Drought has reduced production prospects for crops in countries including Thailand and Australia. Photo: International Rice Research Institute

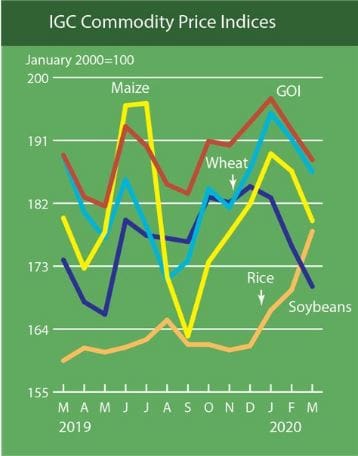

THE INTERNATIONAL Grains Council grains and oilseeds index (GOI) average rice price sub-index has strengthened five per cent in March to reach highs not seen since 2013, according to the April edition of Agricultural Market Information Systems’ (AMIS) Market Monitor.

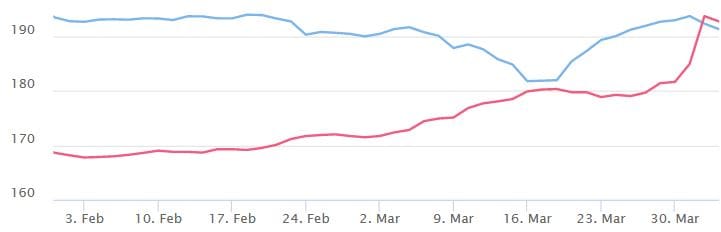

The rice price rise was in contrast to the overall index, the GOI derived from daily export quotations of five commodities, which fell 2pc from February (chart 1). The corn, soybeans and wheat export price sub-indices in March were lower than those in February by 4pc, 2pc and 3pc respectively.

Chart 1. Grains and Oilseeds index shown as the blue line (average of daily observations) was lower in March than in February. The rice index (red line) rose to multi-year highs. Index January 2000 = 100. The GOI comprises sub-indices of barley, corn, rice, soybeans and wheat. Source International Grains Council

Wheat drops despite support

Concerns about the impact of COVID-19 dominate the market last month, and influenced day-to-day movements in wheat prices.

While the longer-term implications for demand were uncertain, a nearby upswing in import buying, including a raft of tenders in North Africa, provided late-month support to export prices.

Logistics problems were reported in some countries as COVID-19-related movement restrictions were introduced.

Although prospects for global supplies in 2020/21 remained mostly good, there were some threats to the overall outlook, and this offered price underpinning.

In the Russian Federation, a weaker currency contributed to a fall in US dollar-denominated export prices and saw an accelerating pace of exports. While the export competitiveness of US supplies was eroded by a stronger currency, confirmation of sales of US milling wheat to China supported sentiment.

Maize ethanol downer, China positive

The IGC maize sub-index fell to a four-month low in March.

COVID-19 worries and spillover from external markets pressured prices across all major exporters. US values were particularly susceptible to the slump in crude oil prices, and sharply reduced fuel and ethanol demand. However, firming was noted towards the end of the month, tied to a modest pick-up in export demand, with new sales confirmed to China.

Average quotations in Argentina declined on a seasonal increase in supplies, and reports of strong yields from the early stages of the harvest. Recent values firmed on COVID-19-related logistics constraints.

Rice a cracker

The rice index (fawn-coloured line) continues to rise, while those again lower this month are the GOI index (red). wheat (light blue), maize (yellow) and soybeans (dark blue). Source IGC in AMIS market monitor.

Rice prices lifted in March to a multi-year high, supported by worries that drought in Thailand would restrict availability on international markets, and amid a heavy uptick in consumer purchasing in exporting and importing countries on COVID-19 concerns.

However, gains were pared by losses in Asian exporters’ currencies against the US dollar, while a slowdown in government procurement and subsequent increase in export availability added mild pressure in India.

Logistics constraints also featured, including a shortage of containers commonly used to ship specialty grains such as basmati and fragrant rice.

Soybeans logistics woes

Stemming from weakness at all major origins, average soybean values dropped by 3pc in March compared with February.

After initial modest gains, export prices fell steeply in sympathy with a plunge in external markets, linked to deepening worries about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global economic activity.

Despite news that China had secured some cargoes from the US for April shipment, underlying export demand concerns also weighed, as reflected in disappointing weekly sales tallies.

Recently, overall declines were trimmed by news of tightening soymeal availability and heightened worries about South American logistics owing to the imposition of transportation restrictions aimed at controlling the spread of COVID-19.

Threat to local food security

In its April feature article, AMIS Market Monitor said it would be populations in vulnerable countries which would be most affected by COVID-19, even though global food markets may be spared.

While the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on global food markets has so far been limited, the pandemic poses a serious threat to food security at local level.

According to official statistics, the virus has not yet spread widely in countries where food insecurity is pervasive, most notably sub-Saharan Africa.

If it did, the outbreak could be expected to have similar effects to previous epidemic-induced shocks such as the Ebola virus, which caused steep harvest reductions, food price spikes and aggravated food insecurity.

Additionally, and perhaps more imminent, is the risk posed by the global economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 crisis, which may compromise import-dependent countries’ ability to purchase foods and cause income losses for households, with acute food-security repercussions.

Agricultural production systems in the most vulnerable countries are predominantly labour intensive.

Quarantine measures, self-isolation and aversion behaviour in response to an outbreak would therefore cut the labour supply, potentially resulting in contractions of crop area, crop management and ultimately crop sizes.

While such effects would immediately dent domestic food supplies, in the medium-term income-earning opportunities, from crop sales for instance, would also be negatively affected.

Moreover, low reserves of food staples, a common characteristic of low-income countries and households, limit the ability to modulate food supplies in instances of production shocks and interruptions to trade, extenuating vulnerabilities.

Concurrently, the slowdown in the global economy and disruptions to global agricultural supply chains have cutback demand for cash and high-valued crops such as fruits, coffee and tea, which are key export-earners in many less-developed countries.

These reductions will translate into income losses for farming households, while national foreign-currency reserves could shrink, with implications for funding of social-safety net programs and the ability to pay for food imports.

Particularly in urban areas of less-developed countries, the slowdown in economic activities and movement restrictions are likely to cut household incomes and purchasing power, factors that would aggravate food insecurity.

If the crisis is of relatively short duration, people could be expected to switch to cheaper but less nutritious foods, therefore resulting in increases in nutrient deficiencies, rather than a broad decline in calories that would result from a prolonged pandemic.

There is a clear reciprocal relationship between health and agriculture, particularly for rural households.

Low levels of agricultural productivity and poor food systems can foster a higher prevalence of malnourishment, increasing a population’s vulnerability to morbidity and the impact of disease outbreaks.

Although immediate interventions are and should be directed to contain the outbreak, this pandemic also shows the urgent need to strengthen the resilience of agriculture, and more broadly calls for increased efforts to eradicate hunger.

Source: Agricultural Market Information Systems (AMIS) Market Monitor.

Grain Central: Get our free daily cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY