AUSTRALIAN agriculture needs to develop a better understanding of what is happening in China if it’s to manage its way through the ongoing Australia-China trade stoush, which is unlikely to end anytime soon.

That was one of the key messages from yesterday’s Queensland Rural Press Club webinar that saw a panel of ‘China watch’ experts address the challenges that lie ahead for Australia’s agricultural trade with China.

Facilitated by the ABC Country Hour’s Arlie Felton-Taylor, the forum featured presentations by Perth USAsia Centre research director, Dr Jeffrey Wilson; University of Queensland senior lecturer, Dr Scott Waldron; and Rural Economies Centre executive director, Associate Professor Ben Lyons.

Australia is not alone in facing the kind of trade dependence tactic the Chinese Government is using. China has a long history of using forms of trade coercion to achieve its international political goals.

Australian farmers have inadvertently been caught in the cross-fire of a geopolitical schism that flared between Australia and China at the start of April when Australia led demands for an independent international inquiry into the origins of the corona virus.

Since then, China has targeted Australian rural commodities with stinging trade measures, slapping an 80.5 per cent tariff on Australian barley imports, banning imports from five major Australian meatworks, investigating Australian wine exports for alleged anti-dumping violations and purportedly telling its millers not to import Australian cotton.

New trade normal

The panel agreed there was unlikely to be a diplomatic ‘quick fix’ to the current situation and Australian agriculture needed to move on and find ways to adapt to the ‘new normal’ of trade relations with China.

Dr Wilson said the Australian rural sector had to work together to manage its way through China’s approach to global geopolitics and protectionism because “we are not going to unscramble this omelette”.

“The discussion really needs to be how industry can work with other industries and the government to do that. That’s what we need to go forward, not hoping there might be some political development where we all go back to 2018 or 2019. It won’t happen.”

Dr Waldron said at the broader level, Australia needed to invest in getting a handle on what was happening within China to understand the forces there and the risks.

“Then we need a coherent strategy to be able to respond. As the agricultural sector comprises different industry groups, it is a discussion we really need to have collectively and proactively,” he said.

Associate Professor Lyons said more than ever Australia needed to get into the policy intelligence space again, which is where it was in the 1990s.

“It worked then in terms of we understood where China was coming from. It will work again. We need to re-engage and understand what the motivations and drivers are, particularly at different industry levels. At the moment it looks like a ‘black box’ of decision making that we are not understanding or comprehending,” he said.

Associate Professor Lyons said the key to Australian agriculture’s success with China in past decades had been the ‘firewall’ that existed between politics and agricultural trade.

“Just as we have our ‘hawks’ on the Australian side, the Chinese Communist Party has a variety of opinions within it. If we can split off the economic benefits from the political idealogues and have the firewall back in place that would be great. We need to rebuild the firewall somehow,” he said.

Challenge to re-engage

Dr Wilson said while some commentators were calling on the Australian Government to “just fix the relationship” with China, there were serious reasons the Australian Government had taken the positions it had.

“Militarisation of islands in the South China Sea is not something Australia can turn a blind eye to for the sake of $200 million worth of barley. I haven’t spoken to a farmer who thinks they should,” he said.

“The conversation has to move on to something more productive as this is the world we are now living in. What can we do around diversification, or around defending against this. Can we go to the WTO (World Trade Organisation)? There are a lot of Plan B options, rather than hoping someone in Canberra fixes it for us.

“If the Chinese trade minister won’t take our phone calls, we can make them by raising a WTO dispute. That will not be a call from Canberra, it will be a call from Geneva. We have a very strong case on barley, beef, coal and maybe cotton.

“The Australian Government hasn’t done that initially in the hope we could talk first. But if they are refusing to talk, I say kick it to the umpire.”

Dr Waldron said it was in Australia’s interests as a small, trading nation dependent on exports to operate in an international system bound by trade rules, investment rules, the law of the sea and human rights.

“That is what the Federal Government has to stick to. I don’t think any amount of pressure from business groups would, or should, change that,” he said.

“Leave Federal policy to the Federal politicians to pursue the national interest, and for business and industry to go about what it best can to manage the risks through product placement, pricing and diversification.”

Barley tariff

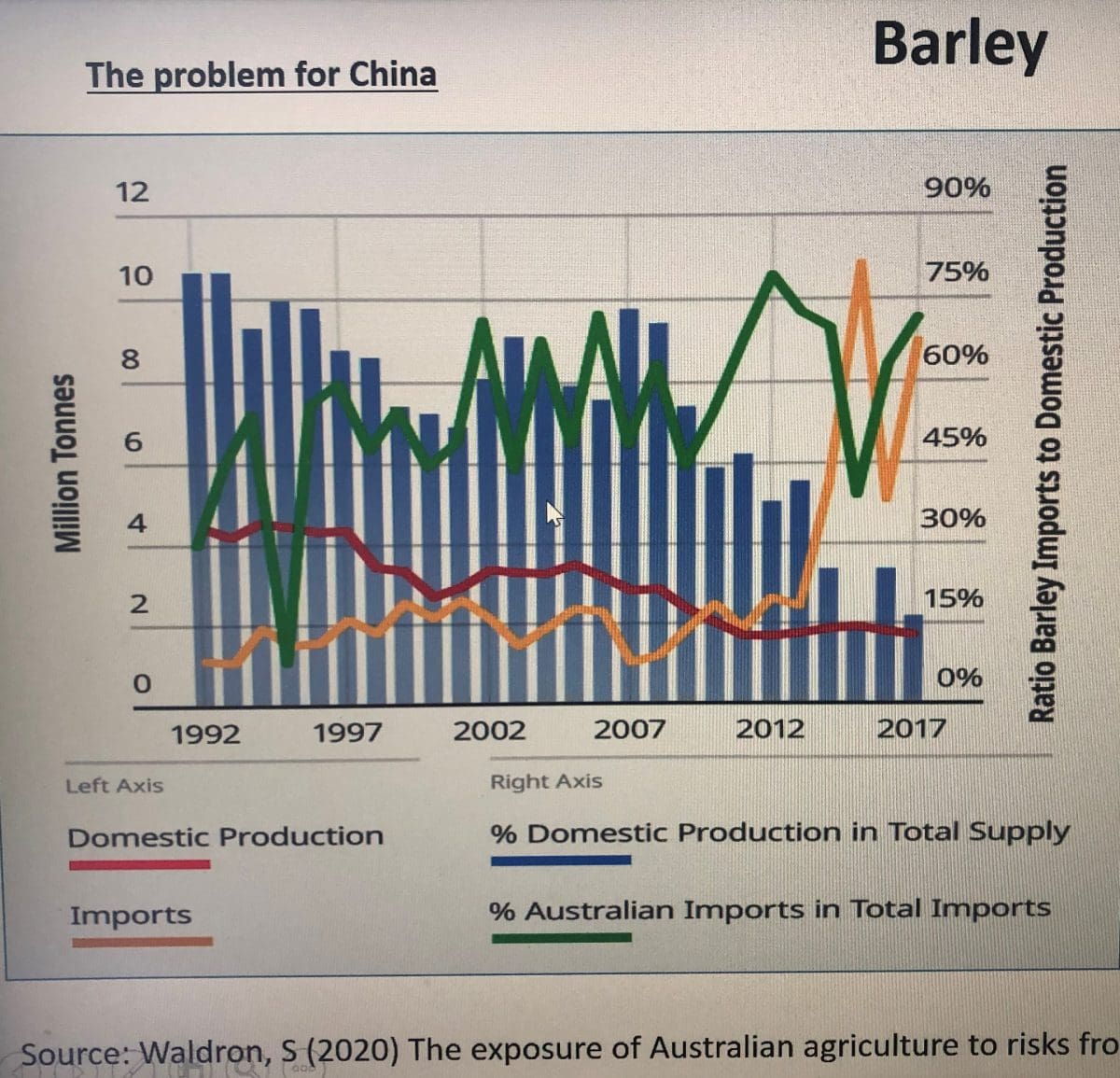

Outlining the background behind China’s move earlier in the year to impose an import tax on Australian barley, Dr Waldron said China’s domestic production of barley had dropped from 4 million tonnes (Mt) in 1992 to 2Mt by 2017.

At the same time, Chinese imports of barley tracked around 2Mt until they rose rapidly in 2013 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: China barley imports.

“The result is that of the total Chinese barley supply use, 15pc came from within China and 85pc was imported,” he said.

“That situation contravenes China’s policy on food security. China wants to be able to produce a substantial amount of its own food to feed its population.”

On top of that, Dr Waldron said in some years Australia accounted for between 70 and 80pc of China’s barley imports.

“This contravenes another set of policies from China about import diversification. China doesn’t want to be importing from singular sources for serious food crops like barley, particularly from a country China sees as not a political ally,” he said.

“As a result, China started the investigation into Australian barley in 2018. The findings came out in May this year. Their arguments were firstly that Australia subsidises domestic barley production, secondly that Australia dumped barley into China at below market prices, and thirdly that that damaged Chinese domestic barley production and barley producers.

“None of them stand up to scrutiny. It is a spurious case.”

Dr Waldron said China was using those instruments to advance its short term and long term interests without “shooting itself in the foot” by taking those measures.

“Underlying that are signs of more structural problems. Within China there are signs of economic nationalism, signs of economic coercion and the dismantling of multilateral trade systems,” he said.

“It is not just a small diplomatic stoush taking place that will be fixed by more refined diplomacy. Some of these issues are serious and structural, and that has to guide our response.”

See also Beef Central story, ‘Boom and bust: Is China bowing out of Australian agriculture?’

Grain Central: Get our free cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

I have exported wine to China for over 25 years and this recent claim by China of ‘Dumping’ wine into the China market was started by Chinese wine producers and exacerbated by the corona virus statements by politicians. Chinese wine producers lost market share mainly to Australia over the past 5-6 years not caused by dumping but due to Chinese consumers having a love affair with our wines. They loved the wine styles, quality and packaging, over local wines and also over European wines. Australian producers worked very hard promoting ‘Brand Australia’ and their wines investing a lot of their own money attending trade shows, supplying samples and designing . No way were wines being dumped as most wineries I know could not afford to sell below cost!