INFRASTRUCTURE charges imposed on trucks and rail operators at ports have helped the stevedoring industry increase average revenue per container lift for the first time in seven years, according to the Container Stevedoring Monitoring report 2018/19 released this week by the Australian Consumer and Competition Commission (ACCC).

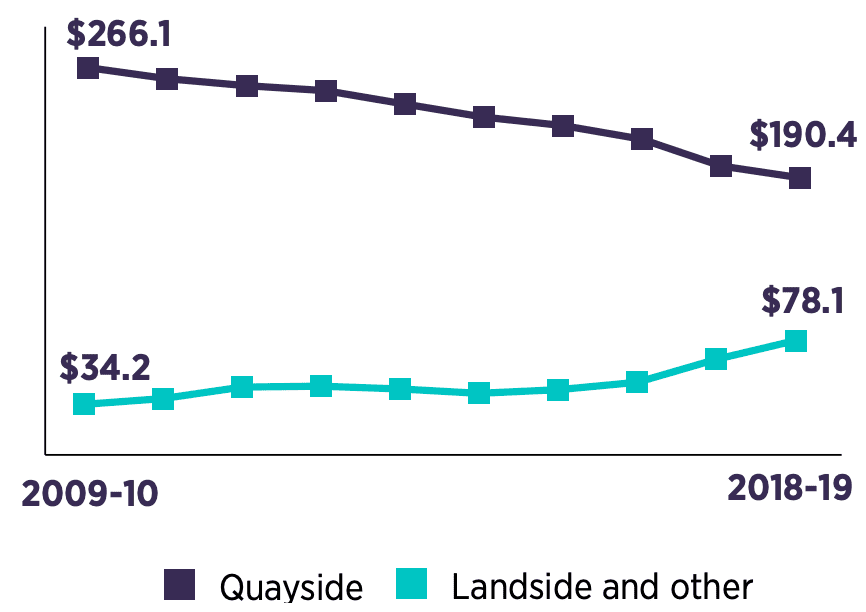

Average revenue per lift across both the quayside and landside increased by 1.8 per cent to $268 per lift (chart 1).

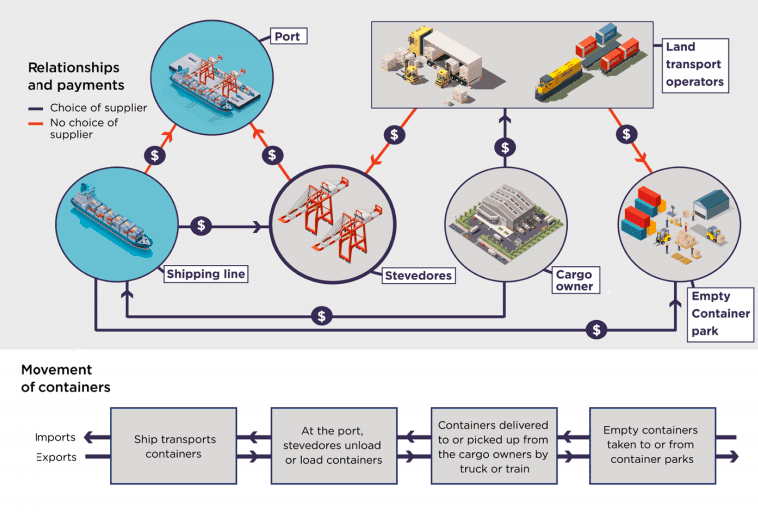

Container stevedoring involves lifting containers on and off ships, the costing comprising quayside charges and landside components. Over recent years stevedores have shifted costs onto landside operators, away from quayside, practically imposing higher charges on trucking operators who have less negotiating power than shipping companies.

Chart 1 shows stevedores revenue per container lift. Costs have been transferred onto those paying landside and away from those paying quayside (click to expand) Source: ACCC

The ACCC currently monitors the prices, costs and profits of container stevedores at five Australian container ports commenced in 1998-99 under a direction from the Australian Government.

Container port operators include Patrick and DP World at the four largest ports, Brisbane, Fremantle, Melbourne and Sydney.

Hutchison operates in Brisbane and Sydney, while new entrant Victorian International Container Terminal (VICT) commenced operations in Melbourne in 2017.

Flinders Adelaide is the sole terminal operator at Port Adelaide.

Port users will continue to be subject to increasing infrastructure charges, with Hutchison increasing its charges in Sydney in November 2019 and DP World increasing charges at all its terminals from January 2020.

An industry source told Grain Central that new infrastructure charges were imposing additional $50-100 per container, meaning up to an extra $4/t paid by exporters and importers, significant especially in respect of low value goods like most grains products.

“Transport operators are being charged to get access to port terminals with charges that include slot fees, container chain fees and infrastructure charges,” the source said.

“It is understandable that stevedores seek to recover some costs of upgrading port facilities from transport operators because they, like the shipping lines, benefit from the investment,” ACCC chair Rod Sims said.

“But because port users have limited ability to move their business in response to a stevedore raising its infrastructure charge, the stevedores face less competitive pressure to keep the charges down.

“While the infrastructure charges only represent 12 per cent of the stevedores’ revenues today, the outcome of this may be that importers and exporters end up paying more to ship goods.

Industry-wide profitability low

Profitability across the industry remains low with return on tangible assets falling from a high of 27.8pc in 2011-12 to 3.8pc in 2018-19, though it varied widely between stevedores. The lower return is partly due to the growth in the industry’s asset base after investment in new container terminals in the east coast ports.

The stevedores significantly improved their productivity on the quayside last financial year, with two key productivity measures, labour rate and ship rate, now at record levels.

“We found that the productivity of Australian container ports was generally on par with ports of a similar size overseas, with Melbourne the best performer.

“It is possible that our ports are not more productive because the distance between ports means competition between them is not very strong.”

Competition within ports led to further shifts in the market share of stevedores with DP World’s share of national lifts falling from 44.4pc to 39.1pc. Patrick picked up new business and its share of national lifts increased to 43.5pc.

New entrant Victorian International Container Terminal (VICT) has established itself as an effective competitor in Melbourne by more than doubling its share of lifts to around 15pc.

The use of infrastructure charges means that stevedores are earning a growing proportion of their revenues from customers that are more limited in being able to respond to those charges, in contrast to the competitive market in which stevedores provide services to shipping lines. The outcome of this may be that importers and exporters will pay higher charges to ship their goods than otherwise.

Bunkers up

A revised global shipping fuel emissions standard called IMO2020 will apply from 1 January 2020, expected to significantly increase the cost of shipping cargo.

Container shipping lines are required by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) to significantly limit sulphur emissions by switching to fuel with a sulphur content no higher than 0.5pc. This compares to the current cap of 3.5pc.

Industry expect the charge will be rolled into the existing BAF (bunkers adjustment factor) component of freight paid by shippers, usually calculated every quarter.

Source: ACCC

HAVE YOUR SAY