FALL armyworm (FAW), which continues to threaten a range of crops across Australia, is proving difficult to control by established spraying techniques.

Melina Miles

It is just over a year since the exotic pest arrived in Australia through the Torres Strait. It initially established across northern Australia through the winter months, but since September has extended its spread into New South Wales, and was detected in Victoria in December.

Addressing GRDC Grains Research Updates, Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries principal entomologist, Melina Miles, said there had been a dramatic change recently in the frequency and intensity of fall armyworm infestations.

“Over the past two months we have seen FAW trap numbers come up quite dramatically. The winner is 2700 moths for a week on the Atherton Tablelands. That tells you what the level of pressure is,” she said.

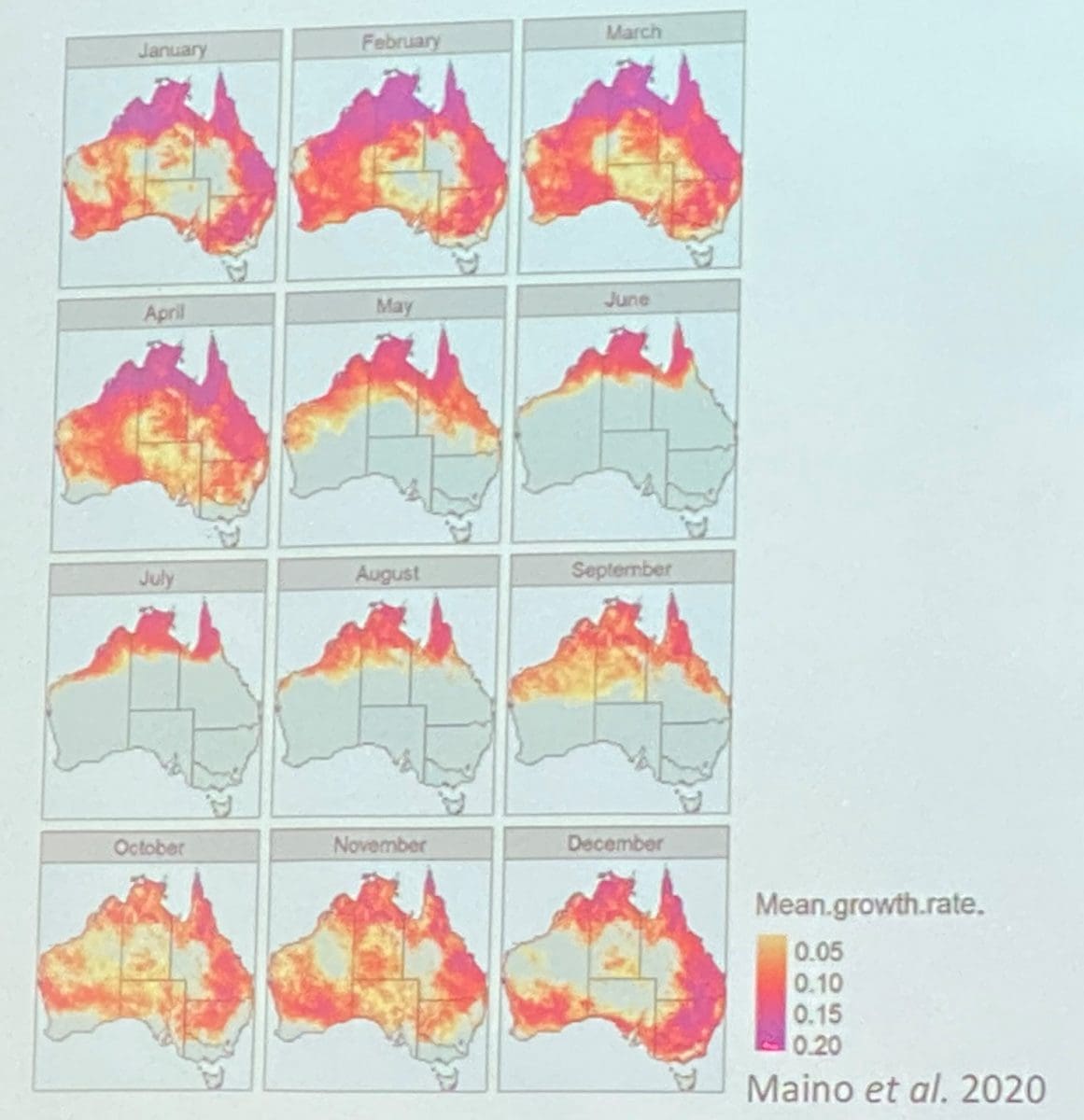

Dr Miles said while FAW had been widespread throughout Australia’s cropping regions over the summer months, she expected the tropical pest would contract to the northern regions during the cooler months.

Figure 1: Maps showing when and where conditions are suitable for fall armyworm to reproduce. The ‘hotter’ the colour the more suitable that area is.

Corn tops target list

Dr Miles said the current list of hosts targeted by FAW in Australia was relatively restricted, but contained some very important crops.

Maize for grain, popcorn and silage was the most favoured host, followed closely by sorghum, forage sorghum and sweet corn.

There have also been reports of FAW in Rhodes grass, peanuts, summer pulses and sugar cane – and even turmeric and ginger.

Dr Miles said she didn’t expect winter pulses such as chickpeas to be subject to attack from FAW because the pest was not very tolerant of cold weather.

“It is a tropical species and we expect it to contract from most of the chickpea areas before they can do much damage,” she said.

Control challenges

Dr Miles said FAW was proving very difficult to control with conventional spraying chemistry, particularly in crops like corn where the pests could often hide away from exposure to the chemical.

“The spray approach simply isn’t working for this pest. You can apply very effective insecticides and it does not die. What is going on? Is it about the very challenging location the larvae are in where you simply cannot get insecticide to them?” she said.

Immediately post crop emergence, small FAW larvae tend to spend the day just under the soil surface out of the sun and chew through the base of the plants.

Immediately post crop emergence, small FAW larvae tend to spend the day just under the soil surface out of the sun and chew through the base of the plants.

In more advanced crops they will hide in any nook and cranny. In corn, small larvae will enter the cob either through the top or by sitting under the wrapper leaves. When they are larger, they will bore into the side of the cob.

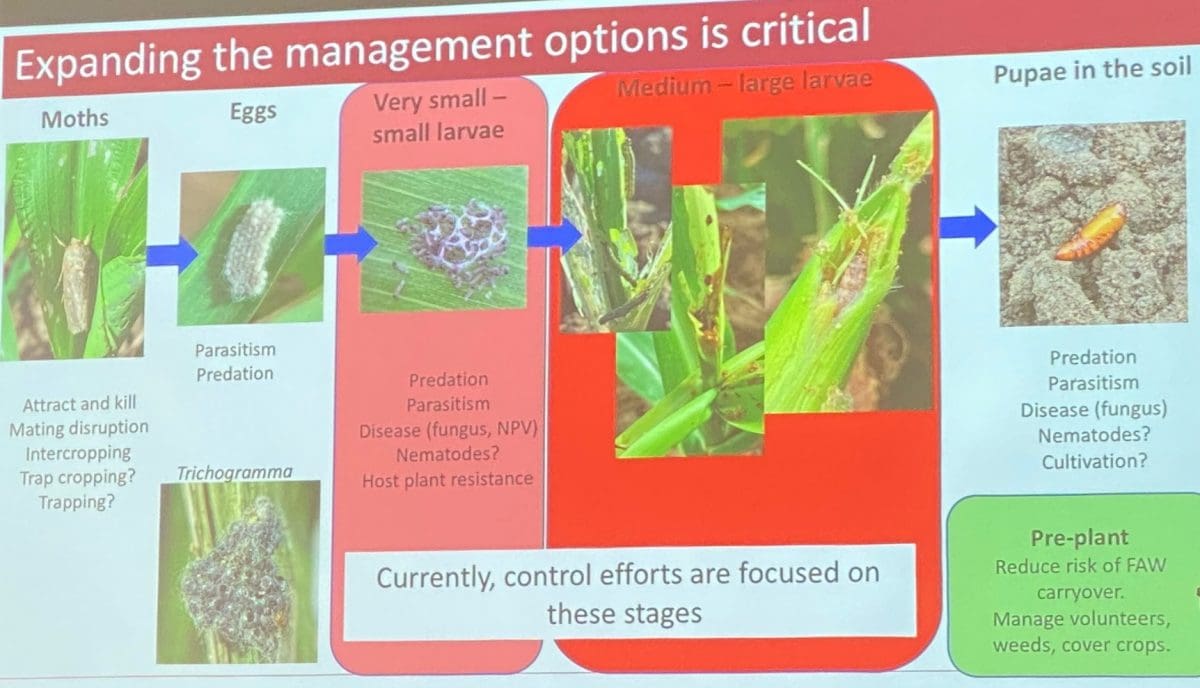

“We are looking at a change in the way we approach caterpillar management in crops from the ‘check, above threshold, spray, job done’ to something that looks more like population suppression,” Dr Miles said.

“To do that effectively, we need to add to the model of targeting the larvae. We need to look at how we might reduce the populations of ova-positing females, the survival of eggs and the survival of pupae.”

Biopesticide potential

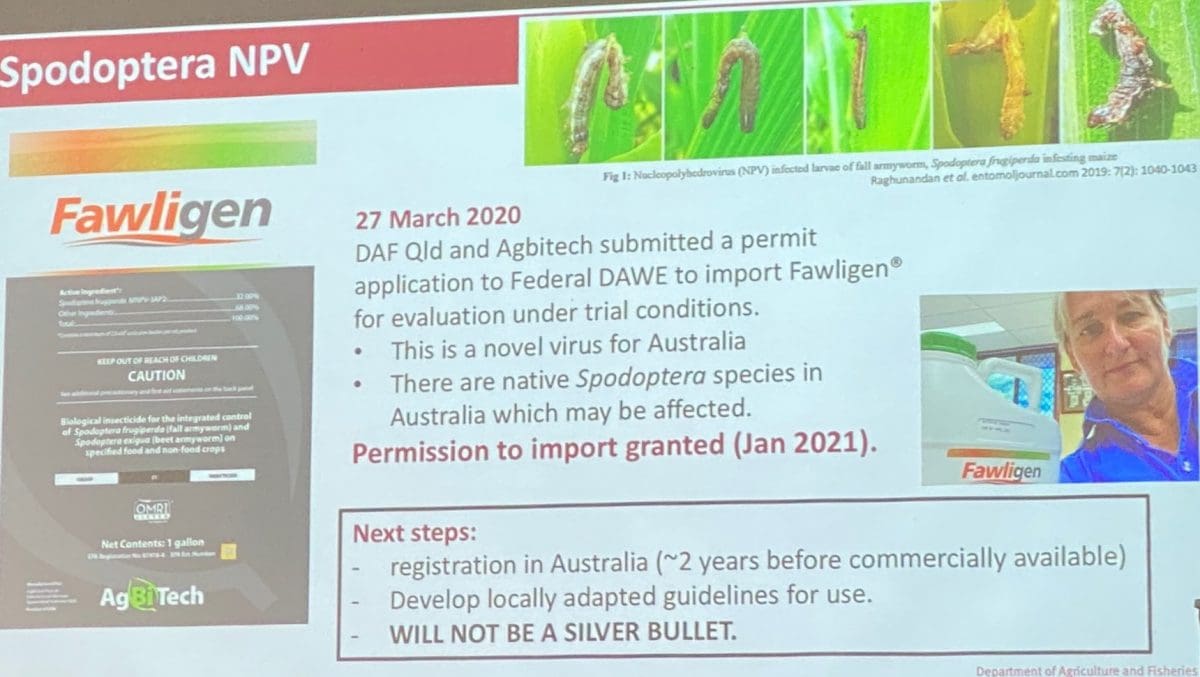

Dr Miles said one of the most exciting developments was that QDAF was granted approval in January to import the biopesticide, Fawligen, for evaluation purposes. It is now being trialled in north Queensland.

The biopesticide targets the FAW caterpillar which ingests virus particles, becomes infected and dies, spreading the virus to other FAW larvae in the crop.

“It won’t be a silver bullet. But it is exciting that the product has been allowed in,” she said.

Grain Central: Get our free cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY