INFLATIONARY pressures on food being experienced globally are forecast to narrow the price gap between chicken and red meat in Australia, according to Rabobank senior animal proteins analyst Angus Gidley-Baird.

Presented at a Rabobank event held at the Gold Coast this week to coincide with the Poultry Information Exchange, Mr Gidley-Baird’s talk was entitled Chicken: Making the most of a high-priced meat cabinet.

He said while chicken prices look set reflect price increases as the result of cost-push inflation, chicken still looks like being the cheapest meat choice on the refrigerated shelves.

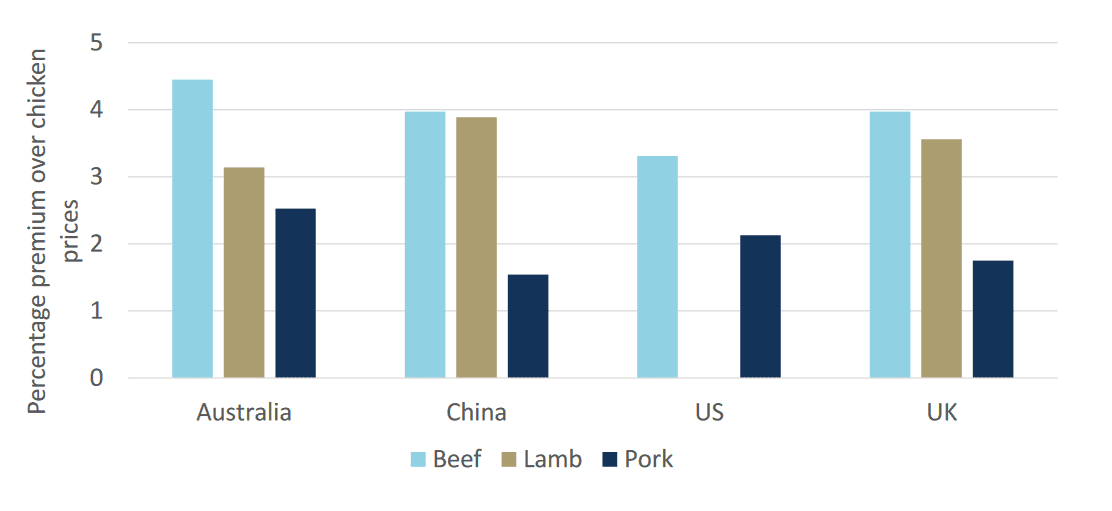

“From a beef point of view in Australia, beef is about four and a half times more expensive than chicken as an average retail price,” Mr Gidley-Baird said.

Graph 1: Price relativity between chicken and beef, lamb and pork. Source: ADHB, USDA, Rabobank 2022

In terms of price relativity, Mr Gidley-Baird said that was greater than in China and the United Kingdom, where beef was around four times the price of beef, and the United States, where it is 3.5 times higher.

“Looking at that, I’d say we’ve got the greatest price spreads between the beef, lamb and pork prices to chicken prices.”

He said one could argue a consumer would tolerate a rise in chicken prices, in part because hikes in beef and lamb prices have already been seen.

“You could probably lift that chicken price up.

“In Australia, we’ve allowed that spread to grow quite wide.”

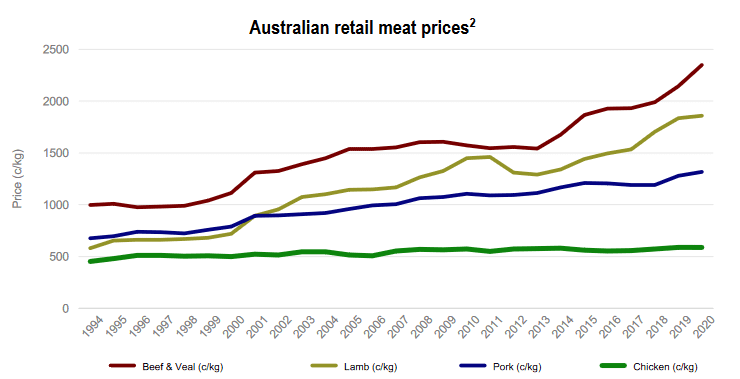

Graph 2: Retail prices of Australian meat in cents per kilogram. Source: ABARES

Increased market share possible

At more than 120 kilograms per person per year, Australia is the biggest consumer of protein including seafood in the world, with the US only just behind.

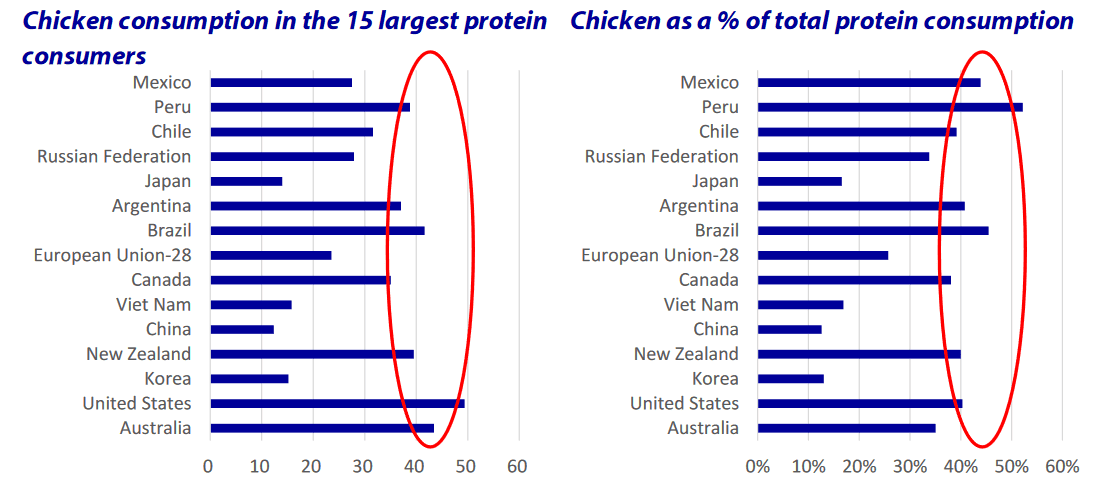

Mr Gidley-Baird said Australia was “right up there” in terms of annual per-capita consumption of chicken at 40 kilograms plus per year.

Graph 3: Chicken consumption and market share in world’s 15 largest protein consumers. Source: FAO, OECD, Rabobank 2022

However, chicken accounts for only around 35pc of the average Australian’s annual protein consumption, compared to 40pc or more for several other nations including Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, New Zealand and the US.

“If you push that Australian consumption up into the realms of 40pc of our overall protein consumption, you could potentially say there’s a 15pc growth in volume allowed in the industry to accommodate that.

“Based on what some of the other countries are doing, we could fit more chicken in our diet at the expense of some of the other proteins.”

Angus Gidley-Baird. Photo: File

On beef and lamb, Mr Gidley-Baird said price rises in Australia have already been seen.

“We’ve seen a change in seasonal conditions, we’ve got one of the lowest volumes of cattle that we’ve seen in the last 35 years…and that’s flowed through into that retail space.

“Lamb had its run a couple of years ago, and since then it’s been more moderate in its growth.”

By comparison, increases in pork and chicken prices have been “very slow”.

Australian Bureau of Statistics March quarter 2022 data shows the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 2.1pc over the quarter, with food up 2.8pc, vegetables up 6.6pc and beef up 7.6pc.

“Meat prices based on the CPI data jumped 12.1pc in the last 12 months, whereas all the others were quite subdued.

“There is the overlying concern about what happens from a cost inflation point of view, and that general consumer: Are they going to be placed in a position where all the other costs have gone up and they are going to restrict their own consumption of food and protein?”

He said he did not expect people to reduce their overall protein consumption because of inflationary pressure, but purchasing habits could change “around the edges”, for example by replacing a high-end beef meal with a more affordable chicken one.

Production climbing already

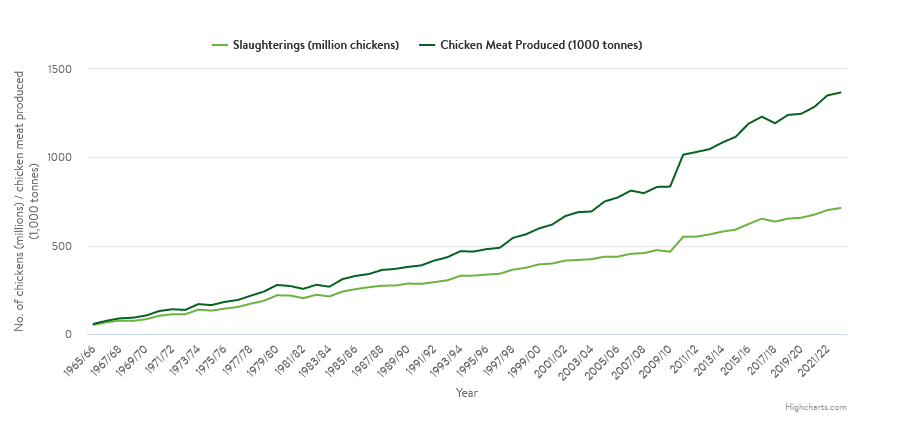

Mr Gidley-Baird said Australia has been increasing its chicken production to new highs, and the demand pull has enabled retail prices to withstand supply-side pressure.

“The market is actually accommodating it.”

Graph 2: Australian chickens slaughtered annually (million) and chicken meat produced (‘000 tonnes): Source: ABARES via Australian Chicken Meat Federation

As food prices globally increase in this inflationary cycle, exacerbated by geopolitical factors headed up by the Ukraine-Russia War, Mr Gidley-Baird said chicken prices may well come to reflect cost-push rather than demand-pull inflation which was prevalent during COVID.

Australia has two dominant processors, Baiada/Steggles and Inghams, and the contract prices at which they sell into Australia’s two dominant supermarkets largely set the retail price for Australian chicken.

“They know exactly how far they can push that before you start flooding the market and they end up hurting themselves because the retailers say they don’t need any more chicken, or they can’t send it somewhere else.”

“You’d have to say there is overall growth available in that market.”

He cited an Inghams report delivered earlier this month which said costs remain elevated across the business, driven mainly by feed, supply chain and transport, and that price increases had already been achieved, with further ones sought to offset cost pressures.

He said Australia’s exports of chicken meat were relatively small, and export is not expected to be the focus on increased production because sales tend to be either lower-value cuts, or go into niche markets like Singapore.

When put up against the world’s biggest chicken-meat exporters, Brazil and the US, Mr Gidley-Baird said Australia would be unlikely to compete.

“We get burnt a little bit on our cost of production.”

Mr Gidley-Baird said the shortage of labour in Australia was “a big challenge” for all meat-processing sectors, and was largely responsible for red-meat processors operating at about 40pc below capacity.

“An average eastern states weekly kill number is about 110,000 head per week from a cattle point of view; we’re currently doing about 80,000 head.

“That’s not because the cattle aren’t there; it’s because they can’t get people on the plant.”

“The only way you can fix that is by paying people more and upskilling people more, which means it’s a long process and a costly process.”

Grain Central: Get our free cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY