WITH next to no winter crop planted in southern Queensland and northern New South Wales, tens of thousands of hectares of fallow sits ready for sorghum if soaking rain falls between now and January.

Sorghum fallow paddock in the New South Wales ‘golden triangle’ August 2018. Photo: Anthony Furse. Click to enlarge.

However, with subsoil moisture in many paddocks at less than half of what is required to grow a crop, researchers like the University of Southern Queensland’s David Freebairn and agronomists like AMPS’ Tony Lockrey at Moree warn that planting on a little rain and hoping for a lot could be a dangerous move.

“Discipline is the biggest word at the moment,” Mr Lockrey said, after some NSW and Queensland growers received up to 50 millimetres of rain last month, and up to 70mm in places.

“Knowing we don’t have full profiles, and that banks like us to harvest as many crops as we plant, means most growers are going to have to wait for another rain if they want to grow a decent crop.”

Mr Lockrey said a further 50mm at least was needed to shore up prospects for the 2018-19 summer crop, but some limited early planting of corn, sunflowers and forage sorghum was taking place.

If light rain forecast for today (Friday) falls in Moree and surrounds, Mr Lockrey said it may be enough to start the planting of grain sorghum next week, but most growers were holding off for follow-up rain and a rise in soil temperatures.

“We are still urging our growers to be judicious and discerning in their risk management for this coming summer and the opportunities it may or may not present.

“It could be a big summer crop, but it won’t be if we don’t get sufficient opening rain to be confident to commit to spending the coin needed to establish it.

“If we get sporadic rainfall up until Christmas, our best performing summer crop may be wheat planted next April.

“Let’s hope that’s not the case on at least 20-30 per cent of our country – some cash flow would be nice.”

Plenty of fallow

Dalby Rural Supplies director Andrew Johnston said high prices were encouraging growers to plan large-scale plantings of sorghum and cotton ahead of lesser water users like mungbeans.

“With the sorghum price at $380-$390 per tonne, it’ll be a huge planting of sorghum if we get the rain from now, and for the back end of October and into November for cotton.”

“It’s got the potential to be the biggest season we’ve ever seen for sorghum, but we’ve had no rain here to speak of, and we’ll need 50-75mm or maybe even 100mm to plant on.”

“It’ll all be sorghum and cotton first, and mungbeans from Christmas.”

Mr Johnston said southern Queensland’s predominantly winter-crop areas including Condamine, Meandarra and Surat have very little crop in the ground at present.

“The potential for a massive sorghum crop on the Darling Downs and in those areas west of us is certainly there.”

“We’ve got a lot of fallow, and a big window out to the end of January, so that gives us potential for sorghum plantings to be massive.”

Even on the typically high-yielding Liverpool Plains of NSW, very little winter crop was planted, and even less will be harvested following minimal rain in recent months.

Pursehouse Rural agronomist, Ben Leys, Quirindi, said growers on the Liverpool Plains were hoping for 150-200mm of rain to fill the profile for a 2018-planted summer crop.

“Our cotton planting window is open until the end of October, and we can plant sorghum to the end of December, but we’re a long way off planting anything at the moment.”

“You can’t afford to plant a summer crop when the forecast doesn’t look promising, and you’d just be chewing up subsoil moisture next year’s winter crop could use.”

Mr Leys said even paddocks where the last crop harvested was cotton in 2017 would need significant rain to ensure reasonable yields from a summer crop.

“Some country that’s been long fallowed still has less than half a profile.

“Prospects for dryland cotton are pretty slim; you’d want a lot of rain, and soon, to get a cotton crop in, but if we get a lot of rain by mid-October, it’d be one of the biggest sorghum crops around.”

If general and soaking rain has not fallen by late December, Mr Leys said he expected growers would look at planting mungbeans and sunflowers in January.

Gauging soil water

Dr Freebairn said growers tossing up options about what summer crop they should plant, or if they should fallow over the summer months, could look at the CliMate app to help them put some objective odds into decision-making with 10 analyses.

They include How’s the season?, which allows users to quickly explore the current season’s rainfall, temperature and heat sums, and is available from the Queensland Government’s Silo service for more than 3000 sites across Australia.

Looking forward, Dr Freebairn said the How often? analysis can help determine the chances of a summer-crop planting rain based on climatology, or long-term statistics.

“An example could be the chances of 50mm over a week for September/October, which is a lot of rain but given the current dry, what might be needed to get a viable establishment on heavy soils, while lowering the rain needed to 35mm only increases the odds from 38pc to 46pc, still a fair gamble.

“We have good climate records available and CliMate gives us ready access to them to add some objectivity to risk assessment.

“It’s in seasons like this that the importance of stored soil water comes to the front, assuming you got a planting rain.

“We generally have a good idea of how full a soil profile is in two conditions: when it’s bone dry and cracked or crops have died; and when we are bogged and the creeks are running.

“At other times, it’s generally more of a guess.”

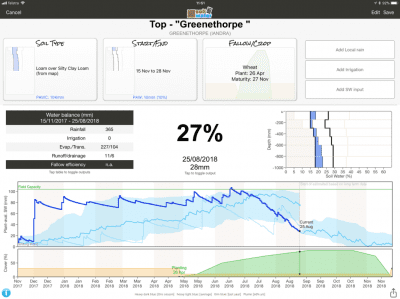

Dr Freebairn said the advent of handheld mobile devices has facilitated the bringing together of complex models and data in the SoilWaterApp (SWApp), which helps estimate plant-available soil water over time.

“This pulls together information about climate, soils and crops in a simple interface to provide a robust estimate of soil water status that can be used when and where decisions are made.”

“It provides an estimate of today’s soil water along with past and future projections for any specified soil type and simple fallow/crop sequence.

Each paddock is considered separately, and is linked to the nearest Bureau of Meteorology climate station, and local rainfall data can also be added.

A SoilWater app display for a wheat crop at Greenethorpe in NSW.

Output from the app quickly indicates a paddocks water status compared with last year, and the average, while providing a forward estimate.

SWApp was developed with funds from the Grains Research and Development Corporation and the Australian Governments’ National Landcare Program, and can be downloaded for free at the App Store by searching for “soilwater”.

Stored importance

Dr Freebairn said the importance of stored soil water has been obvious in a season like this one, with little in-crop rain to follow planting rain for those that were lucky enough to get it.

“Fallow dependency considers how reliant a crop is on water accumulated during the fallow period and consumed during the cropping phase, and it shows how important the soil is in buffering a crop in our unreliable rainfall environment.”

Rates of fallow efficiency and dependency differ between locations and cropping seasons.

Average rainfall, fallow efficiency and fallow dependency for four locations in eastern Australia

| Location and cropping season | Fallow efficiency percentage | Fallow dependency percentage |

| Emerald, winter crop (AAR 645) | 25 | 82 |

| Emerald, summer crop (AAR 645) | 22 | 26 |

| Dalby, winter crop (AAR 640) | 24 | 62 |

| Dalby, summer crop (AAR 640) | 26 | 27 |

| Moree, summer crop (AAR 525) | 28 | 32 |

| Moree, winter crop (AAR 525) | 18 | 36 |

| Walpeup (Vic), winter crop (AAR 340) | 9 | 11 |

Table: Fallow efficiency shows gain in stored soil water over the fallow period/fallow rainfall) x 100; fallow dependency shows change in fallow soil water storage/crop transpiration) x 100.

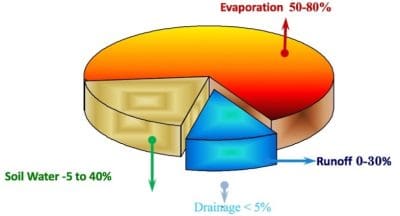

Dr Freebairn said evaporation is the greatest robber of rainfall during fallow, which typically begins at harvest or at the end of grain fill.

“Evaporation takes most of the small falls that wet up to 20cm below the surface, while weeds directly reduce the soil water from the surface and deeper soil layers and reduce nitrate accumulation.

“Both reduce yield potential next season.”

Typical fallow water balance for northern NSW- southern Queensland grain crops.

Dr Freebairn said a lower fallow dependency did not mean soil water at sowing was not valuable.

“It means that in a greater number of seasons you can get away with less soil water at sowing compared to places with high dependency, but the real test comes in years like 2018 when water is in short supply.”

“Knowing how dependent your crops are on fallow moisture for the next crop doesn’t guarantee an above-average yield, but it does emphasise the importance of storing moisture during winter and summer fallow periods.”

Australia’s commodity forecaster, ABARES, will release its initial estimate of Australia’s upcoming summer crop in its next crop report due out on Tuesday.

In its most recent June crop report, ABARES estimates Australia’s 2018 sorghum harvest at 1.4 million tonnes from 531,000ha, up from 994,000t harvested from 368,00ha in 2017, which was below the 2016 crop of 1.8Mt crop from 521,000ha.

HAVE YOUR SAY