Kaspa field pea harvesting in York, Western Australia. Image: WA Department of Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD)

THE UPCOMING election in India, the world’s biggest pulse producer and consumer, has its government continuing to use the blunt instrument of import quotas to manage markets.

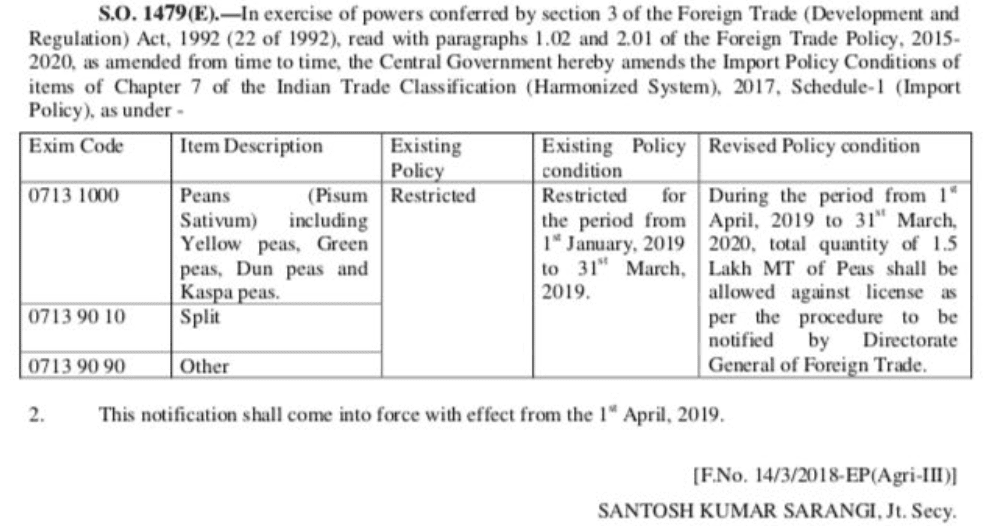

On Friday, and just two days from the end of the previous quota period, India announced a quota of 150,000 tonnes for imported field peas for the year ending 31 March 2020, up from 100,000t in the corresponding year just ended.

While trade in field peas, pisum sativum, has greatest impact for major producers and exporters such as Canada and Black Sea-region producers whose business model grew on the basis of expanding trade with India, the announcement also impacts Australia.

“Australia’s Kaspa pea trade is caught up in the same quota,” GrainTrend director Sanjiv Dubey said.

Mr Dubey said yellow pea and dun pea were the largest importable pea types into India because India grew relatively few of them compared with its predominant production of chickpea.

Further complicating the restricted trade is an ongoing requirement that would-be importers must comply with licence obligations containing some stringent preconditions.

These include proof of mill proprietorship, presumably to channel peas through a mill rather than holding whole peas in stock for later sale.

Chickpea, lentils unchanged

The 60-per-cent tariff applied to chickpeas imported to India remains, as does the 33pc tariff on lentils; the lentil volume is not restricted by quota.

Mr Dubey said Australia’s outlook for lentils this year would depend on whether Canada, the world’s major producer, planted a huge area of red and green lentils.

In summary, restrictions applying on April 1, 2019 for the year ahead are as follows:

- Desi-type chickpea, not restricted by quota, 60pc tariff

- Kabuli-type chickpea, not restricted by quota, 40pc tariff

- Lentil, not restricted by quota, 33pc tariff

- Peas (pisum sativum), 150,000t quota, 50pc tariff

- Mung bean, 150,000t quota, 10pc tariff

- Pigeon pea, 200,000t quota, 33pc tariff

Supply tightening, price lifting

The price cycle for pulses may be turning, according to global agribusiness and commodities market analyst G. Chandrashekhar.

In this month’s Saskatchewan Pulse Market Report, he said the fundamentals of the Indian pulse market were “slowly but inexorably tightening”.

“While there is a feeling among policymakers that the pulse market is well under control, the lurking risks of El Niño-induced dry weather conditions in South Asia in the months ahead can potentially spoil the situation for India.

“It may take another three or four months for the domestic inventory burden to lighten further and make the market more balanced than it is presently.”

Mr Chandrashekhar said prices for pulses appeared to have “decisively bottomed out.”

Australian planting nears

Growers in Australia’s pulse-growing regions are getting close to finalising decisions about what winter crops they will plant between now and June.

In eastern Australia, cereals are expected to be extremely popular, based on their strong price outlook in the domestic market, which is in deficit because of drought.

However, pulses as well as canola have a proven place in many growers’ rotations, and a significant area of pulses and canola will therefore be planted, provided timely and sufficient rain falls.

Grain Central: Get our free cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY