A NEW study examining the impacts of water recovery in the southern Murray-Darling Basin has found both buybacks and on-farm efficiency programs result in higher prices.

Hypervision Creative/Shutterstock

It’s been 13 years since the Australian Government set out to develop the Murray-Darling Basin Plan with the goal of finding a more sustainable balance between irrigation and the environment.

Like much of the history of water sharing in the Murray-Darling over the last 150 years, the process has been far from smooth. However, significant progress has been achieved, with about 20% of water rights recovered from agricultural users and redirected towards environmental flows.

One of the most difficult debates has been over how the water should be recovered.

Initially most occurred via “buybacks” of water rights from farmers. While relatively fast and inexpensive, opposition to buybacks emerged due to concerns about their effects on water prices and irrigation farmers and regional communities.

This led to a new emphasis on infrastructure programs including farm upgrades in which farmers received funding to improve their irrigation systems in return for surrendering water rights.

While these farm upgrades are more expensive, it was thought that they would have fewer negative effects on farmers and communities.

However, new research from the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences finds that – while beneficial for their participants – these programs push water prices higher, placing pressure on the wider irrigation sector.

Two types of water recovery programs

The Murray-Darling Basin operates under a “cap and trade” system. Each year there is a limit on how much water can be extracted from the basin’s rivers, based on the available supply.

Water users (mostly farmers) hold rights to a share of this limit, and they can trade these rights on a market.

To date 1,230 gigalitres of these water rights have been bought from farmers via buyback programs at a cost of about A$2.6 billion.

Read more:

Drought and climate change are driving high water prices in the Murray-Darling Basin

The other type of program is farm upgrades which offer farmers funding to improve their irrigation infrastructure in return for a portion of their water rights.

To date 255 gigalitres of water has been recovered through farm upgrades at a cost of about $1 billion.

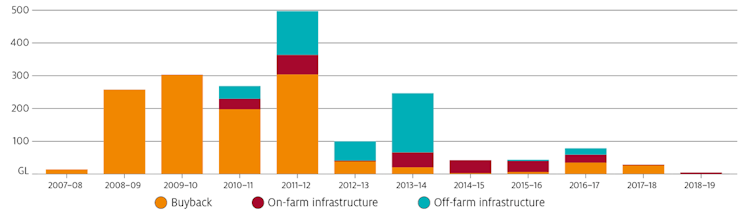

Annual volume of water rights recovered for the environment since 2007-08

Sources: Department of Agriculture Water and Environment, Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder

Water recovery has increased prices

As would be expected, the dominant short-term driver of prices is water availability, with large price increases during droughts. The dominant longer-term drivers include lower average rainfall related to climate change and the emergence of new irrigation crops including almonds.

While water recovery has played less of a role, buybacks and farm upgrades have still reduced the supply of water to farmers and increased prices to some extent.

Read more:

New study: changes in climate since 2000 have cut Australian farm profits 22%

Our modelling suggests water prices in the southern basin are around $72 per megalitre higher on average as a result of water recovery measures, with the effects varying year-to-year depending on conditions.

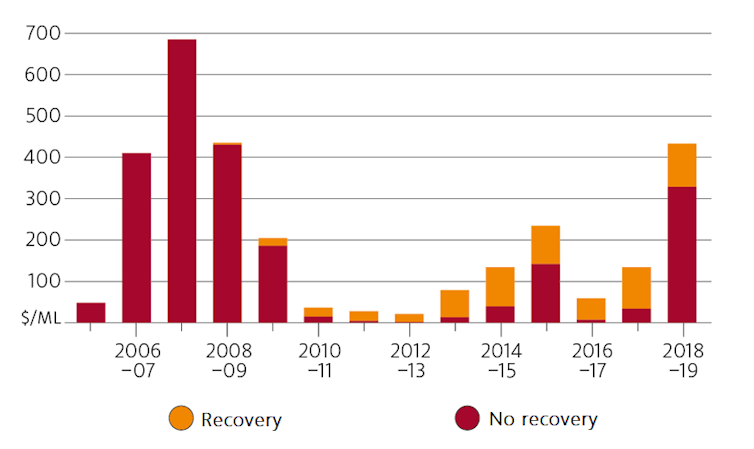

Modelled water allocation prices with and without water recovery

ABARES modelling

Farm upgrades increase prices more than buybacks

Farm upgrades are often viewed as an opportunity to save water and produce “more crop per drop”.

But they can also encourage farmers to increase their water use as they seek to make the most of their new infrastructure: sometimes referred to as a “rebound effect”.

While there have been concerns about rebound effects for some time, there has been limited evidence until recently.

As would be expected, our study finds that upgraded farms have benefited in terms of profits and productivity. However, we also find large rebound effects, with upgraded farms increasing their water use by between 10% and 50%.

To get the extra water they need to buy it from other farmers, putting pressure on prices. We find the resulting price impact to be much more than the impact of buying back water. Per unit of water recovered, it is about double that of buybacks.

These higher water prices increase the risk that irrigation assets – including some newly upgraded systems – could become stranded as price sensitive irrigation activities become less profitable.

No easy answers

Recovering water through off-farm infrastructure is one alternative, however the most effective projects have already been developed, leaving cost-effective water saving schemes harder to find.

This brings us back to buybacks. Because buybacks are cheaper than farm infrastructure programs, there is more scope to combine them with regional development investments to help offset negative impacts on communities.

The challenge is that in a connected water market the flow-on effects on water prices and farmers can be complex and difficult to predict, making it hard to know where to direct development investments.

Read more:

Billions spent on Murray-Darling water infrastructure: here’s the result

A potential middle ground is rationalisation, where parts of the water supply network are decommissioned, and affected farmers are compensated both for their water rights and for being disconnected from water supply. This approach has less effect on water prices and allows regional development initiatives to be targeted to the affected areas.

However, rationalisation can be hard to implement given it requires negotiating with all affected farmers and all levels of government.

Given the complexity of the Murray-Darling Basin, water policy is far from simple. While it is clear more water will be needed to put the basin on a sustainable footing, there are no easy options.

Further progress will require careful policy design to help ease adjustment pressure on farmers and regional communities.![]()

Authors: Neal Hughes, senior economist, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES); David Galeano, assistant secretary, natural resources, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), and Steve Hatfield-Dodds, executive director, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

HAVE YOUR SAY