Not burning the chaff heaps does allow more weeds to persist but, as this photo with Ben Webb shows, the chaff cart does a good job of cleaning up the whole paddock and concentrating the weeds in a very small area.

FOR mixed farming operations like ‘Marbarrup’, west of Kojonup in Western Australia, there are a stack of good reasons not to light up chaff heaps — they are just too valuable.

Ben and Emily Webb farm 2150 arable hectares and run 4500 dual purpose Merinotech ewes and their offspring on crop stubble and 935 ha of non-arable pasture.

Their recent investment in a chaff cart to provide non-herbicide weed control also provides them with a valuable feed source over summer and better livestock production.

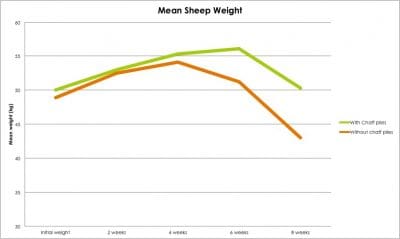

“In a trial that Ed Riggall at AgPro Management ran on our property in the summer of 2015–16 the sheep gained more weight when they had access to canola chaff heaps compared to grazing a similar paddock without chaff heaps,” Mr Webb said.

“The sheep grazed the canola for six weeks over December and January, gaining an extra 3.8 kilograms/head over the gains made by sheep just grazing stubble.”

The nutrient analysis of the canola chaff heaps showed the feed value was 7.3 per cent crude protein and 6.1 MJ/kg DM metabolisable energy.

Not only did the sheep gain additional weight, the Webbs also saved time and money on supplementary feed that would be required to achieve the same weight gain.

Mr Riggall calculated the benefit of grazing chaff heaps for a typical, model farm of 2000ha with 50pc crop and running 9.5 DSE/ha would be an average saving of over $29,000/annum and an internal rate of return on investment (ROI) on a chaff cart of 36pc per annum over 20 years.

This is averaged across livestock weight gains achieved on canola, barley, wheat and oats chaff heaps in a detrimentally wet season.

“In addition to this considerable benefit, we also saw a 25 per cent improvement in lambing percentage in the ewes grazing the canola heaps compared to those just grazing stubble,” Mr Webb said.

“This is a direct consequence of the higher productivity from heavier ewes in higher body condition.”

Mr Webb has found the sheep do a good job of knocking down the heaps, particularly when a large mob is given access to the paddock for a short time.

Prior to seeding grazed chaff heaps he often runs over them with a scarifier to spread the residue more evenly.

This makes it easier to seed through the heaps and reduces the need to burn in autumn.

“Ungrazed heaps definitely shed rainfall better but under the right conditions the grazed heaps still burn very well if we decide that’s the way to go,” he said.

“The sheep do best on the canola stubble so that is our priority for grazing. The canola heaps don’t generally need much done with them after grazing but I often burn the wheat, oat and some barley chaff heaps after grazing because they can be a pain to seed through.

“We have trialled narrow windrow burning here a few times but find that it is often too wet to achieve a good result. Moving to the chaff cart and grazing the heaps has been working better for us.”

Scientific studies have shown that sheep do not spread weed seeds as the seeds are destroyed as they pass through the sheep’s gut.

A study by CSIRO scientists in 2002 concluded that less than four per cent of annual ryegrass seeds consumed could survive passage through a sheep’s digestive system and similarly a 2010 international study showed both annual ryegrass and wild radish seeds were destroyed after two days in the rumen.

The Webbs use the chaff cart on all their cropping land and have seen a reduction in herbicide use across the whole farm.

In addition to harvest weed seed control with the chaff cart, the Webbs have also been including as many high biomass, competitive crops in their rotation as possible.

Their current program includes canola, barley, lupin and wheat, with trial paddocks of faba bean.

Mr Webb has found that growing RR and RT canola has provided excellent biomass production and allows them to restrict the use of clethodim to the lupin phase of the cropping program only.

Ben Webb says Hyola 600 RR canola (pictured) and RT canola provide a high biomass crop that competes well with weeds and produces high quality chaff heaps for the Webb’s Merinotech sheep.

Frost is a concern every year and the Webbs have been heavily impacted in the last few years. One of the greatest difficulties being the unpredictability of frosts – early one year and late another.

They sow Calingiri, a noodle wheat, and Trojan, a bread wheat as early as possible to minimise the risk of frost damage.

Annual ryegrass, brome grass and wild radish are the Webb’s top-three weed challenges and to-date the herbicide resistance status is low.

A ‘quick test’ performed last year indicated that resistance to clethodim was building and this was a significant motivator for the Webbs to invest in the chaff cart.

Prior to sowing, Mr Webb applies a double knock of glyphosate followed by paraquat mixed with a pre-emergent herbicide.

He applies in-crop herbicides as required and hand rogues any surviving wild radish plants.

To reduce seed set they also crop top lupins and spray glyphosate under the swathe when windrowing canola.

Mr Webb has also been trialling windrowing in wheat and barley, primarily as a harvest management tool that also has benefits for late frost avoidance and to reduce seed set in late germinating weeds.

On the rare occasions that weeds have got out of hand the Webbs have also used hay production as a way to reduce seed set and drive down weed numbers.

Planting on 229-millimetre (9 inch) row spacing and paired rows, Mr Webb opts for higher end seeding rates for all crops to maximise yield and competition with weeds.

Cutting the crop as low as possible and utilising the stubble as fodder makes planting on narrow rows easier to achieve.

For more information about managing herbicide resistance visit the Weedsmart website: www.weedsmart.org.au

HAVE YOUR SAY