DRONE mapping is emerging as a potential tool for identifying mice activity in crops.

In a year when mice have been rampaging through cropping areas, particularly in the southern and eastern farming zones, farmers have been looking for ways to monitor and manage the damaging pests.

In a year when mice have been rampaging through cropping areas, particularly in the southern and eastern farming zones, farmers have been looking for ways to monitor and manage the damaging pests.

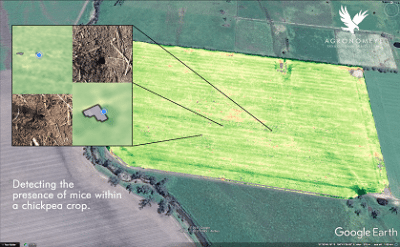

Agronomeye director, Stuart Adam, said he “stumbled across” the potential to add mouse mapping to the arsenal of data collected by his company’s aerial crop monitoring services when he was flying a drone over an early-stage chickpea crop at Blackville on the Liverpool Plains in northern NSW.

“Once we put in the soil filters and analysed the biomass that we had captured we noticed there were holes (gaps in the crop) in the data. We presented it to the client and his first reaction was “I bet they are mice”. We didn’t find mice as such, just the mice damage,” he said.

“We loaded the map into Google Earth on our phones and, with the client, walked out into the field and ground-truthed it. We looked down and there was mice activity everywhere.

“The mice were obviously in the crop and eating their way, like crop circles, out from their holes. As a result, there were holes in the crop. With the data we identified the holes in the crop and found the mice.”

Mr Adam said while the business was focussed on using fixed wing drones with multi-spectral sensors to determine crop variability from a wide range of causes, it was possible to identify variability caused by mice.

“We are not looking specifically for mice, but it is an add-on to the information we are providing to clients,” he said.

“We are trying to provide as much value as possible, whether through variable rate applications of fertiliser, identifying disease and pests.

“But it (mouse detection) could be done as a targeted data capture if that is what someone is looking for. It is horses for courses. We are not going out there specifically looking for mice, but if someone wants to do that we can achieve it.”

Mr Adam said his fixed wing drones could cover 600 hectares a day and deliver detailed, on the spot data and imagery.

“Because we are capturing data at four centimetres per pixel and then converting that data to a high resolution map at 30cm per pixel you get a lot of detail and can identify a number of variabilities, whether it be to do with plant health, soil variability or pests and diseases,” he said.

Potential outbreak next autumn

Meanwhile, CSIRO researcher Steve Henry said mice had been a problem over winter in many crops and spring monitoring of mice populations and potential conditions over summer had shown there was potential for the pests to be a problem again next autumn.

“One of the reasons we do a spring monitoring is to get a handle on how many mice have survived through the winter and when they started breeding in the spring,” he said.

“They are the two critical points in determining whether we should be concerned about an outbreak or damage the following autumn.

“If a large number of mice survive through the winter and they start breeding early, they are the real warning signs.

“We are concerned there is a moderate chance of an outbreak and potential for damage next autumn.”

Speaking in a podcast run by the Birchip Cropping Group (BCG), Mr Henry said the most challenging issue with mice was their rate of reproduction and increase.

“It almost means that by the time you have worked out they are there they have built to such numbers they are difficult to control. They really are reproductive machines. They start breeding at six weeks of age and have a litter of up to 10 pups every 20 days,” he said.

“Unlike other animals, as soon as they put the litter of pups into the nest they breed again. While they are feeding the young in the nest they are gestating the next litter.

“The conventional wisdom is that a single pair of mice can give rise to 500 mice in a season.

“When you get conditions favourable for breeding, there is no way natural predators can keep the populations in check.”

Control strategies

Mr Henry said farmers essentially had only one means of controlling mice: zinc phosphide spread at one kilogram/hectare, often as a coating on wheat.

“The frequency of baiting is really important. What you are trying to avoid is bait aversion. If a mouse gets a sub-lethal dose, it learns that is not a good thing to eat. So, we recommend that after harvest when there is quite a bit of food in the paddock, work hard to reduce the food potential,” he said.

Mr Henry said a key time for heading off the potential for mice outbreaks was in the lead up to sowing.

“At about six weeks before sowing, have a look in the paddocks. If you are concerned you have high mouse numbers at that point, do a bait application of 1kg/ha, remembering a mouse plague is characterised by 800 to 1000 mice per hectare,” he said.

“If you are spreading bait at 1kg/ha, that is about 22,000 lethal doses per hectare. If you find that isn’t effective, it is not because the mice have eaten the bait and haven’t died, it is because they haven’t eaten the bait at all, probably because there is an alternative food source.

“It is really important to try to spread the bait on as broad a scale as possible, particularly if there is a chance to co-ordinate a baiting program with your neighbours.

“If farmers have big numbers six weeks prior to sowing, go in and bait. If there are still quite a few mice just prior to sowing, at that point bait straight off the back of the seeder.”

Reduce food source

Mr Henry said another key to reducing the risk of mice outbreaks was to adopt good harvest hygiene practices and limit the amount of spilt grain.

“Keep the harvest as clean as possible, and keep the paddocks as clean as possible,” he said.

“For farmers who have sheep as part of their system, use the sheep in the stubbles to use up all the residual grain.

“Every time there is a germination, spray the germination out to reduce the amount of food that is in the system.”

HAVE YOUR SAY