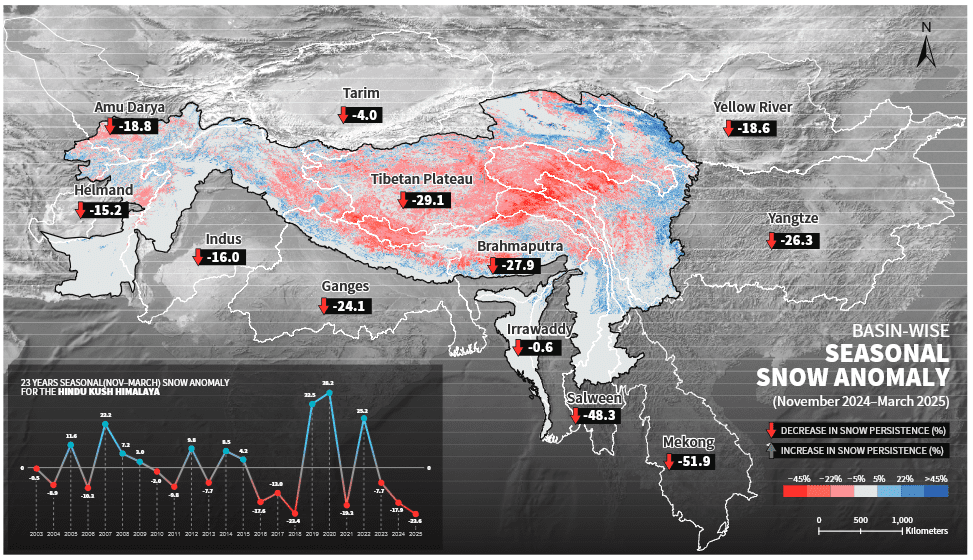

Figure 1: Snow cover persistence anomaly from November 2024 to March 2025 compared to the historic reference period from 2003 to 2024. The map shows the spatial distribution of snow persistence anomaly, and the overlaid graph is the HKH-WIDE average seasonal (November-March) anomaly since 2003. Source: ICIMOD

NESTLED high above Asia’s crowded plains and winding river systems, the Hindu Kush-Himalayan (HKH) mountain ranges have stood tall as guardians of life for eternity, their snow-covered peaks storing nature’s most precious resource: water. However, snow cover in the region plummeted to a record low in the winter of 2024-25, threatening water security in Asia’s major river basins and biodiversity across large swathes of the continent.

Making the situation even more alarming is the fact that this was the third consecutive winter that the region has received below-average snow persistence, the duration of time that snow remains on the ground in a given year.

The HKH mountain range stretches across eight countries on the Asian continent: Afghanistan; Bangladesh; Bhutan; China; India; Myanmar; Nepal, and Pakistan. These mountains hold the largest reserves of ice and snow, and the most glaciers outside the polar regions, earning the nickname Third Pole.

On average, snowmelt contributes around 25 percent of the total annual runoff of 12 major river systems in Asia. Therefore, anomalies in seasonal snow persistence have a dramatic impact on the water supply for the two billion people who reside in these river basins and depend on rivers and reservoirs fed by meltwater from the region’s snow-capped peaks. It’s an acceleration of a trend observed over the past quarter century, and the implications of this trend are enormous.

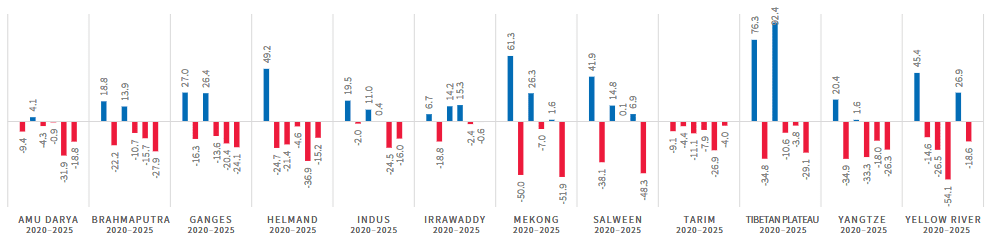

The river basins it supplies include the Amu Darya Basin which feeds rivers in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan; the Brahmaputra Basin which feeds rivers in China (Tibet), India, Bhutan, and Bangladesh; the Ganges Basin which feeds rivers in Nepal, India, and Bangladesh; the Helmand Basin which feeds rivers in Afghanistan and Iran; the Indus Basin which feeds rivers in China (Tibet), India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan; the Irrawaddy Basin which feeds rivers in China and Myanmar; the Mekong Basin which feeds rivers in China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam; the Salween Basin which feeds rivers in China, Myanmar, and Thailand; the Tarim Basin which feeds rivers in China’s Xinjiang region); the Tibetan Plateau which feeds rivers in China, and affects multiple basins like Indus, Mekong and Yangtze; the Yangtze Basin which feeds rivers in China; and the Yellow River Basin which also feeds rivers in China.

Figure 2: Snow persistence anomaly from 2020 to 2025 in major river basins o the HKH. Source: ICIMOD

The alarm has been raised by a recent report from the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), the regional mountain climate watchdog. The annual report provided an analysis of seasonal snow persistence for the November to March period.

The seasonal snowmelt is critical for regional water availability, especially the early melt, which flushes river systems for agriculture and hydroelectric power, and nourishes countless wetlands ahead of summer. Continuous deficits in water from snowmelt mean water volumes progressively decrease each year, with drinking water, food production, power generation, and the environment being the biggest casualties.

According to the report, below-normal snow persistence occurred 13 times between 2003 and 2025, but the growing concern is the increasing frequency and intensity of such occurrences in recent times. The 2024 update reported a decrease in snow persistence of 18.5pc compared to the mean snow persistence recorded in the preceding two decades. However, the most recent winter saw historically low snow persistence at 23.6pc under the 20-year average, the lowest recorded since the inception of the monitoring 23 years ago.

Recorded snow persistence was below normal across all 12 of the major river basins, with the most alarming decline observed in the Mekong, down 51.9pc, and Salween, down 48.3pc.

Also down were the Tibetan Plateau by 29.1pc, Brahmaputra by 27.9pc, Yangtze by 26.3pc, the Ganges by 24.1pc, the Yellow River by 18.6pc and the Helmand by 15.2pc.

Even snow-dominant basins such as the Amu Darya, down 18.8pc and Indusm down 16pc experienced alarming reductions in 2024-25.

While still negative, the least-affected basins last winter were the Tarim and Irrawaddy, down 4pc and -0.6pc respectively.

This will inevitably lead to lower and warmer river flows, increased groundwater extraction downstream, less soak to replenish artesian basins, and a heightened drought risk due to lower atmospheric water.

It could ultimately lead to catastrophic crop losses in coming years, jeopardising domestic and international food supply, and potentially make cross-border water-sharing arrangements, already extremely politically sensitive, a major flashpoint.

HAVE YOUR SAY