WHC.

- Seedlings of these weeds can emerge from a depth of 10 cm, but greater emergence occurred from 2 and 5 cm depths. Emergence commenced at the start of winter (May) and continued until spring (October).

- In a no-till system there is low persistence of seed on the soil surface. A 2-year assault on the weed seed bank can result in complete control of infestations.

- Early emergence plants produce the most seed, but later emergence plants can still produce enough seed to support reinfestation.

- Weed density of 15 wild oat and 16 sterile oat plants/m2 resulted in a 50 per cent reduction in wheat yield. Lower weed density (just 3 plants/m2) can still support reinfestation.

- Sterile oat is a better candidate than wild oat for harvest weed seed control (HWSC).

- Wild oat is best managed through early weed control (pre and post sowing) and strong crop competition.

- An integrated approach to weed management can reduce Avena weed biomass by up to 90 per cent.

Experimental design features

Four related research papers:

- Biological traits of six sterile oat biotypes in response to planting time. https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20507

- Influence of soil moisture levels on the growth and reproductive behaviour of Avena fatua and Avena ludoviciana. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234648

- Seed longevity and seedling emergence behaviour of wild oat (Avena fatua) and sterile oat (Avena sterilis ssp. ludoviciana) in response to burial depth in eastern Australia. https://doi.org/10.1017/wsc.2021.7

- Interference of wild oats (Avena fatua) and sterile oats (Avena sterilis ssp. ludoviciana) in wheat. https://doi.org/10.1017/wsc.2021.25

Detailed findings

Sterile oats growth and seed production for early and late emergence cohorts

Six biotypes of sterile oats were collected from sites in southern Queensland and northern NSW and planted in field conditions at the Gatton research farm in the winter cropping seasons of 2018 and 2019. The weed seed was sown early, mid and late season and the growth and reproductive potential of the six biotypes was monitored.

Averaged across the biotypes, the early planted weeds produced 2660 seeds/plant. Weeds sow mid-season produced 21 per cent less seed and the late-season weeds produced 84 per cent less seed than the early-season plants.

Although seed production was more prolific from the early and mid season plants, the late season plants produced sufficient seed to support reinfestation the following season.

A clean seed bed and competitive crop environment is the best strategy to suppress sterile oat seed production.

Effect of moisture stress on biomass and seed production of wild oats and sterile oats

Seeds of wild oat and sterile oat used in this study were collected from Warialda, NSW, in October 2017 and multiplied at the University of Queensland, Gatton Research Farm in the winter season of 2018. The pot trial to investigate the effect of 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 per cent water holding capacity (WHC) on these two Avenaweed species was conducted in 2019.

Results revealed that wild oat did not survive, and failed to produce seeds, at 20 and 40 per cent WHC. However, sterile oat survived at 40 per cent WHC and produced 54 seeds/plant, suggesting that this species is likely to compete strongly with crops in water stressed situations.

In favourable moisture conditions, both species will produce copious quantities of seed, suggesting that high infestation rates for both species may be a risk in irrigated crops.

Effect of seed burial on emergence, growth and persistence of wild oats and sterile oats

The seed longevity and emergence pattern of wild oat and sterile oat were monitored in field conditions at Gatton, Narrabri and St. George. Fresh weed seed was placed into nylon bags and buried at depths of 0, 2 and 10 cm in November 2017. Bags were exhumed at 6-month intervals over 30-months to evaluate seed germination, viability and decay.

For both species, 50 per cent of seeds at the surface and 10 cm depth had decayed within the first six months. Shallow burial (2 cm depth) of the seed increased persistence, with a significant percentage of seed being viable in the following winter cropping season.

The largest cohort of both species began to emerge at the start of the winter season (May). To ensure the seed bed is clean prior to planting, consider using tillage, herbicide application and cover crops to control this early cohort of Avena weeds. Tillage will bury seeds below their maximum depth of emergence and subsequent tillage should not be performed for 3–4 years to avoid bringing seeds back to the ‘emergence’ depth. Later emerging cohorts (through to October) will be suppressed using strong crop competition or a winter fallow if the infestation is severe.

The results of this research suggest that management strategies that can control all emerged seedlings over two years and restrict seed rain in the field could lead to complete control of weedy Avena spp. in the field.

Effect of wild oats and sterile oats infestation on wheat yield

The interference of wild oat and sterile oat in a wheat crop was examined through field studies in 2019 and 2020 at Gatton, Qld. Infestation levels of 0, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 plants m2 of both weed species were evaluated for their impact on wheat yield.

At an infestation level of 15 and 16 plants per m2 for wild oats and sterile oats respectively, wheat yield was halved as a result of reduced spike number per m2.

At the highest weed infestation level (48 plants per m2), wild oat and sterile oat produced a maximum of 4800 and 3970 seeds per m2, respectively. At wheat harvest, wild oat exhibited lower seed retention (17 to 39 per cent) than sterile oat (64 to 80 per cent), with most of the wild oat seeds having fallen from the seed heads before crop maturity.

The results of this study suggest that harvest weed seed control is likely to be a useful tactic in paddocks infested with sterile oat. An integrated weed management strategy that uses both chemical and nonchemical tactics is required to avoid severe crop yield loss, increased weed seed production and weed seedbank replenishment when these weed species are present.

This body of research highlights the benefits of an integrated weed management program that takes the ecology of the target weed into account.

Source: WeedSmart

This research was conducted by researchers from the University of Queensland, a WeedSmart scientific partner, with investment from the Grains Research and Development Corporation a WeedSmart sponsor.

HAVE YOUR SAY