AN increasing number of no-till farmers are reverting to an occasional, strategic tillage as the most cost-effective way of controlling hard-to-kill weeds in an era when herbicide resistance is on the rise.

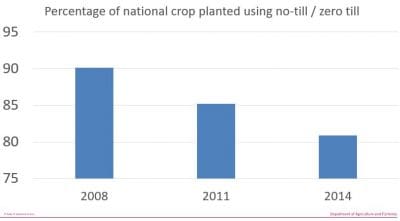

No-till farming peaked in the mid-2000s with about 93 per cent of the Australian crop sown under no-till farming regimes.

Since then, Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) farm practices reports have shown that no-till has declined by about 5pc a year from 2006 to 2014.

In line with that, the CSIRO found that about 25pc of broadacre farmers used some form of tillage last year and that of those 71pc had used it to control weeds.

So, why are growers turning to a one-off tillage event rather than maintaining their use of herbicides?

Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (QDAF) agricultural economist, James Hagan, Toowoomba, said far from abandoning their adoption of no-till principles, farmers were opting to make a short-term compromise by using strategic tillage as the cheapest, most effective way to control problem weeds.

“We are not seeing a complete reversion to tillage. What we are seeing is a one-off tillage, then once the weeds are under control they go back to a no-till system,” he said.

“Farmers are prepared to compromise on no-till for a one-off tillage that is more successful and more economic.

“Economics is the main driver. I don’t think it is being driven by agronomics because seeding and establishment can be compromised. The pure difference in cost and the effectiveness of control are what are driving the move to one-off tillage.”

Mr Hagan said research had shown it was far more cost-effective to apply an occasional tillage to control a heavy weed burden than run a herbicide program, even if the plants were not resistant to herbicides.

“Even if tillage is costing you $200 to $300/hectare, compared to the cost of yearly herbicide treatments, the tillage gives you good control whereas if you are relying on herbicide you might be doing eight sprays a year to clean it up over four to five years. It very quickly adds up compared to a one-off tillage event,” he said.

Grain Central: Get our free daily cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

Mr Hagan said it was the length of time that it took to bring a heavy weed infestation under control under a spraying regime that made it much costlier than tillage.

He pointed to research in Western Australia which showed the challenge of controlling a weed such as wild radish with herbicides alone.

“The trial data from 1999 to 2008 showed wild radish in WA used to be controlled with Group B chemistry using Logran or Glean. It was really cheap to control wild radish with Glean,” he said.

“But when weed numbers were really high, even with an effective chemical we got survivors and we weren’t able to get control using it.

“The best control when starting with high weed pressure relied on that Group B chemistry, but even after two years they still dropped out of crop production into a pasture to regain control. Under the worst control in the trials, they dropped it out of crop production into two years of pasture and did a tillage event, after weed numbers more than doubled in the first year.”

Mr Hagan said in eastern Australia in the northern farming zone of Queensland and NSW, certain weeds, such as feathertop Rhodes grass, had become particularly well adapted to no-till farming systems.

But it was that adaption to growing in undisturbed soils that made those weeds particularly vulnerable to being eliminated by tillage.

“A lot of them can’t emerge when buried at a depth of two centimetres or greater. So, when we have a weed that is not suited to emergence from two centimetres and is really herbicide resistant, it gives us a strong indication that tillage is the way to go,” he said.

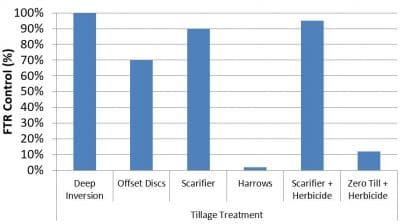

Mr Hagan said the case supporting strategic tillage was graphically illustrated in a trial in Central Queensland (Figure 2) which showed ‘no-till plus herbicide’ gave only minimal weed control while ‘scarifying plus herbicide’ gave 95pc control.

“That is not full inversion. It’s just because none of these weeds can emerge from 2cm that enhances control dramatically,” he said.

Figure 2: Central Queensland trial. Feathertop Rhodes grass control using different tillage treatments.

In WA, Mr Hagan said full inversion was the more common practice because of the different soil type.

“It is due to the non-wetting sands, so burying them is of benefit. Plus, if you can get 100pc weed control of wild radish or ryegrass, that is a benefit. Often they are liming or putting a nutrient on top and inverting that as well, getting it to depth,” he said.

HAVE YOUR SAY