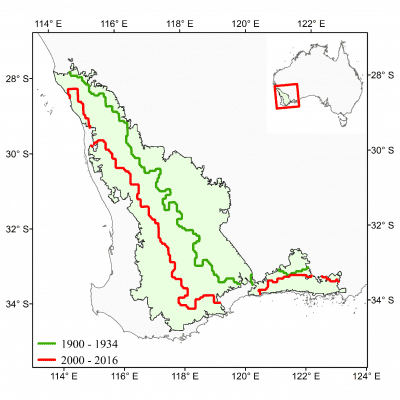

DESPITE a rainfall decrease in Western Australia’s wheatbelt between 1900 and 2016 which has shifted wheat yield potential south west by an average of 70 kilometres, actual wheat yields have remained unchanged.

Yield potential in the Western Australian wheatbelt has shifted on average 70km southwest from 1900 to 2016. Image: CSIRO

This was a key finding from Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, in new research published in Climatic Change.

CSIRO farming systems scientist Andrew Fletcher said the research highlighted the importance of research and development and the continued ability of farmers to innovate and adapt in order to keep farmers ahead of the curve.

“Given the changing climate, it seems likely there will be a decrease in wheat yield in Western Australia without continuous improvement in crop genetics and agronomic practice,” Dr Fletcher said.

The Western Australian wheatbelt covers about 60,000 square km and produces close to one quarter of the nation’s wheat crop.

Lived experience

Kellerberrin’s Kit Leake is a fourth-generation district wheat farmer who said his family was increasingly sowing its crops earlier in the season, and also dry sowing rather than waiting for autumn rain.

Kellerberrin farmer Kit Leake. Photo: GRDC

“It’s becoming more and more obvious that the climate is different now and we can’t keep on doing what we’ve always done,” Mr Leake said.

The impacts of climate change on cropping are especially pronounced in WA, as the state has undergone a significant shift in rainfall patterns.

This change is due to the southward movement of weather systems attributable to climate change.

Dr Fletcher said it was possible similar shifts in yield potential may have occurred in other parts of Australia and in other countries but to date, this kind of analysis had only been done for WA.

In the study, scientists analysed 117 years of daily climate data from 1900 to 2016 using the APSIM model developed by CSIRO and partners.

They combined climate data, including rainfall, with soil type to determine yield potential at numerous points across the WA wheat belt for each of the 117 years.

Yields stalled

CSIRO senior experimental scientist Chao Chen said the research was consistent with a 2017 CSIRO study showing national wheat yields had stalled since 1990, when they had previously been growing.

“Up until 2000, yields had been increasing but after that, they did not increase and year-to-year variation increased,” Dr Chen said.

While the overall yield potential in Western Australia shifted on average 70km to the Southwest, this is being offset by 35km due to increased CO2, which improves plant growth.

“Overall, the benefits of increased CO2 are far outweighed by a reduction in rainfall, the major limiting factor to crop growth.”

The researchers predict that in the future, the gap between yield potential and actual yields will close due to climate change as potential yields decrease.

Yield potential is defined as the yield farmers could achieve given climate and soil type and using best-practice and current technologies.

The research was supported by investment from the Grains Research and Development Corporation.

Source: CSIRO

HAVE YOUR SAY