Figure 1: Fall armyworm is proving difficult to control with conventional insecticides.

THE damaging exotic crop pest, fall armyworm (FAW), is proving difficult to control with conventional insecticides, prompting entomologists and agronomists to reach for a combination of suppression strategies that includes natural predators, mating disruption techniques and area-wide management.

The frequency of egg lays and the propensity of larvae to feed hidden behind wrapper leaves and in the whorl of host plants make chemical control only partially effective.

The familiar ‘check and spray’ approach isn’t working as effectively as it has with other insect pests.

To date the main crop targeted by fall armyworm has been corn, while there have been reports of activity in grain sorghum, forage sorghum, millet and summer pulses. So far there have been no recorded incursions in rice, sugar cane or cotton.

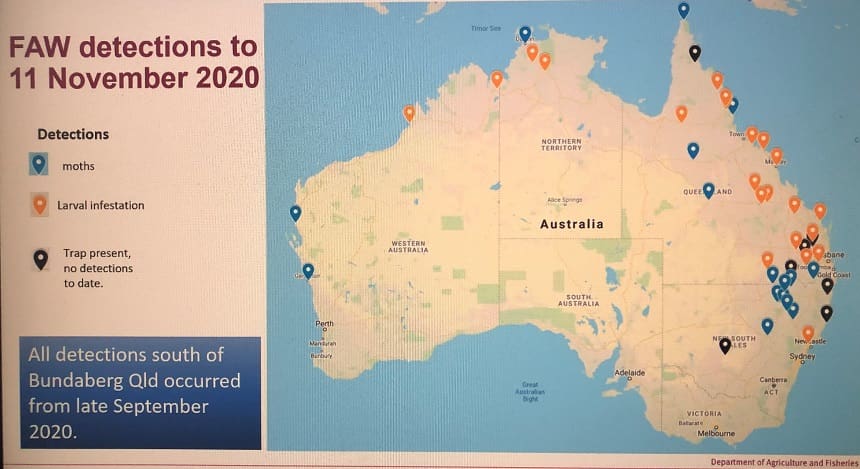

Marching southwards

Fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, arrived on mainland Australia through the Torres Strait islands in February and has since spread throughout Queensland and northern New South Wales, the Northern Territory and Western Australia.

The most southerly detections so far have been on a corn crop at Maitland in the NSW Hunter Valley, and moths at Gingin north of Perth in WA.

Figure 2: Fall armyworm detections.

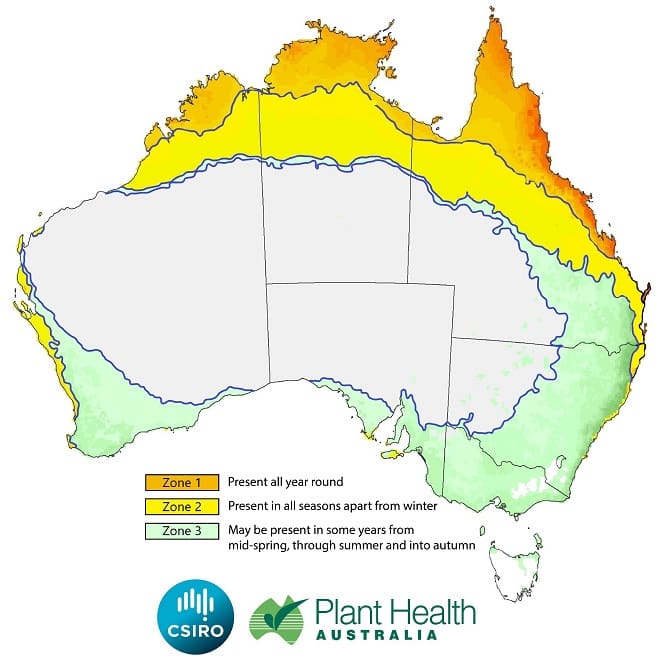

Addressing a GRDC Grains Research Update webinar yesterday, Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries senior entomologist, Dr Melina Miles, said there was potential for the pest to move to all parts of Australia, although it would not be as great a threat in the southern areas.

“It is a tropical and subtropical pest. It is not adapted to particularly cool conditions. So, moths that might turn up in corn crops on the Murray River on the Victorian border may do very well through December-February, but beyond that they will be constrained by temperature,” she said.

“Those more southerly incursions will die out over winter because the conditions will simply be too cold. Unlike Helicoverpa which have the capacity to rest in the soil over winter in a diapause phase, there is no diapause phase for fall armyworm.”

Alternative strategies

Dr Miles said the inability to control fall armyworm with conventional chemistries was a major risk to the cropping industry.

“It is really important to think about how we reduce our reliance on conventional chemistry. That will be key to the long term ability to manage not only fall armyworm but Helicoverpa,” she said.

“The only way that will be achieved is by employing more of the available tools that are not conventional chemicals and developing new ones to fit the system.”

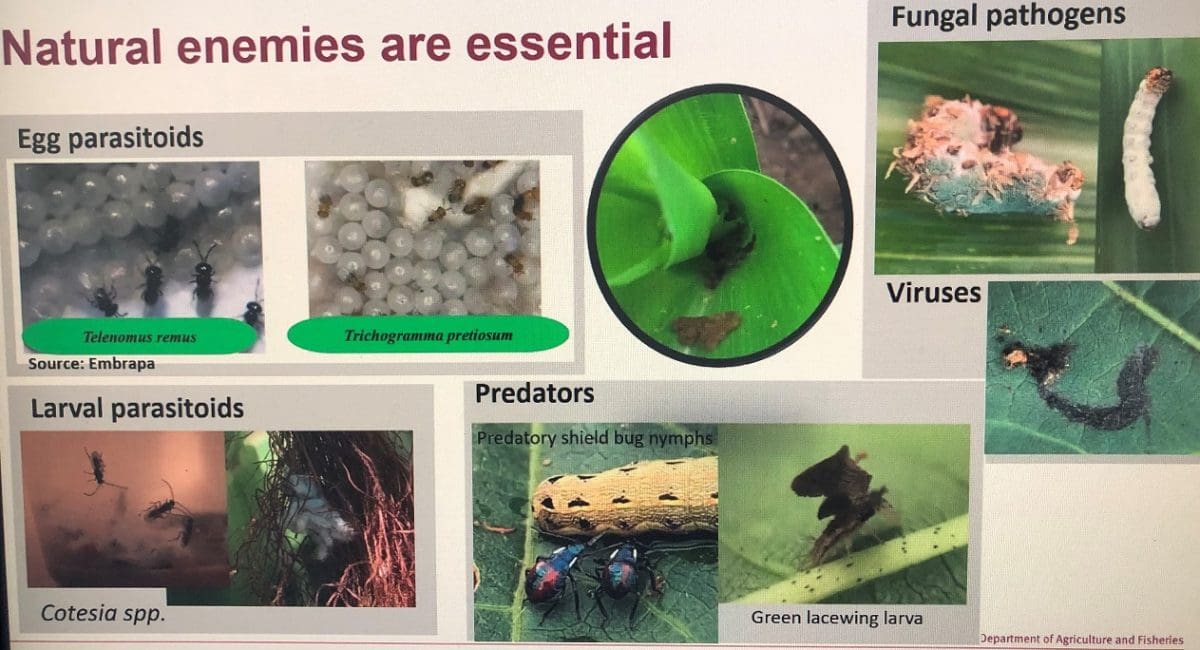

Dr Miles said the greater use of natural enemies was going to be an essential part of controlling fall armyworm, with tiny predators and parasitoids having a much better chance of getting to the pest hidden in the plants than insecticides.

“Egg parasitoids and larval parasitoids are very important because they stop the fall armyworm before it gets to the stage where they really do a lot of feeding damage,” she said.

“In my opinion, the system needs to be biased towards favouring the activity of parasitoids in particular.”

The strategy seeks to harness the use of predators such as shield bugs, green lacewing larva, fungal pathogens and viruses.

Figure 3: Fall armyworm’s natural predators.

Other measures include:

- ‘Attract and kill’ approach that takes a portion of the females out of the population by attracting them to feed on a product laced with a toxicant so the moths die.

- Strategic natural enemy releases, whether they are egg or larval parasitoids.

- Host plant resistance. Plants that have traits that are less susceptible to damage.

- Mating disruption with pheromones to prevent the females in the population maturing and laying their full complement of eggs.

- Trap crops.

- Area-wide management where growers come together and strategically determine for their district how they use insecticides and deploy trap crops for maximum effect.

Identification key to control

Also addressing the webinar, Nutrien Ag Solutions senior agronomist in the Burdekin region of north Queensland, Brent Wilson, said early detection and the ability to identify fall armyworm from similar looking pests such as Helicoverpa armidgera were key to its control.

Fall armyworm up to the third instar stage are hard to distinguish from Helicoverpa armidgera.

One of the indicators of fall armyworm is a window edging effect on the leaves of individual plants which isn’t typically seen with Helicoverpa.

Egg masses can be quite large, anywhere from 50 to 200 eggs (Figure 4). Unlike with Helicoverpa where egg laying is even, fall armyworm eggs are laid in clumps on the underside of leaves and are typically hard to find.

Figure 4: Egg masses can be quite large, anywhere from 50 to 200 eggs.

In the early hatchling stage typically they will have pink colouring with a large, black head. As they grow, typically they develop light green colouration (Figure 5). Colours can vary from dark, black, charcoal to brown, green.

The larvae of fall armyworm are typically found well entrenched within the whorl of a plant.

Figure 5: In the early hatchling stage FAW will have pink colouring with a large, black head. As they grow, they develop light green coloration.

New national plan

The ‘Fall Armyworm Continuity Plan’ is a new document that contains information about fall armyworm and its management in grain crops for Australian consultants and other industry professionals.

Produced with investment from the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC), it has been compiled by sustainable agriculture research organisation cesar, Plant Health Australia, the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International, and the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

Cesar research lead, Olivia Reynolds, said the national plan would be an important resource to aid industry in dealing with the exotic pest at this early incursion stage.

“It is intended as a reference document for professionals, specialists and consultants in preparing more localised and industry-specific communication and extension material,” Dr Reynolds said.

“This plan compiles information from international literature and expertise and provides a solid background of knowledge on the pest, which will support the development of effective management strategies, plans and information sharing networks.”

GRDC biosecurity manager Jeevan Khurana said the plan captured the global experience and used that to inform and anticipate what the industry faced in Australia and how best to manage it.

“Overall, there is a lot of activity occurring in Australia to ensure an effective response to fall armyworm – across industry, state and federal governments and the private sector,” he said.

“It will take time to adjust and learn how to manage this pest, and the central objective of ongoing GRDC investment in FAW is to help develop robust and sustainable integrated pest management strategies.”

Figure 6: The Fall Armyworm Continuity Plan maps out zones likely to be at risk from fall armyworm.

More information about FAW is available on the GRDC FAW portal and a detailed article about the FAW Continuity Plan is available on GRDC GroundCover online.

GRDC Paper: ‘Fall armyworm: What threat does it pose, and what tools do we have to manage it?‘

Growers are encouraged to monitor crops to identify signs of infestation early. If you suspect FAW, report immediately to the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline on 1800 084 881.

Grain Central: Get our free cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY