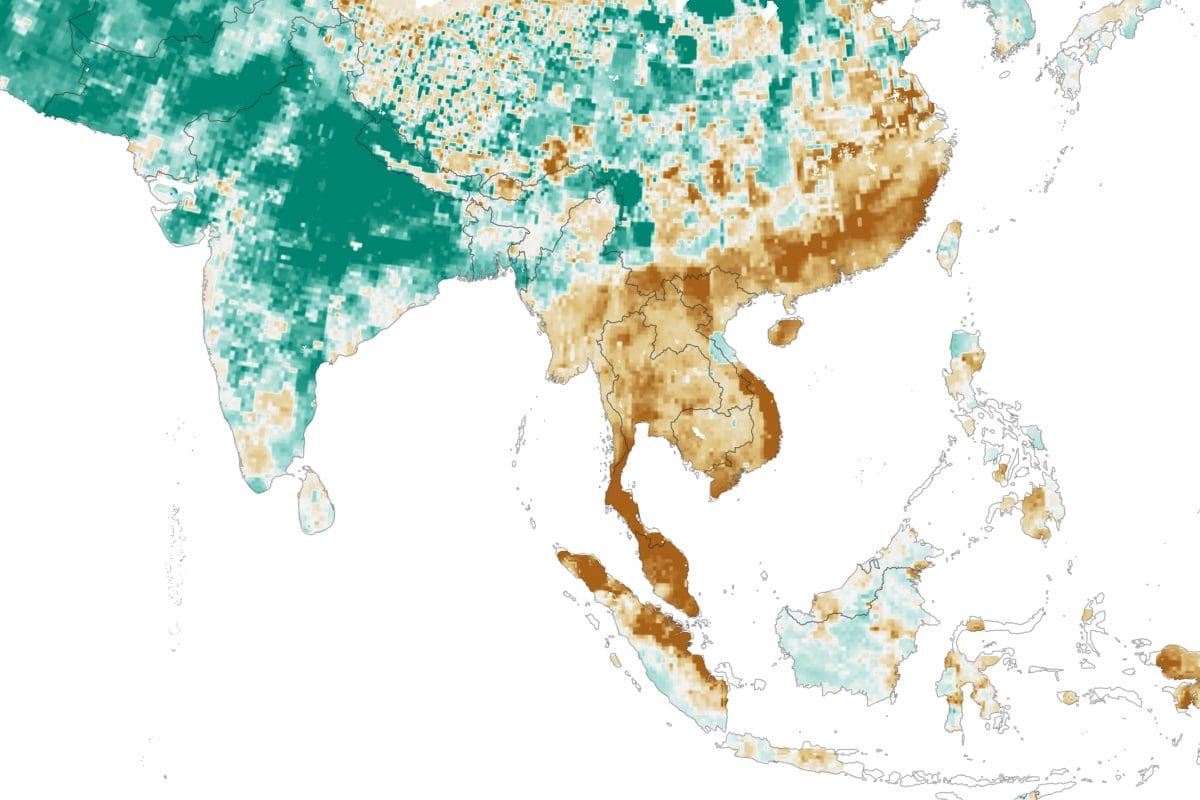

Subsurface moisture levels between 1 January and 7 February 2020. which show the impact of drought in South-east Asia. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

SEVERE DROUGHT in Thailand in the first five months of 2020 has adversely affected the production of off-season (dry season) rice and corn, primarily due to a lack of irrigation water as reservoirs are critically low.

This will decrease the country’s exportable surplus of rice and potentially increase demand for imported wheat and barley in the 2020/21 marketing year.

Most of Thailand’s rice and corn production occurs during their wet season with planting commencing in May and running through to the end of June for rice and the end of August for corn.

The corn harvest commences in September and runs to the end of the year while the rice harvest is concentrated into the last two months of the year.

The dry season production cycle is heavily reliant on the availability of irrigation water. Most of the planting occurs in November and December, and harvest is generally completed by the end of April.

The area planted to dry-season crops fell 36 per cent to 1.4 million hectares relative to the 2018/19 crop year, after historically low precipitation during the 2019 monsoon led to record low water storage inflows late last year. Consequently, production of off-season rice and corn are forecast to decline by 41pc and 25pc respectively compared to the previous season.

Total 2019/20 rice production is forecast at 18 million tonnes (Mt), 14.8Mt in the wet-season production cycle and 3.2Mt in the dry-season window. This is the second-lowest level of production in the last ten years after a severe drought in the 2015/16 season slashed output to 15.8Mt.

Thailand’s corn production in the current marketing year is expected be around 4.5Mt, a fall of 20pc on 2018/19 levels. This was mainly due to an infestation of fall armyworm in the wet-season crop and a dry spell in June and July last year, seriously slowing early crop development.

Demand for feed grain in Thailand in 2020/21 is forecast to remain relatively static at around 20.3 Mt as shrinking swine production, a result of African swine fever, is offset by growing production in the poultry, dairy cattle, and fishery sectors. Nevertheless, this is contingent upon a recovery in animal protein consumption to pre-COVID-19 levels by early 2021 at the latest.

Of the total feed demand, the derived demand for corn is estimated at around 8.5Mt. But even with an expected rebound in domestic corn production in 2020/21, local corn producers will still only be able to supply around 6Mt.

It is this gap, between domestic animal feed requirements and corn production, that will drive import demand for corn, particularly from neighbouring countries like Myanmar, and other livestock feeds such as feed wheat, barley and dried distillers’ grain.

Thai wheat imports are forecast to decrease by 2pc in 2020/21, to 3.2Mt. Milling wheat is expected to make up just over one-third of these imports at 1.1Mt, down from 1.4Mt in 2019/20. The current season imports were higher than normal after flour millers built stocks when the government announced plans to ban the agricultural pesticides glyphosate, paraquat, and chlorpyrifos.

The 2020/21 milling wheat demand could fall even further if the tourism sector doesn’t recover quickly from the effects of COVID-19. Tourist arrivals in March fell by more than 76pc compared to a year earlier, having a devastating impact on street vendors and noodle stalls.

Feed wheat for the intensive livestock production sector makes up the 2.1Mt import balance. The government retains import limits on feed wheat that have been in place since January 2017 to protect domestic corn farmers from cheaper feed wheat imports.

Under these restrictions, importers are required to purchase domestic corn before being permitted to import feed wheat at a 3-to-1 absorption ratio. In other words, to import a tonne of feed wheat, a mill must use three tonnes of domestic corn. The government also set the minimum purchase price for 2019/20 season domestic corn at 8 baht per kilogram, approximately US$252/t, for feed mills.

With lower domestic corn production, these constraints seriously hamper the ability of stockfeed merchants to fill the demand void with imported wheat. This is where imported feed barley comes into the equation.

Last week the Thai Feed Millers Association (TFMA) passed on its wheat tender which had called for up to 227,500t of feed wheat for August to October delivery. It was said the offers were considered too high. The lowest was reported around US$215/t cost & freight (C&F), $10/t higher than expectations.

Maybe this opens the door for more purchases of Australian feed barley. Australian barley prices have recovered somewhat from the sharp drop after the draconian Chinese tariffs were imposed, but at around $195/t C&F Thailand, it is significantly cheaper than the latest feed wheat tender prices.

While not in the same league as China, Thailand has been an increasingly active buyer of Australian barley in recent years. Purchases of 250,000t in the 2017/18 Australian crop season (October to September) increased to almost 400,000t in 2018/19, making them Australia’s third-largest barley customer. At more than 430,000t, purchases in the first six months of this season have already exceeded last year’s total, with almost all of it being feed barley.

South-East Asian countries such as Thailand will not individually replace China as a destination for Australian barley. However, with a significant freight advantage over Black Sea origins, the region can play a critical role in shifting the focus away from China and avoid competing head to head with Black Sea exporters into Saudi Arabia.

This article was written by Grain Brokers Australia.

HAVE YOUR SAY