A surge in exports of Ukrainian sunflower seed has contributed to a drop in north-west Europe’s vegoil prices. Photo: Feed Ingredients

VOLUME imports of Australian canola and Ukrainian sunflower seed have contributed to a sharp drop in European vegetables oil prices to lows not seen since late 2020, according to analysis from Argus Media.

The insights were presented in a webinar last week entitled The Russia-Ukraine conflict’s impact on global agriculture & fertilizer markets, with global editorial manager agriculture Jade Delafraye speaking on grains and oilseeds

Vegoil oversupplied

Ms Delafraye said in light of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the most dramatic price declines have been seen in vegoil markets, with Australia a contributor because of its “very strong” canola crop.

Australian Bureau of Statistics data indicates Australia exported a record 3.4 million tonnes (Mt) of canola in the six months to March 31, the first half of its marketing year.

This is up 28 percent from the record 2.66Mt shipped in the corresponding 2021-22 period, with Europe the major destination in both cases.

Crushing of the EU’s own oilseeds, as well as imported soybeans, canola and sunflower seed, have flooded the local market, and Ms Delafraye sees little upside in the near term from export parity.

“North-west Europe’s prices have had to come down to a level where vegoil exports to the rest of the world become attractive,” Ms Delafraye said.

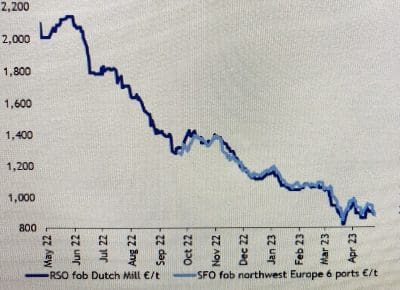

Indicative prices for rapeseed oil and sunflower oil in north-west Europe. Source: Argus Media

“At the moment, the EU is oversupplied in the vegoil market.”

Graph 1: Vegoil prices in € per tonne in north-west Europe. Source: Argus Media

Ms Delafraye said sunoil prices in north-west Europe dropped early last week.

“That’s something to watch out for in the next few weeks and months.”

Prior to the Russian invasion, Ukraine crushed the vast majority of the sunflower seed it produced, and exported the oil.

With the country under attack, crushing at most Ukraine plants has been suspended, and traders are exporting seed instead of oil as a less risky option.

Ukraine shipped around 80,000t per month of sunflower seed to all destinations prior to the Russian invasion.

“After March ‘22, we’ve seen that export capacity has almost doubled.

“We’ve had several months of 160,000t…to all destinations.”

Wheat buys demand

Ms Delafraye said European prices for wheat have fallen faster than corn, partly in response to increased sales of Ukrainian product into Europe when the Black Sea corridor was closed last year.

This has seen wheat buy increased demand in the feed sector, and the size of stocks is weighing on all complexes in Europe.

“We’re in a situation where the market is well supplied and demand is muted.

“Stocks in some of these countries are full, particularly in Romania and Bulgaria.

“We’re in a situation where some unhappiness has emerged…as Ukraine flows turn up en masse.”

Ms Delafraye said decisions by some European countries, and by the EU, have stemmed the sale of Ukrainian grain and oilseeds in Europe.

A ban on its sale, but not transit to export, is in place until June 5 in Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia and Romania in order for local carry-outs to be reduced ahead of new crop.

“As long as transit remains possible, the impact on the global market should be limited.”

Ms Delafraye said a prolonged EU ban on Ukrainian sunflower oil could be significant for world pricing.

“It could have more of an impact than what we’ve seen on grain.”

Corridor’s future clouds outlook

Ms Delafraye said the market cannot be assured the Black Sea corridor will remain open in the longer term.

“There are now growing uncertainties as to whether it will get renewed beyond the 18th of May.

“We’re seeing rate of inspections decrease.

“In the past week, there were only six vessels leaving through the corridor.”

This was down from the peak seen in September when one week alone saw more than 55 vessels able to leave Ukrainian ports.

“We could see a return to Ukraine crushing, but will it do that if its exports by sea are uncertain?”

Ms Delafraye said if the Black Sea corridor was to throttle Ukraine’s ability to export wheat, the impact on global wheat markets would be minimal.

“There is plenty of wheat to go round.

“Because of strong ending stocks expected in Russia, Europe and Australia, those countries could ramp up to offset loss of exports.

“This is reinforced by the fact that the Northern Hemisphere is looking to be in good condition, apart from US winter wheat.”

“What happens with the corridor at the moment no longer moves prices.”

With Europe’s spring crops now being planted, Ms Delafraye said Ukraine’s farmers were well and truly aware of the uncertainty facing marketing avenues for their crops should the Black Sea corridor close, and the war with Russia continue.

“Farmers also face this uncertainty of export routes and therefore may be uncertain about planting as much as usual.

“All in all, it could take Ukraine years to return to where it was.”

Urea prices sink

Mr Nash said supplies within the global fertiliser market were now stabilising after disruptions which started during COVID, and escalated when Russian invaded Ukraine.

“Geopolitical impacts have now largely played out,” Mr Nash said.

“It’s important to remember that supply has actually risen for nitrogen and phosphorous…in Russia.”

In the short term, Mr Nash said nitrogen-based fertiliser is in ample supply, and prices have responded.

“Urea is weak; that’s on oversupply, particularly from China.”

This is in stark contrast to COVID and freight-related disruptions of two years ago which drove up prices prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“The market had already gone through the back of an existential crisis.”

In response to the Russian invasion, sanctions by some of Russia’s fertiliser customers on some executives of Russian companies prompted those individuals to resign to allow companies to resume exports.

“The upshot is that there were no official sanctions put on Russian fertiliser products.”

Mr Nash said the shutdown of the pipeline into the Black Sea removed 240,000t a month of Russian ammonia from the global supply.

“After the COVID lockdown (and) freight squeeze, we also saw crucially an impact on gas prices in Europe…that curtailed nitrogen production in Europe, and that forced increased reliance on urea imports into the European arena.”

Mr Nash said that influx of imports, as opposed to domestic production from Russian gas, caused unexpected supply-side shocks.

“New supply sources are opened up (and) Russian material…continues to flow.”

“The concern dissipates and it dissipates quite quickly as other market sources come on line.”

Russian urea exports by destination in 2021 and 2022. Source: Argus Media

High prices also sparked increases in production of DAP and MAP as well as urea to adequately supply global demand after supplies tightened up to last year.

“Ammonia was by far the most hard-hit.”

Global ammonia prices went from around US$750/t to well north of four digits, and drove up production costs for many fertiliser producers.

High urea prices and tight supplies even lifted DAP imports in Australia from zero in 2021 to 159,000t in 2022.

Mr Nash said Europe’s urea market had traditionally been supplied mainly by North Africa and Russia.

“We saw a significant change in trade flow.”

Europe bought increased amounts of urea from the US, while Russia exported urea made from the gas it was not piping to Europe into non-traditional markets.

“India took an awful lot more; that was a big dumping ground for urea in 2022.”

“Countries took urea from Russia that you wouldn’t normally expect.

“In the past, Russia has distanced itself from India…but it had no qualms about shipping to India in 2022.

Russian urea exports in 2021 and 2022. Source: Argus Media

Meanwhile, Europe looked elsewhere for its fertiliser.

“It took a lot more from the US, more from Nigeria, Saudi Arabia and the Middle East, and we even saw cargoes from as far afield as China.”

HAVE YOUR SAY