THERE are certain things that come along and change the world – electricity, the Internet, mobile phones, and GPS to name just a recent few – and it’s very hard to imagine going back to living without them, even though people did for millennia. For farmers, conservation cropping changed the world – saving soil, water and bank balances along the way – and it is unthinkable to go back to full cultivation for weed control.

Glyphosate is so much more than a useful herbicide. It underpins the conservation farming system that has seen vast improvements in soil moisture retention and organic matter conservation, reduced wind and water erosion and has boosted crop yield and profitability.

The future use of glyphosate is under threat from two fronts – increasing herbicide resistance and increasing public concerns over its safety. In response to these threats Australian Herbicide Resistance Initiative (AHRI) researchers Hugh Beckie, Ken Flower and Michael Ashworth at the School of Agriculture and Environment, University of Western Australia, have outlined possible alternatives to glyphosate use and performed bioeconomic model scenarios for the control of annual ryegrass in southern Australian broadacre cropping systems without the herbicide.

What’s driving the push to ban glyphosate?

In 2015 the World Health Organisation International Agency for Research on Cancer classified glyphosate as a ‘probable carcinogen’ and in 2019 court cases in California tested this assertion, with the decision going in the plaintiff’s favour. Other significant agencies such as U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), continue to maintain that glyphosate-based herbicides are not likely to be carcinogenic and that the risk (hazard × exposure) of using glyphosate is acceptable when it is applied according to label instructions.

However, three studies published in reputable scientific journals in 2016 and 2019 all point to a link between glyphosate exposure and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. These studies and others could accelerate the restrictions and possible bans of glyphosate use, which has already begun in Austria, France, Germany and Vietnam. When a herbicide is not registered for use in a country, imported grain can be refused if residues of unregistered pesticides are detected. This will obviously have significant impacts on global trade, particularly for Australia where a large proportion of our grain production – wheat (65–75%), barley (65–70%); oilseed – canola (80%) and almost all of our pulse crop – is exported.

There are other herbicides, such as paraquat and diquat, that are also under heavy scrutiny. The potential loss of these three key non-selective herbicides would necessitate the development of new pre-seeding (including fallow) and pre-harvest weed control tactics.

Aside from regulatory decisions, the number of weed species resistant to glyphosate (and other herbicides) continues to increase, challenging the ongoing use of this key herbicide in no-till stubble retention cropping systems.

Either way, the Australian grain industry will need to adapt and develop new ways to manage weeds, which currently cost USD 2.3 billion each year in lost revenue and weed control costs.

On many Australian farms, early sowing and the use of pre-emergent herbicides and crop competition have negated the need for a pre-seeding knockdown such as glyphosate.

Maintaining low weed numbers without glyphosate

The loss of knockdown (fallow and pre-sowing) or pre-harvest (e.g. crop-topping) treatments, which may include glyphosate/paraquat/diquat, through resistance or regulation is expected to result in the following changes to current agronomic practices in southern Australia:

(1) an accelerated trend towards dry or early seeding, placing increased reliance on soil residual herbicides and crop competition;

(2) greater integration of pasture phases, with or without livestock grazing, in the cropping rotation;

(3) more, plus earlier, hay cutting (cutting the crop for fodder production before maturity for weed seed set control);

(4) greater attention to controlling weeds in fallow with selective pre-emergent or post-emergent herbicides, or strategic tillage;

(5) less production of inherently poor weed-competitive pulse crops, with greater attention to late season weed control via weed wiping or clipping above the crop canopy;

(6) a move to wider-spaced broadleaf crop rows and interrow tillage or shielded spraying; and

(7) greater use of pre-seeding or early post-seeding mechanical weed control, such as harrowing, rod-weeding or rotary hoeing.

What does bioeconomic modelling suggest for annual ryegrass?

Previous studies have suggested that global production of soybean, maize and canola will fall, and overall herbicide use will increase if glyphosate use is banned. The redundancy of the glyphosate-resistance trait in these crops (and others) could result in greater use of other herbicides. The loss of production will likely force the development of new land for cropping to compensate.

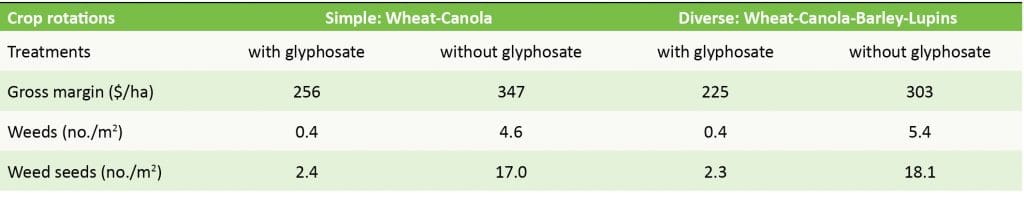

This AHRI research team ran the RIM (Ryegrass Integrated Management) model to assess annual ryegrass control, crop productivity and profitability with and without glyphosate. The study tested two cropping systems 1. A simple two-year wheat-canola rotation and 2. A diverse wheat-canola-barley-lupin rotation, across a 10-year span (see Table 1).

The results for these scenarios showed that ryegrass weed density and the residual seed bank would both increase markedly without glyphosate. When considering ryegrass alone, within the 10-year test period the increased weed pressure was not sufficient to negatively impact on gross margin.

Pre-emergent herbicides + high crop seeding rate + harvest weed seed control only partially compensated for the removal of fallow/pre-seeding and pre-harvest glyphosate applications.

Table 1 – Ryegrass Integrated Management (RIM) model scenarios (10-year span; southern Australia): simple or diverse no-tillage crop rotations with (control) and without glyphosate: management operations*, average annual gross margin (AUD $) and average annual residual weed and seed bank densities. See Lacoste for model details.

So, can we farm without glyphosate?

While the answer to this question is probably ‘yes’ for annual ryegrass, is it more likely to be ‘no’ when other weed species are considered.

This study suggests that if the only weed of importance on a farm is annual ryegrass, then transitioning to a no-glyphosate conservation farming system is possible and may not have a large economic impact within a 10-year timeframe. If other herbicides were also to be lost, then the economic outcome may be quite different.

This scenario has already been tested on many Australian farms and certainly can work for a weed like ryegrass, which is readily controlled through seed bank management. Where other weed species require control, particularly summer grasses, a much more integrated approach will be necessary if glyphosate was no longer an option, and a negative impact on profitability is highly likely.

Many farmers in Australia have already adopted integrated weed management programs that help reduce the pressure on herbicides – primarily in response to herbicide resistance in an increasing number of species and to a wide range of modes of action. The focus must remain on preventing weed seed set and diligently removing survivor weeds.

The development and adoption of more non-herbicide tactics will help preserve current herbicide efficacy and future-proof the Australian grains industry from regulatory impacts. Weed-competitive and early maturing cultivars, early terminating cover crops suited to knife-rolling, patch mapping and site-specific management, and high biomass / low disturbance systems such as the ‘strip and disc’ system are all options for further research and refinement. Region-specific research is required as some options/technologies are not suited everywhere.

Source: AHRI

Paper: Farming without glyphosate? by Hugh J. Beckie, Ken C. Flower and Michael B. Ashworth. Plants 2020, 9, 96; https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9010096

Grain Central: Get our free daily cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY