Some wheat is being procured by the Indian Government despite the COVID-19 lockdown. Photo: FCI Punjab Region

THIS season’s Indian wheat harvest has been severely interrupted by the national COVID-19 lockdown.

As it winds down across most states, the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare (MoAFW) has increased its production forecast by almost 1 million tonnes (Mt) to a record 107.2Mt for the 2019-20 marketing year.

Behind China, India is the world’s second-biggest producer and consumer of wheat. This is the first season where production of the country’s major rabi (winter) crop has surpassed 100Mt, but the fourth consecutive record crop after poor harvests in 2015 and 2016.

Excellent late monsoon rains in September last year, and an increase in the availability of irrigation water, provided ideal seeding conditions in October and November, encouraging farmers to increase the area planted to wheat.

The MoAFW estimates that the final area increased by almost 6 per cent year-on-year to 31.1M hectares, implying an average yield of 3.45t/ha.

A steady increase in the government’s minimum support price (MSP) for wheat, in conjunction with an expansion of the MSP procurement operations across most states, has also encouraged Indian farmers to maximise the land allocated to wheat in recent seasons.

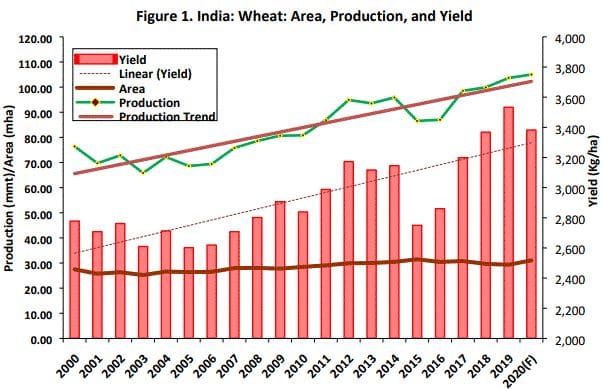

Figure 1. While area has changed little in 20 years yields, and therefore production, have trended higher. Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India and FAS/New Delhi forecast for 2020 (MY 2020/21).

That said, the area has been relatively steady over the past 20 years (Figure 1). Still, average production off that land has been increasing steadily due to improved varieties, higher inputs, improved agronomic practices, and better disease and pest control.

The excellent soil moisture profile at planting, followed by consistent widespread rain throughout the entire growing season, and a relatively low incidence of pests, disease or hail, have been conducive to record production this year.

Lockdown labour shortage

However, the country-wide lockdown, announced in late March to stem the spread of the coronavirus outbreak, led to a severe labour shortage across rural India, crippling harvest activities and hindering the bagging and movement of grain to market.

Although farming has been declared an essential service and agriculture markets are exempt from the lockdown, a shuttered economy left farmers facing enormous challenges. The supply chain has been hit badly: train and bus services have been suspended, and trucks face major hurdles in transiting state borders due to strict checks.

As the record harvest draws to an end, the farmer focus now turns to marketing their grain before it is spoilt. The humid conditions make it extremely difficult for producers to keep the moisture content below 14pc. Any rain only compounds the problem, as very few farmers have undercover storage facilities.

India’s 7000 wholesale food markets are the only avenue for getting these critical food supplies to the country’s 1.3 billion residents, and the nationwide restrictions have severely hit their operation.

Under Indian law, wheat farmers are compelled to sell their grain exclusively at these wholesale mandis to commission agents, who on-sell it to private traders and state buyers. These commission agents typically hire teams of labourers from across the country to unload, clean, weigh, repack and reload millions of bags of wheat on to trucks and trailers, which then transport it to private and government warehouses.

Onus on FCI

The absence of private traders from the market will put the onus on the Food Corporation of India (FCI) — India’s state grain-buyer and warehouser — to purchase a higher proportion of this season’s crop. This will only add to the enormous wheat stockpile already sitting in FCI warehouses.

According to government reports, this stockpile totalled 24.7Mt at April 1, around 26pc of annual domestic demand and more than three times the government-endorsed goal.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, wheat consumption in India is forecast to increase to around 96Mt in the marketing year ending June 30. However, despite surplus domestic supplies and an increasing population, domestic consumption has stagnated since a sharp increase in 2016-17.

With government storages expected to be overflowing in June, the Indian government needs to find a home for the surplus. The high MSP-driven purchasing program has pushed domestic prices to around US$35/t over export parity. However, if prices ease as a result of the record crop and the breakdown in traditional market flows, exports to neighbouring countries such as Nepal, Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka are possible.

Historically, India has been a significant exporter when supply exceeded demand. In both the 2011-12 and 2012-13 seasons, the country exported more than 6Mt. The USDA has India pencilled in for 1Mt of wheat exports in the 2020-21 marketing year, but this is not nearly enough to solve the cornucopia.

Unfortunately, it seems that a substantial quantity will be lost to spoilage as growers battle to bring their produce to market, private traders are absent due to the coronavirus restrictions, and record carry-in stocks have the government struggling to find storage space for higher-than-expected new-crop purchases.

This article was written by Grain Brokers Australia

Grain Central: Get our free daily cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY