Food futurist Tony Hunter addresses the PIX/AMC 2022 opening session.

WHEN Tony Hunter looks into the future he can see a world without a food industry, and not because people have stopped eating food.

It is because he says the food industry will merge into the health industry, and companies, including Nestle and Mars, are looking to ride the technology wave already carrying a plethora of businesses into the health space.

Speaking at the Poultry Information Exchange and Australasian Milling Conference, or PIX/AMC 2022, event at the Gold Coast last week, the food futurist was speaking to attendees, including representatives of the pork sector, about his TECHXpotential concept.

While it includes alternative proteins and cellular agriculture, Mr Hunter focused on the other three fields central to his concept: genomics, the human microbiome, and synthetic biology.

Animal protein and other traditional foods rated a mention only in passing, not because Mr Hunter sees their days as numbered, but because they are mature industries.

“I see there will be no food industry in 2050.”

“There’ll still be food companies but I don’t think there’ll be a food industry indistinguishable from a lot of what’s going on in the health industry.

Mr Hunter is based in Brisbane, and started out in 1987 as a technical manager for FJ Walker Foods, the supplier of hamburger patties to McDonalds.

He has worked extensively with other chains including Burger King, and got involved in food futurism in 2017 when he started to notice a “real uptake in new technology”.

“This is the most exciting time to be in the food industry that I’ve seen in 30 years.”

Mr Hunter said perceptions about the role of food were already changing.

“People eat not just for fuel…but for their wellness.”

“But as people eat for their health, then what industry are food companies in? They’re in the health industry.”

Icelandic molecular farmer ORF Genetics is growing barley grain to produce recombinant human and animal proteins. Photo: ORF genetics

The Nestlé Wellness Ambassador program, which incorporates DNA testing, AI and food on social media, is in its pilot phase in Japan, and Mars Group’s purchase in 2019 of Foodspring, a German-based targeted nutrition company.

Irish-based multinational ingredients manufacturer Kerry now also offers ProActive Health wellness ingredients range.

Mr Hunter said these corporate moves are among many that show that technology is able to influence diets on a personal level, and uptake is already happening.

And while the world’s Gen Z population has witnessed the introduction of digital technology into everyday life, Mr Hunter said Gen Alpha has been born into the digital era.

“They are far more likely to accept technology in their food.”

Science influences food choices

Mr Hunter spoke about some of the companies around the world at the forefront of bringing science into the shaping of diets and the making of food.

On the genomics front is DnaNudge, a London-based company which can analyse a person’s cheek swab and translate it into personalised nutrition advice.

Also from the United Kingdom is Atlas Biomed, where DNA is used to determine personalised disease risks, predisposition to food intolerances, and dietary recommendations.

“This is what we call as futurists a signal.”

Mr Hunter said the uptake of DNA analysis is likely to work its way into more than the home kitchen, and platforms like UK-based restaurant ordering and management platform Vita Mojo could well be the vehicle.

“I don’t think food service will be immune to the effects of DNA analysis.”

Mr Hunter said personalised reactions to blood sugar through companies like the US’ Day Two are also in the equation, as are personalised probiotics which add bacteria and fungi to improve gut and overall health.

Brisbane’s Microba is a leading researcher in this field, and Mr Hunter said he could see personalised biome profiles becoming par for the course.

“It will become as common as DNA in years to come.”

With personalisation already rife in our digital lives through platforms like Spotify, Google, and Netflix, Mr Hunter said its ability to reach into diets can easily be seen.

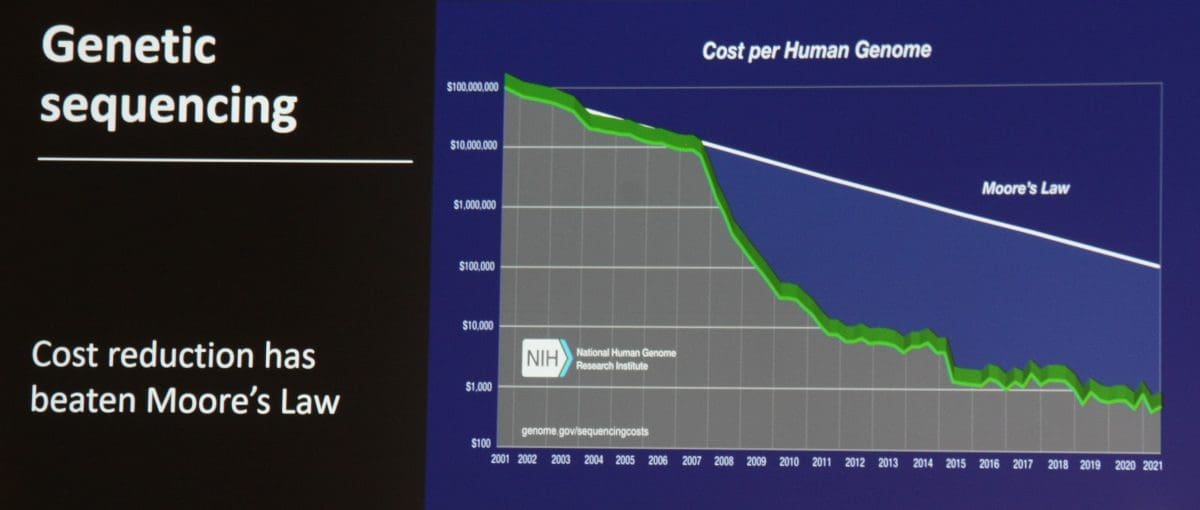

Food futurist Tony Hunter said the cost of genetic sequencing has fallen sharply, which is encouraging the use of genomics in the formulation of personalised human diets. Image: National Human Genome Research Institute

Synthetics broaden

In the food-manufacturing space, Mr Hunter said there were already examples aplenty of synthetic biology, which involves taking the gene for a product you want to make, inserting it into another living organism, and getting it to make that product.

“The best example of this is cheese.”

Mr Hunter said Pfizer in 1990 developed a substitute for rennet which occurs naturally in calf stomachs by putting the gene for chymosin, rennet’s primary enzyme, into a microorganism to produce more chymosin.

This genetically modified product is now used to set 80-90 per cent of the world’s hard cheeses.

With similar technology, Perfect Day, with bases in the US and India, has been using technology to make animal-free whey protein, some of which is used by US dairy-free milk producer betterland.

Beyond the dairy space, EVERY, with backing from US-based global food giant Ingredion, is making egg white-type proteins.

Iceland’s ORF genetics, which is using bioengineered barley to make growth factors for cell-cultured meat and other products, is another example.

Mr Hunter said Nobell Foods had put the gene for casein into soybeans as an example of plant molecular farming, where plants are being used as bioreactors.

“Their products will be on the market next year; another science fact, not science fiction.”

Hunter came up with some startling images in his presentation of where food in the future is headed.

One comes from SavorEat, in conjunction with the BBB burger chain in Israel, which employs a 3D printing and cooking robot to manufacture food within six minutes to customer-determined levels of protein, fat and other metrics.

Grain Central: Get our cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY