AUSTRALIA’s 2018 winter crop was a tale of two halves with Western Australia producing a near-record crop, while the eastern seaboard suffered the ravages of a crippling drought in many areas that saw tonnages well down on average.

For growers in the West it was a year to remember; for many in the East it was a year to forget.

Wrapping up the season past, Grain Central takes a state-by-state look at ‘the winter crop that was’ in 2018 and the lessons that can be taken from it.

Western Australia

The Grain Industry Association of Western Australia (GIWA), in its December crop report, conservatively estimated the state was on track to produce at least 16.798 million tonnes (Mt) from the 2018 winter crop.

Since then, as the last of the harvest winds up, crops have been coming in better than expected, pushing beyond the projections to be not far short of the record 2016 harvest of 18.158Mt.

GIWA Oilseeds Council chair, Michael Lamond, said it had been “an amazing year” for winter crop production in WA.

“We had an unprecedented area of crop sown dry, with some estimates up to 80 per cent. Then we had a general break across the state at the end of May,” he said.

“The next two months were the most ideal growing conditions you could have asked for, except for the south coast and Esperance area. By mid-August it looked like we were going to have a record crop.”

But then the rainfall tap turned off during September and, coupled with severe frost events, prospects went from a potential record to some estimates downgrading the likely crop to below 12Mt.

“Then, we had rain just in the nick of time in early October in the central areas which really helped the wheat and arrested the slide we were experiencing in grain yield,” Mr Lamond said.

“Mild, cool conditions and a lack of hot wind in September/October meant the north finished beautifully. When it came to harvest, the crops were back to nearly what they looked like earlier on.

“As you move south, in the west Kwinana Zone it turned out a record crop. The eastern areas got out of jail with rain in October which didn’t really help the barley, but helped the wheat. There are good tonnages there.

“As you move further south, the Esperance Zone was wet on the coast and dry in the north and is on track to exceed expectations. Around Albany they didn’t get the waterlogging, so they had very good yields as well.”

Mr Lamond said the cool finish meant that even in the poor areas of the state, instead of getting nothing or only 0.5 tonnes/hectare ended up with 1.0t/ha which allowed many growers to break even.

“The only thing was the very good growing conditions meant everyone ran out of fertiliser. In the western areas where there is reasonably high rainfall it meant grain quality was really good, but as you go further east it is really erratic because people took a risk-averse approach from early August by not fertilising. The protein levels have been really low in some areas,” he said.

South Australia

In SA, which produced a record 9Mt in 2016 and 5.66Mt in 2017, a dry 2018 season meant grain handler Viterra at the end of December had taken in only 3.758Mt from the current harvest.

Former Grain Producers South Australia director and Mid North farmer, Stephen Ball, said the bulk of the state had had a very dry winter cropping season with well below average rainfall.

“There were some areas that had good rainfall such as the lower Eyre Peninsula and the South East. The rest of the state was very varied with a lot of dry areas and poor crops,” he said.

“On top of that, we had a huge frost event that wiped out sizeable areas of crop which were then cut for hay. The upside was it was a good year for hay with people paying good money for wheat and canola hay. There was a market for those frosted crops.”

Mr Ball said crop success was largely dependent on location and whether the previous crop had used up all the soil moisture.

“If there was carryover moisture that certainly helped. Soil type was also a factor. Traditionally the good soils, which are the heavier soils, yielded a lot less,” he said.

“On my farm at Riverton we had half our growing season rainfall. Ironically, harvest was delayed by wet weather in November and December.”

Victoria

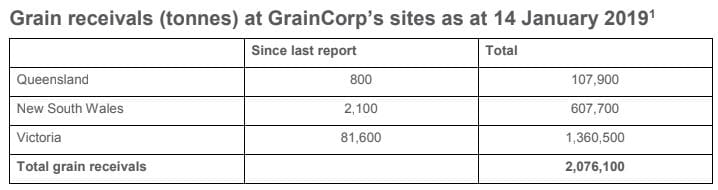

As the last of the harvest comes off in Victoria, GrainCorp receivals for the state have tallied 1.36Mt to date and will fall well short of the 3.739Mt it took in from the 2016 crop and 2.94Mt from 2017.

Robert Smith and Co director/agronomist, Andrew Golder, Warracknabeal, said production in the southern Mallee/northern Wimmera was down after a very low rainfall year.

“We were well below average across the board. Most of the crop went in, but not all of it was harvested. There was more hay cut than usual,” he said.

“We were on the border line here. North of Warracknabeal was pretty ordinary, south at least had something.”

Mr Golder said the lentil area was back slightly, probably because of price, and a reasonable area of canola went in, but most of it ended up being cut for hay.

“It was a really tough September, but we were lucky we didn’t get any warm weather in October. Grain quality was good considering the rainfall and we were lucky there wasn’t a hot day in October that would have shrivelled it up,” he said.

“We had 100 to 125 millimetres in late December that has set us up for next year.”

Farm 360 and Agronomise consultant, Simon Craig, Kooloonong, said the winter crop in the Mallee was a mixed bag with soil type and management practices the main drivers of whether a crop was successful or not.

“The lighter soils that were able to have seedbed moisture at sowing got the crop up,” he said.

“A lot of people, particularly in the central to northern Mallee, had soil moisture from five inches (125mm) of rain that fell in early December the previous year. Tapping into that moisture was a big thing. That is where that soil type became favourable because it meant the crops were able to access the moisture when there was no rain.

“A lot of areas had between two inches (50mm) and four inches (100mm) for the growing season. In many cases that was almost for the year. It is hard to grow a crop on that sort of rainfall, but some growers averaged 1.0 to 1.5t/ha with some pockets going to 2.0t/ha. That was a good result for both wheat and barley.”

Mr Craig said lentils had been one of the disappointing crops in 2018, along with canola.

“Lentils went between 0.4t/ha to zero. At current prices it is hard to make any money out of them, but that can change when prices go up,” he said.

“Canola, unfortunately, never got the establishment period to germinate, and then when it did it was too late. Those crops really struggled. They were somewhere between zero to 0.4t/ha. A lot were cut for hay.

“Generally, I think most people carried over a fair bit of money from previous years and needed to come somewhere close to break even. Being able to carry over some income from previous years helped.”

New South Wales

NSW bore the brunt of the severe drought that hit the eastern seaboard in 2018, and is still continuing in some areas.

With harvest wrapped up, GrainCorp has taken in a paltry 607,700t from NSW, a far cry from the bumper year of 2016 when the state produced 6.566Mt.

AMPS Agribusiness consulting agronomist, Tony Lockrey, Moree, said in the north west of the state only about 10 per cent of the intended winter crop went in and got away on time, mostly with zero till and deep sowing.

“There was probably another 40pc went in dry in the end. That was much more than was intended, but each time a new rain front was predicted we’d put another paddock in of a different variety. Some growers ended up planting their whole farms dry which was a big risk,” he said.

“Then it was a tale of two rainfall events. We had a fall of 10 to 30mm at the beginning of July that brought up some of the dry-sown crop. A lot of that then proceeded to die and some of it hung on, which made it difficult to manage with split germinations and stressed weeds.

“Then we had a reasonably good fall of rain at the end of August. That was perfect timing if the crop was in good shape at flowering time, but a lot of the dry-sown country, while it still survived, brought it away again. Then we had to make a lot of calls on which paddocks to keep and which ones to can.”

Mr Lockrey said a soft September/October and a few more showers ended up producing a grain result that was better than expected, but still well below average.

“Individual paddocks that we thought would top out at 1.25t/ha went 1.5t/ha, and anything that went 2t/ha or better really rang the bell because the price was good. Growers were able to sell APH1 wheat for $440-$460/t, depending on whether delivered or on-farm, and barley at high $300s/t.

“Retained moisture, good weed control, good fallow management leading up to the winter was a massive factor (in producing successful crops). Even then you still had to get under the right falls. It didn’t guarantee you a crop, but it got you a lot closer to the mark.”

Mr Lockrey said stubble retention was also a big factor in crop success.

“Bearing in mind we had had record chickpea crops the two years prior, a lot of those paddocks were bare. We were really looking forward to get wheat in and getting cover back on those paddocks, but a lot of them missed out. They are bare-looking blocks now. Any storms are hitting them and running off and not wetting them up properly.”

In southern NSW, it was a year of mixed fortunes with some areas, such as around Barmedman, experiencing complete crop failures through to other regions, such as the eastern slopes, having a relatively good year.

Delta Agribusiness senior farm consultant, Tim Condon, Harden, said the story of the past winter crop was all about moisture.

“Those growers who did a good job of conserving moisture from the previous December/January with really good fallow management were able to get crops earlier and did okay,” he said.

“The winners were those who had really good summer fallow management, planted on time and applied early nitrogen to get early crop vigour so the roots could get down and get into the moisture.”

Mr Condon said drought stresses and frost in some areas impacted crops, forcing growers to make decisions about cutting them for fodder or running them through to grain.

“People used many ways to exit the crop, whether through hay or silage, grazing or taking it through to grain. It was horses for courses across individual farms. Where people did cut for fodder, they were able to sell it for pretty good prices,” he said.

Queensland

Winter crops in Queensland equally wore the impact of the drought with GrainCorp taking in only 107,900t from the sunshine state compared to 1.787Mt in the bumper year of 2016.

In Central Queensland, Spackman Iker Ag Consulting principal, Graham Spackman, Emerald, said the winter crop, which was early and finished up at the end of September/mid-October, produced yields that were well below average.

“There were some farms that did okay with yields around 1.0-1.25t/ha with chickpeas and 1.0t/ha with wheat. But there were a lot of others that got much less than that,” he said.

“And there was a large area, particularly in the northern highlands, that didn’t even get a winter crop in.

“Everyone is sweating on a summer crop now. It has been a while since we have had a good, general summer season through the highlands. Last year there was reasonable late-planted sorghum in some parts, but not a big area of it.”

On Queensland’s Darling Downs, Elders agronomist, Jordan McDonald, Dalby, estimated only about 10pc of the normal winter crop planting went in across the region.

“There was a mixture of wheat, barley and chickpeas. Where growers chased the moisture down, chickpeas was the only crop they could get in in some situations,” he said.

“One of the lessons was that coming off the back of growing a lot of chickpeas over the last couple of seasons, many paddocks suffered from low stubble cover. Where there was stubble cover it was easier to wet up that country and get a crop in.

“There was rain late in the season on crops that looked like a failure but ended up coming to something in the end. There were good grain prices, so what we thought was a complete disaster ended up with growers being able to harvest some of those crops.”

Grain Central: Get our free daily cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY