COVER crops are proving an effective way to improve ground cover protection, increase water availability and lift the yields of subsequent crops in northern farming systems.

In a project covering trials from Goondiwindi in southern Queensland to Yanco in southern New South Wales, researchers are aiming to quantify the impact cover crops have on fallow water storage and crop growth.

They are seeking to determine how much water is required to grow cover crops with sufficient stubble, how these stubble loads affect the accumulation of rainfall, what the net water gain/loss for following crops is and what are the subsequent impacts on crop growth and yield.

Queensland Department of Primary Industries extension officer, David Lawrence, said previous work 15 years ago suggested growing cover crops to try to store more moisture across the fallow period could boost yields.

“The interesting thing there was the yields were higher than we could explain just by water alone. There was something else involved,” he said.

“We are re-investigating the water effects (in today’s trials), looking at how long should you grow a cover crop for before you spray it out so it doesn’t use up too much moisture. Then, can you use that extra cover to get better infiltration and less evaporation and actually store more moisture for the next crop.”

Dr Lawrence said millet had traditionally been one of the cover crops people grew because it could be planted in early September and sprayed out six to eight weeks later to trap moisture in the long fallows across summer leading to the next winter crop.

If the crops were allowed to grow through to maturity and grain fill it would lead to significant stored soil water loss and low yields in the subsequent winter crops.

However, earlier trials showed that if the crop was sprayed out within six weeks there were only small water deficits or even water gains accrued to the subsequent crops, with average grain yield increases of 200-300 kilograms/hectare.

Dr Lawrence said although it was still ‘early days’ for the current project, two trials in the Goondiwindi area were showing interesting results.

One of the trials at Yelarbon is an irrigated cotton system with a rotation of cotton/cover crops/cotton, using a range of cover crops: barley, vetch, barley and vetch, and a mix of species.

The other is a dryland system at Bungunya coming out of skip row sorghum which leaves big bare areas, lots of potential for runoff and low infiltration in the skip rows. There the cover crops being trialled are millet, sorghum, lablab and mixtures of those.

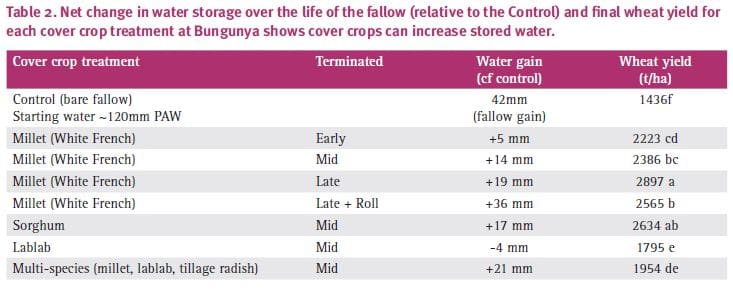

The trials so far have shown that cover crop treatments can increase fallow moisture storage, resulting in higher yields and more profitable grain and cotton crops. However, if they are allowed to grow for too long there could be soil water loss.

“We have found that we have been able to store more moisture, 20 millimetres up to even 40mm over the last season at Goondiwindi, which was surprising as it wasn’t particularly wet,” he said.

“What is really surprising is that, because there was the extra moisture, there was better establishment. We returned over $300/hectare this season in the wheat crop.

“We don’t expect that to happen very often because the advantage from the grain from the extra water storage was about $100. But there was an establishment effect, or something else going on. We know the roots are extracting water from deeper with the cotton, and also with the wheat, following the cover crop.”

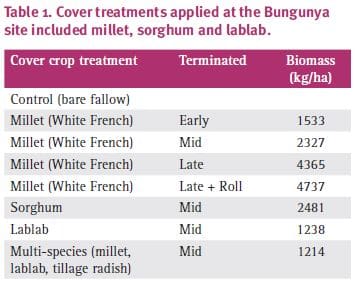

A range of summer cover crops were planted and sprayed out at different times at the Bungunya site to assess their impact on the soil water storage during a long-fallow period after skip-row sorghum, prior to planting wheat.

Dr Lawrence said the initial results at Bungunya showed an impact on the subsequent wheat crop that was far beyond what could be expected from the increases in net soil water storage across the fallows alone.

“Improved establishment of the following wheat crop is an obvious contributor in this experiment,” he said.

“However, there was also greater water extraction from some treatments (especially at depth) in the ‘sister’ cotton experiment at Yelarbon. How much of the responses can be attributed to these factors, how often such results might occur, and the contributions of different factors remains to be explored.”

The stubble effect three days after ~30 mm of rain at the Bungunya site. A ‘Late + rolled’ treatment is in the foreground with a ‘Control’ plot visible behind it. The theory is that stubble reduces evaporation and keeps the soil surface wetter for ~21 days, so if more rain falls in that time, more water will be stored.

When it came to comparing which cover crops were the best for farmers to use, Dr Lawrence said it was hard to be definitive.

“Some people have used oats as a cover crop, but we would not suggest that because it is bred to be leafy rather than stemish, it falls over and doesn’t stand up,” he said.

“We are happy with the wheat and barley, although there are some disease issues you have to be very careful of. The millet was very good, but it can be hard to establish.

“Sudan grass cross sorghum performed very well. If you have tough conditions, maybe sorghum is something to look at as a cover crop.”

Key findings so far from the Bungunya dryland cover cropping trial:

- Summer cover crops can be very profitable; improving ground cover and increasing fallow water storage in long fallows to improve grain yields and boost returns in northern farming systems.

- A later spray-out produced additional levels of a cover that is more resilient and stored more water in the longer fallow. Delaying spray-out too long reduced fallow water storage considerably.

- Using summer cover crop saved two fallow herbicide sprays and dramatically improved establishment of the subsequent wheat crop.

- Yields and returns were increased by the cover crops, and yields were well in excess of those expected from the increased soil water storage alone.

Key findings so far from the Yelarbon irrigation cover cropping trial:

- Winter cover crops can improve ground cover, increase Plant Available Water and improve subsequent cotton yields in pivot-irrigated systems.

- The early spray-out treatment was the best cover crop for storing water over the short fallow in this study where cover did not have to last very long. However, the extra cover in the mid-terminated cover treatment continued to boost infiltration in the cotton’s early growth stages.

- All cover crop treatments improved the yields of cotton by approximately 3 bales/ha; well in excess of any gains expected from the increased fallow soil water storage.

The trials are jointly funded by GRDC and CRDC

Why spray at all? Why not mow down or roll over the cover crop?