TWO years ago we were celebrating just about the best year for farmers ever. Now many farmers – particularly in New South Wales and southern Queensland – are in the grip of drought.

It underlines just how variable the Australian climate can be.

While attention is focused on responding to the current situation, it is important to also think long-term. In our rush to help, we need to make sure well-meaning responses don’t do more harm than good.

The drought policy debate

The recent drought has stimulated much empathy for farmers from the media, governments and the public. Federal and state governments have committed hundreds of millions of dollars in farmer support. Private citizens and companies have also given generously to the cause.

While there appears to be overwhelming public support for helping farmers through drought, concerns have been raised by economists as well as farmer representatives – including both the former and current head of the National Farmers’ Federation.

A central concern is that drought support could undermine farmer preparedness for future droughts and longer-term adaptation to climate change.

Another concern is that simplistic “farmer as a victim” narrative presented by parts of the media overstate the number of farmers suffering hardship and understates the truth that most prepare for and manage drought without assistance.

Sensationalist media coverage can also damage Australia’s reputation as a reliable food producer. Images of barren landscapes, stressed livestock and desperate farmers send the wrong signals to customers and trading partners.

An acute policy dilemma

The tension in drought policy is real.

To remain internationally competitive Australian farmers need to increase their productivity.

Agricultural productivity depends on two main factors. First, innovation – adopting new technologies and management practices. Second, structural adjustment – shifting resources towards the most productive sectors and most efficient farmers.

Supporting drought-affected farms has the potential to slow both these processes, weakening productivity growth.

This gives rise to an acute dilemma: should we support farmers in distress, or support the industry to be the best it can be?

Read more:

To help drought-affected farmers, we need to support them in good times as well as bad

Factoring in climate change

While it is difficult to attribute any specific event to climate change, it is clear Australia’s climate is changing, with significant consequences for agriculture.

Australian average temperatures have increased by about 1℃ since 1950. Extreme heat events have become more frequent and intense. Recent decades show a trend towards lower average winter rainfall in the southwest and southeast.

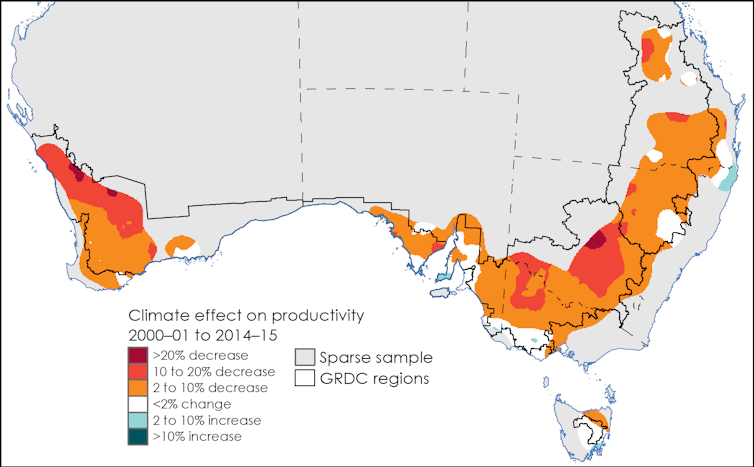

Research by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences shows climate change has negatively affected the productivity of cropping farms, particularly in southern Australia.

This research also shows evidence of farmers adapting to maintain productivity and reduce their sensitivity to climate.

ABARES

There is still much uncertainty over what climate change will mean for agriculture in the future.

However, the evidence we do have points to more frequent and more severe droughts, if only because of higher temperatures and evaporation rates.

Farming isn’t like other industries

Although businesses in other industries are expected to manage risk without assistance, agriculture has some special aspects that help build a case for a government policy response.

First, risk in agriculture is generally greater than in other industries. Farmers are vulnerable to variation in international commodity prices as well as droughts and other extreme events.

Second, most farm businesses are also farm households.

While many other risky industries are made up of large corporate businesses (generally with diversified assets and ownership), agriculture is dominated by family farms.

Third, financial markets both in Australia and internationally struggle to provide viable risk management products for farmers – particularly drought insurance.

This means farming is an unusually risky business. Farmers must therefore be more conservative about financing and operating their businesses, which constrains investment, innovation and ultimately productivity.

Helping farms without making things worse

In 2008 a Productivity Commission review recommended a national farm income support scheme.

This led to the Farm Household Allowance program.

It provides a fortnightly payment, usually set at the rate of the Newstart unemployment allowance. There is also a financial assessment of the farm business and funding to help develop skills or get professional advice.

Those welfare programs provide an important safety net for farm households. Because they provide targeted support to households, rather than businesses, they result in fewer economic distortions than alternative approaches.

Past reviews have consistently recommended against subsidising farm business inputs or supporting output prices. This includes providing subsidies for livestock feed.

While these measures might provide short term relief, if they become routine they risk weakening the incentives to manage farms properly, by for instance destocking sheep and cattle ahead of likely droughts.

Read more:

Drought is inevitable, Mr Joyce

Looking to the future, it is possible insurance could have an important role to play.

While drought insurance has failed to thrive in Australia to date, advances in data could allow more viable forms of insurance to emerge.

In particular, index-based insurance products where payouts are based on weather data rather than an assessment of farm damages.

Such insurance, if done well, could provide farmers with better protection from climate risk, while also supporting adaptation and productivity growth – effectively sidestepping our current drought policy dilemma.![]()

………………..

Neal Hughes, senior economist, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) and Steve Hatfield-Dodds, executive director, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

HAVE YOUR SAY