Back Paddock agronomist Dr Chris Dowling speaking at the GRDC Goondiwindi Update on March 1.

AN OVERDEPENDENCE on applied nitrogen is fuelling a nutrient rundown in the northern region’s soils that can be addressed by strategies that boost mineralised nitrogen and monitor reserves of other nutrients.

That was the message from Back Paddock Company technical services manager Chris Dowling in his address to the Grains Research and Development Update held in Goondiwindi on February 28-March 1, and as the concept of nitrogen budgeting in Australia hits its thirtieth birthday.

In that period, Australia’s use of nitrogen fertilisers has quadrupled because of the larger area cropped, and higher rates applied.

Dr Dowling said some of the northern region’s soils were the most fertile in the world when they were first farmed, but now rely heavily on nutrients being applied at big per-hectare rates.

“By and large, in my estimation, a lot of these soils that were producing 100 to 200kg (mineralised N) are down to 20 to 40 a year now,” Dr Dowling said.

“That potential to produce nitrogen from the soil — that natural capital that we’ve turned into equity in the farm — has now plateaued.”

“I think we’re in the situation now where more than 50 percent of the nitrogen that the crop sees will have to come from fertiliser because the systems are run down and…that’s not a very good place to be.”

“At some stage, that needs to stop or that system’s going to collapse.”

Low point reached

Most of the region’s growers have had three bumper winter crops in a row which have consumed nitrogen mineralised during the enforced long fallows of the 2017-19 drought.

“As the drought continued on, the soil nitrogen continued to increase until we got to 2019.”

Dr Dowling said that was when mineralised nitrogen peaked.

“The same thing precipitated the formation of nitrogen budgets 30 years ago.”

Speaking to Grain Central after the Update, Dr Dowling said some of the soils of southern Queensland and northern NSW, with their famed water-storage capacity, were now at around one-eighth of their original mineralising capacity.

“They were able to mineralise two seasons’ worth in one year.

“They are now down to mineralising less than a quarter of their capacity.”

Penalties inherent

At the update, Dr Dowling said a lack of mineralised nitrogen in wetter years, when crops yield well but cannot be top dressed at the ideal time and rate because of logistics issues, has seen wheat protein fall away.

This has created a dependence on the grower’s ability to apply fertiliser at the ideal time and amount to maximise yield and protein results.

“It really comes down to every decision you make about nitrogen will be about the weight, the placement and the timing that you put it on.”

Dr Dowling said mineralisation offered flexibility when rainfall arrived in amounts above the forecast range, and at unexpected times.

“It’d be nice to have the soil make that decision for you.”

“The soil responds before most of us managers do.”

“By and large, we tend to be conservative; we put off decisions and we miss windows, particularly as we move north.”

Dr Dowling said a lack of mineralised nitrogen has contributed to crops being able to hit yield or protein targets, but not both.

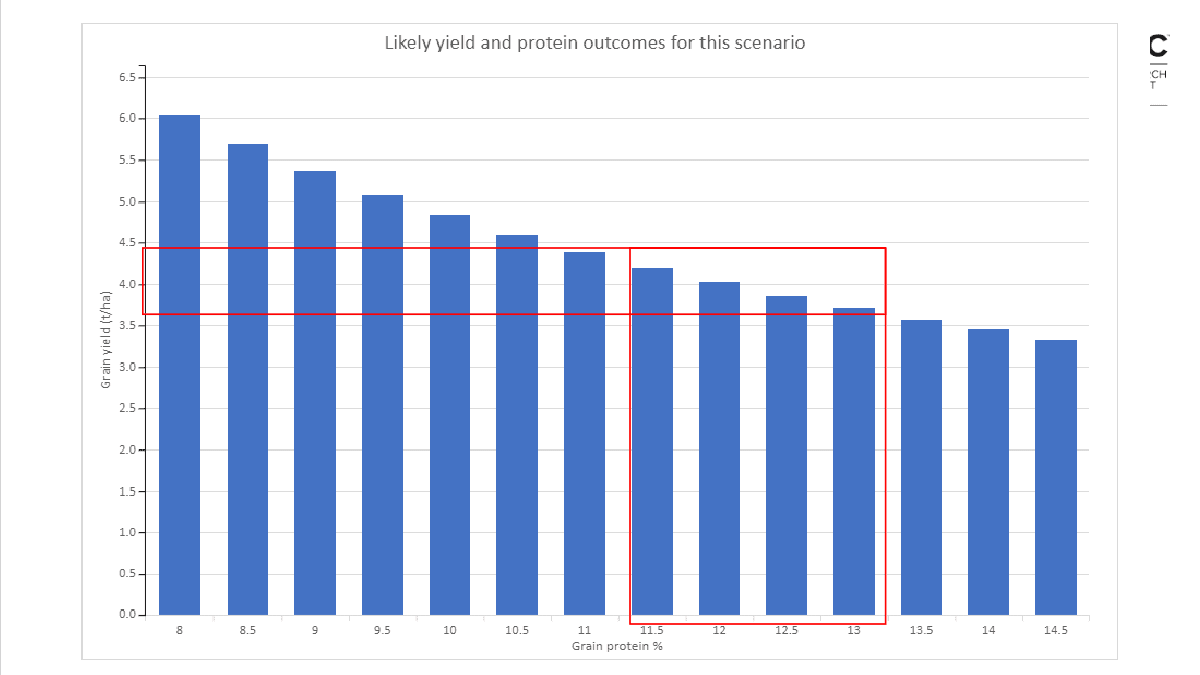

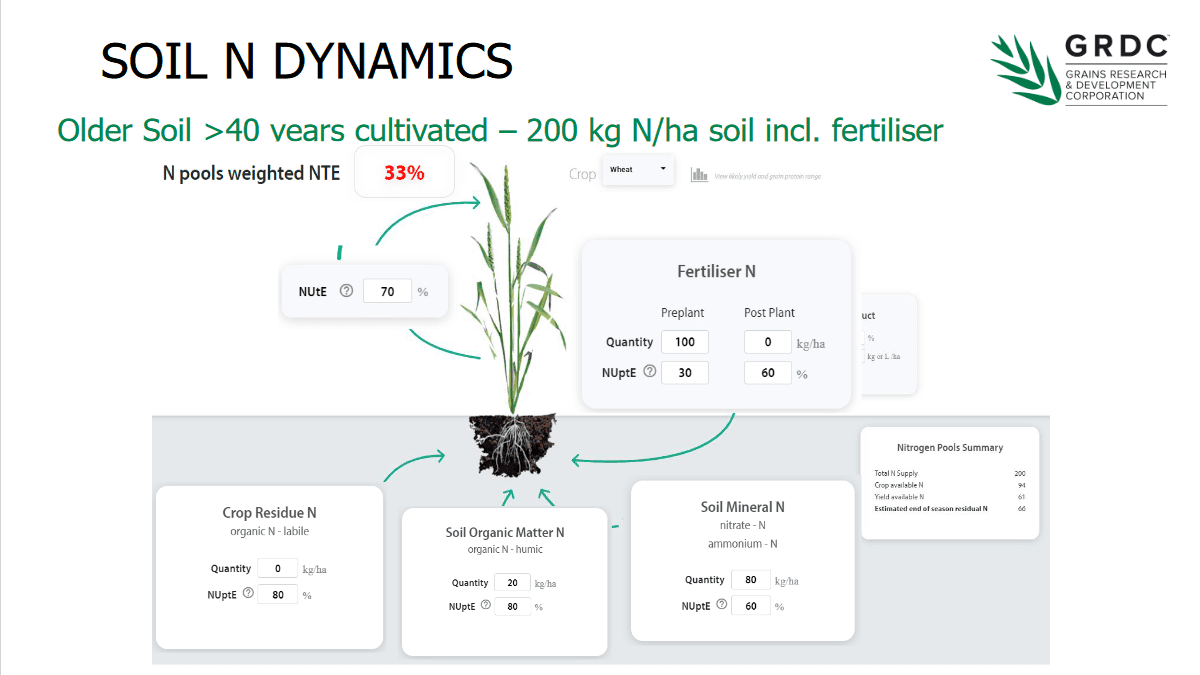

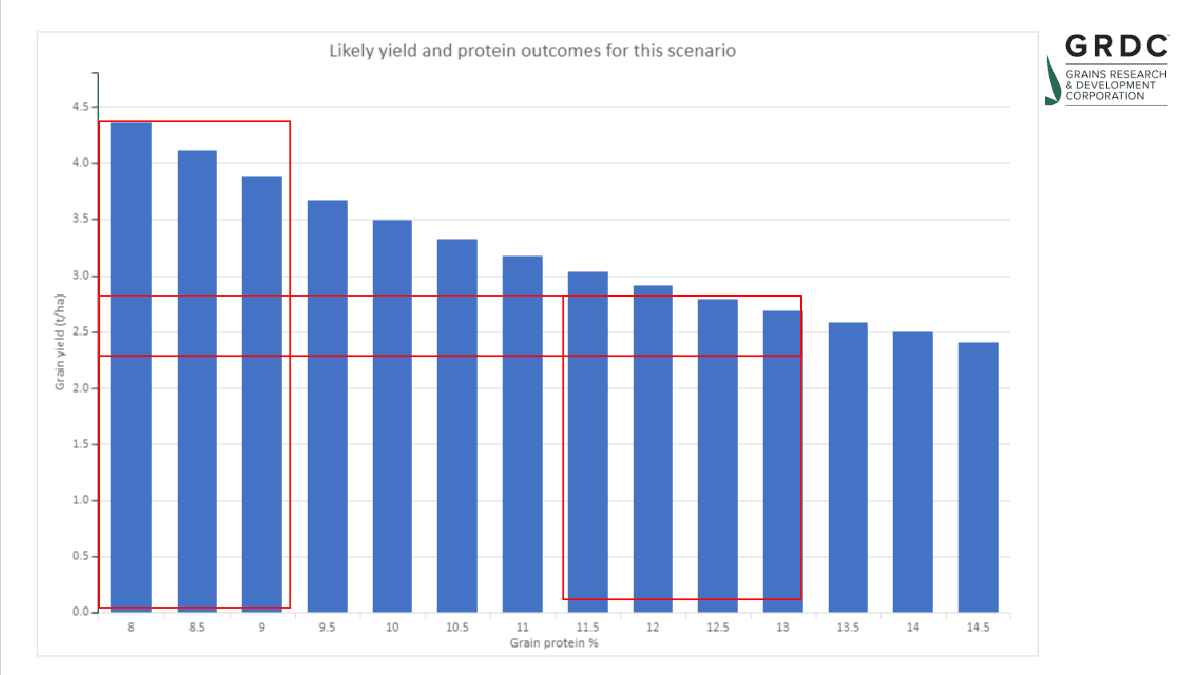

He said an example from the Moree region (see graph 2, older soil) showed a wheat yield of around 2.5t/ha and protein in the target range of 11.5-13pc, as needed to make Hard or Prime Hard specifications, in seasons where water is limited.

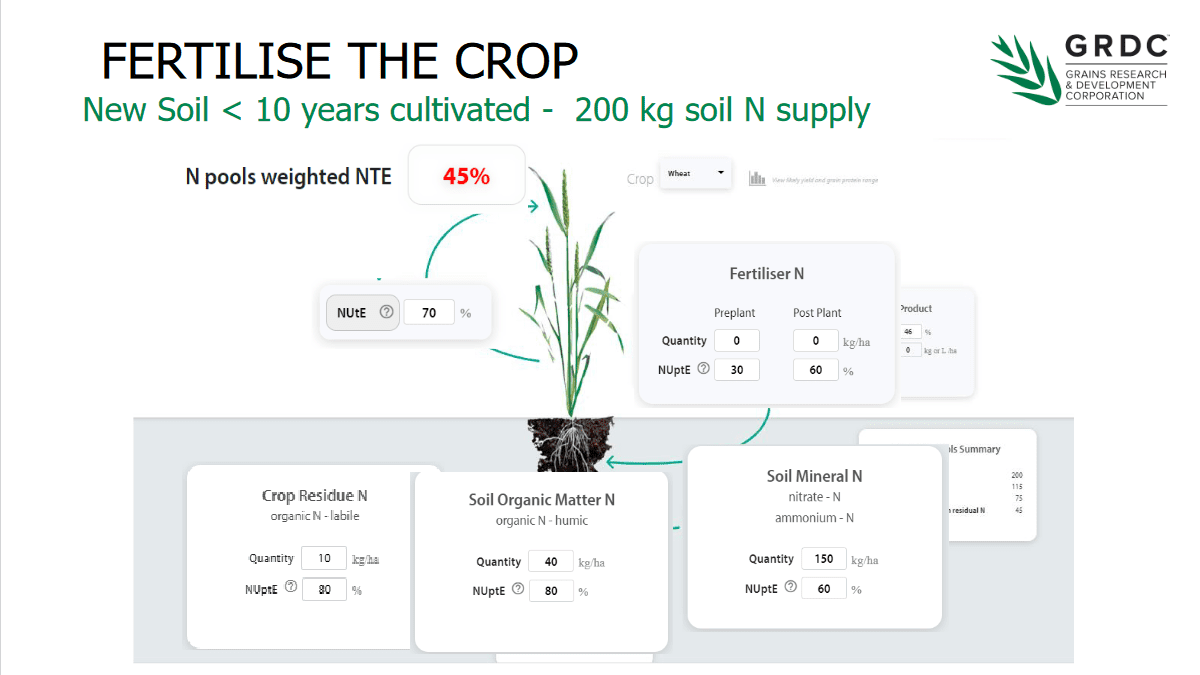

In decades past, Dr Dowling said kind seasons would allow yields of 3.5-4.5t/ha, and protein of more than 11.5pc (graph 1 and graphic 1, new soil).

“If the season comes along where (crops) don’t have water limitation, we’re going to end up with (yield) around the 4t and around 8-9pc protein and that’s exactly what we saw in 2011-12.”

“With reasonable moisture, the problem is going to be the protein.”

Graphic 1: Modelled nitrogen utilisation efficiency (NUtE) for a wheat crop in the Moree region in a paddock’s first decade under cultivation. Source: Back Paddock Company

Graph 1: Likely wheat yield and protein outcomes for scenario shown in Graphic 1. Source: Back Paddock Company

Graphic 2: Modelled nitrogen utilisation efficiency (NUtE) for a wheat crop in the Moree region in a paddock’s fifth or greater decade under cultivation. Source: Back Paddock Company

Graph 2: Likely wheat yield and protein outcomes for scenario shown in Graphic 2. Source: Back Paddock Company

Equation needs rethink

Referring to research by Northern Grower Alliance’s Richard Daniel, Dr Dowling said the uptake of residual nutrients can be greater than that freshly applied.

It is one reason Dr Dowling sees flaws in the equation widely used to calculate applied nitrogen requirements, and brought into play following drought in the early 1990s.

“Thirty years on, I don’t think the old rules of thumb actually work.”

“It relates to the way budgets are done: yield times protein times two minus the soil test value and there’s your nitrogen rate.

“That ‘times two’ assumes that all pools of nitrogen are equal, they are all supplying equal amounts at equal efficiency and clearly that is not the case.”

He said measuring removal of nutrients through grain harvested was equally flawed, as it frequently under-indicated the draw-down, particularly in depleted soils.

He said he thinks we have the nitrogen budget “totally wrong”.

“What’s happened over time is we’ve gone into maintenance mode and unfortunately probably in a lot of cases, particularly with nitrogen, we went straight from maintain to overuse when we really should be building it.

“We missed the opportunity just to go into a maintenance mode.”

Dr Dowling has estimated efficiency of organic nitrogen from both crop residue and soil organic matter at 80pc.

“That’s because it’s dribbling out when the crop has roots in the ground.”

Dr Dowling said nitrogen not well distributed in the soil profile can have an efficiency rate as low as 10pc.

Other factors on radar

Dr Dowling said a decline in levels of soil carbon and nutrients including potassium all needed to be at least arrested.

“Not replacing organic mineralised nitrogen is contributing to the further decline in soil carbon; I think that’s what’s being reported quite commonly now,” Dr Dowling said.

“We’ve used natural capital of nutrients by not applying them each year that we’ve removed them to gain equity in the farm.

With potassium, we’ve consumed to the point where we’re going into maintenance mode, and unfortunately it’s a one-to-one relationship going that way, but it might be many-to-one going the other way.

“Once we run it down, it takes more nutrient to build it up than we actually put out because of the inefficiencies in the system.

“We need to be careful with some of the other ones (nutrients) that we don’t miss that opportunity.”

“Post-flooding, I am very concerned that one of the things that’s going to impact, particularly in riverine flooding, is soil structure and its effect on nitrogen availability.’

Path to mineralisation

Several presentations at the Goondiwindi Update pointed to the benefits of greater crop diversity through the inclusion of pulses, legumes and/or cover crops to boost productivity in the longer term.

They came from researchers including CSIRO’s Dr Lindsay Bell, Jonathon Baird from the NSW Department of Primary Industries and Andrew Erbacher from the Qld Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

Likewise, Dr Dowling said a more diverse mix of crops can be beneficial for soils and profits.

Dr Dowling said a quick fix is unlikely to exist, but looking at nutrition requirements for the farming system rather than in the light of just one crop would be a start.

“Reporting a response on a single year is really misleading.”

“Some of the responses in pulses you can’t add up in the nitrogen economy, and you have to question: Are there biological and physical characteristics that those rotations bring that we don’t get out of monocultured crops?

“It’s not just about the nutrients.”

Dr Dowling said mixed-farming systems that include legumes, a greater frequency of pulses and even ley pastures all had potential to boost mineralised nitrogen levels.

“Something’s got to get some more nitrogen into the system.”

One means is a by-product of what for some was a sodden and disastrous end to the 2022 winter-cropping season resulting in unharvested or partially harvested crops.

“Not all is lost because that nutrient that’s in the grain will turn over, it is in organic form.

“If that grain rots in the ground, or it germinates, and we terminate it, that’s going to be a net nitrogen input.”

He said faba beans looked to have the most value in their unharvested form, and could put 50kg/N into each hectare, with up to half potentially available to what will be planted this year.

Aside from applied nitrogen, Dr Dowling said nitrogen could be available to crops from stubble or residue, most of which dissipates three years after harvest, the humic pool, and the soil mineral pool.

“(It) is a combination of residual fertiliser applied from last year plus any mineralisation that’s taken place in the fallow period.”

Grain Central: Get our free news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY