Converting cropping land to permanent pastures is one of the 13 accredited soil carbon sequestration practices. Photo: WA DPIRD

GROWERS should not expect payment will outweigh costs of sequestering soil carbon as part of the Clean Energy Regulator’s Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) program, according to a University of Western Australia (UWA).

UWA professor for Agricultural & Resource Economics, David Pannell, argued that the ERF program does not offer benefits to broadacre croppers or graziers and should be shut down.

Professor Pannell discussed these findings as part of the Australasian Agricultural & Resource Economics Society – Western Australia branch webinar.

The results were based on research paper Challenges in making soil-carbon sequestration a worthwhile policy, that Professor Pannell co-authored with High Performance Soils CRC CEO Michael Crawford and published in the Farm Policy Journal, Autumn 2022.

The paper looked into whether the ERF would provide financial gains for growers with either crops or pastures and if the program was a cost-effective method to reduce carbon emissions and combat climate change.

As part of the study, he looked at the 13 eligible practices for sequestering soil carbon, including:

- applying nutrients to the land;

- applying lime to remediate acid soils;

- applying gypsum to manage sodic soils;

- undertaking new irrigation;

- re-establishing or rejuvenating a pasture;

- switching from cropland to permanent pasture;

- grazing management for soil vegetation cover;

- retaining stubble after harvest;

- reduced or no tillage practices;

- controlled traffic, deep ripping, water ponding;

- clay delving , clay spreading, inversion tillage;

- using legumes in cropping or pastures; and

- cover crops to promote soil vegetation cover.

“The government considers soil carbon to be a significant part of its overall efforts to address climate change,” Professor Pannell said.

“A farmer might be tempted to think this could be an easy way to make some money, that all they need to do is measure their current level of soil carbon, adopt one of the 13 eligible practices and then measure the increase in soil carbon, tell the government about it and wait for the cheque.

“However, it is not quite as rosy potentially as that sounds.”

David Pannell

ERF program limitations

He said the program hit its first roadblock when it came to examining what actions contributed to increasing soil in carbon.

“The major drivers of carbon stocks in the soil are known to be rainfall and soil type.

“Management makes a difference, but it is a relatively minor contribution, and that is backed up by the fact that the measured gains in soil carbon in soils have mostly been pretty small.”

Professor Pannell said other challenges growers will face in carbon sequestration is that the measurable level reaches an equilibrium over time and that some adoptable practices actually work against the goal of the program.

“The level of new sequestration that is occurring year after year is actually falling over time.

“You don’t continue to get the same level of sequestration that we start with.

“There could also be as a side effect of the practices that the farmers adopt; that there could be other increases in emissions.

“For example, one of the key changes…is to switch from permanent cropping to permanent pasture.

“That is probably the change that would result in the largest in soil carbon.

“But on that permanent pasture, you would expect farmers to run livestock and from the livestock, you would have emissions of methane.”

He said in this example the carbon sequestered would be cancelled out by these new emissions.

“Even if farmers don’t switch to livestock production and increase their emissions that way, higher soil carbon under a crop enhances the conversion of nitrogen fertiliser to nitrous oxide gas and that is a concern because nitrous oxide is 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide per unit of gas.”

He said nitrous oxide levels also don’t decrease over time like soil-carbon levels.

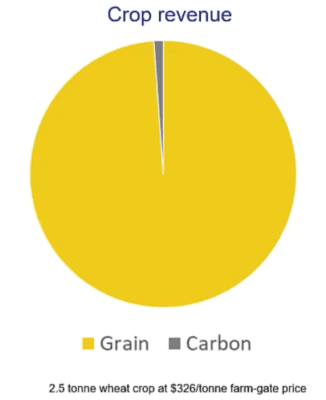

The estimated revenue from a 2.5t wheat crop at $326/t farm-grate price as a percentage of revenue from carbon sequestration payments. Source: David Pannell

Professor Pannell said soil-carbon sequestration can also reduce the level of nutrients available to plants, with farmers potentially required to add additional nutrients or accept a lower crop yield.

The other factors Professor Pannell considered in his findings included the tangible costs of implementing a practice, such as establishing a baseline, measuring soil-carbon levels (currently sitting at about $30 per hectare per year), and completing the paperwork.

With the program requiring growers to commit for long-term contracts, such as 25 years, this “inflexibility” would hinder participants from adopting new technologies or practices in the future.

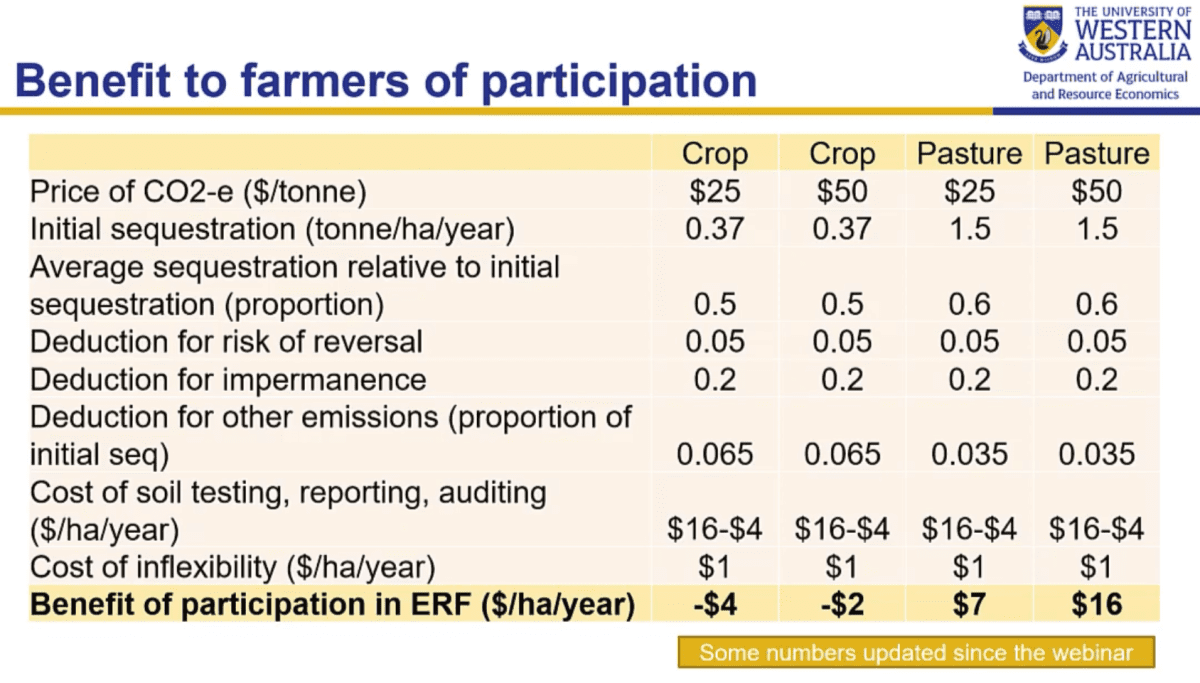

Professor Pannell estimated the potential payment a grower would see was $9/ha/year.

He then subtracted these potential cost factors, including reducing the soil to manage soil carbon levels to the amount touted by government by 2030 of $3/ha/year.

“Bringing that series of numbers together and doing the calculations, I end up with a benefit of participating in the ERF of minus $4/ha/year.

“Farmers are actually worse off if they join the program than if they don’t.

“If the price of carbon goes up to $50 and nothing else changes, of course the benefit to participation goes up a bit but not dramatically.

“Most farmers shouldn’t expect big money from the ERF for soil carbon, especially croppers.

“I have played around with those numbers quite extensively and I can’t really find a scenario that makes it look worthwhile for croppers to commit.”

The cost benefits to broadacre growers and pasture farmers from the ERF program. Source: David Pannell

Other benefits motivate change

Professor Pannell said he believed government should wind back the ERF program and instead focus on enhancing the private benefits growers will see from soil-carbon sequestration practices.

He said recent studies, including a UWA survey of farmers, showed that the program wasn’t motivating change and on-farm benefits, such as improved soil condition and quality, and more productive crops or pastures was the main factor in changing behaviours.

“My view is that the government should stop issuing contracts for soil carbon under the ERF.

“If it wishes to pursue a strategy for increasing soil carbon, there is really only one serious option that it could do, and that is to change tack and approach and invest instead in trials and extension about the relevant practices to facilitate farmers in adopting, motivated by private benefits.

“We know private benefits are going to be the main motivation, so let’s double down on that and try and make that the key driver and do things needed for that to work.”

He said other initiatives focused on reducing methane emissions from livestock, such as a program introduced in 2007 and later disbanded, would produce improved carbon reduction outcomes rather than concentrating solely on soil-carbon sequestration methods.

Grain Central: Get our free cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

If average sequestration relative to initial sequestration is 0.5 tonnes of carbon – doesn’t this amount have to be multiplied by 3.667 to provide tonnes of CO2 equivalent?

This will impact the Benefit of participation and it not be -ve.

Lots of good points from David here. The long contract timeframe for a project is hard to commit to with all the unknowns at this point in time. I think increasing soil carbon/microbe life has benefits all round. Would like to find a 5-year contract to get a feel on the process on 50 to 80ha. We have put a few summer crops in and have been impressed with how they compete with summer weeds. It would be great to know how much carbon they add to soil, compared to spraying all weeds leaving soil bare and dusty.

Finally some honesty about the monumental waste of money by Australian governments that is likely to get much worse.

Its largely promoted by self interested ‘entrepreneurs’ in business and science for their own needs

If the wider public were actually seeing the truth they would much less support the schemes that are worthless for anything but politics.

Ignorance rule.

well done David P