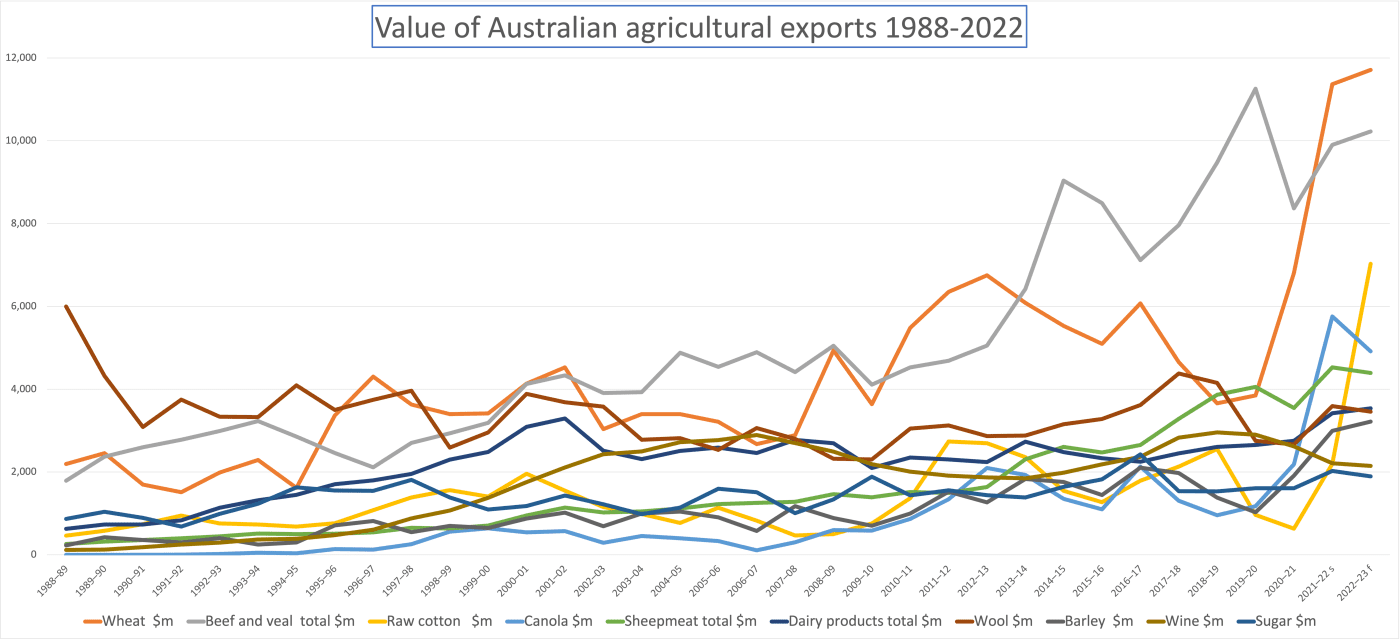

Had you answered beef you would have been correct for most of the past decade.

However, lower prices for red meat and a rise in wheat prices fuelled by a global shortage, along with higher Australian production, has resulted in wheat surging to become Australia’s highest value agricultural export for the past two years in a row.

The value of financial year exports of Australian wheat is forecast to reach $11.7 billion in 2022–23 – which would be the second-highest on record – and above forecast beef export value of $10.2 billion.

The Australian wheat indicator price (Australian Premium White) is forecast to increase in 2022–23 to an average of $520 per tonne, reflecting high world prices. Ample export supply and competitively priced Australian wheat has also allowed Australian exporters to increase market share in key markets, reflected by robust demand from China, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

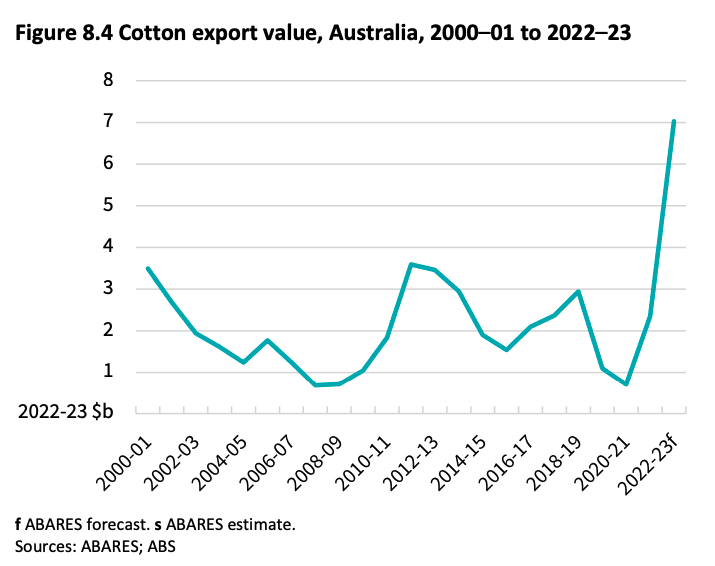

Cotton threads its way to third most valuable ag export

The value of cotton exports is forecast to reach a record $7 billion in 2022–23, which includes production grown in 2021-22 but which will not be shipped until 2022-23. This forecast puts cotton on track to become Australia’s third most valuable export commodity after wheat and beef – the highest ranking for cotton on record (since 1988).

Record farm incomes, but higher costs

Average farm incomes in 2021–22 are projected to be the highest on record at an average $278,000 per farm. However, ABARES notes the cost of food and fertiliser remains very high worldwide, with urea prices now three times higher than average. The fact that urea imports to Australia have not slowed despite this shows that fertiliser supplies are likely to be sufficient for the 2022-23 season, but higher costs will erode farm margins. “As flagged in ABARES 2021–22 farm survey results, higher input costs did affect farm incomes, and the full effect of higher fertiliser costs is likely to be felt in farm returns for 2022–23.”

Global growth has been downgraded

ABARES attributes this largely to inflation – driven by high energy prices as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and COVID-related disruptions – and slowing Chinese growth. Inflation is expected to remain “relatively high” throughout 2022–23.

Global supply chains remain under pressure, but there are signs of improvement

Spot prices for container freight on major shipping routes were around 40 percent lower at the start of August 2022 than they were in August 2021. This reflected falling demand for shipping following a period of inventory restocking by importing businesses and lockdowns in China which reduced exports. Over 2022–23, supply chain disruptions are expected to continue to ease, ABARES predicts.

The Australian dollar is assumed to depreciate to US70 cents in 2022–23.

That compares to US73 cents in 2021–22.

Herd and flock numbers are forecast to recover to pre-drought levels by the end of 2022–23.

A third straight La Niña event forecast for late 2022 is now the climate model consensus – roughly a once-every-30-years event. Good for national production prospects, but this could result in significant local impacts such as flooding, livestock losses, and quality downgrades for crops.

Suit slip signifies shifting consumption habits

One more sign of our changing times. Sales of traditional wool suits have been declining, a trend attributed to the relaxation of work dress codes and professionals increasingly working from home. The United Kingdom’s Office of National Statistics has just officially dropped men’s suits from its basket of more than 700 items used to determine inflation. The suit, which has been in the basket since inflation tracking began (1947), has been replaced with “men’s formal jacket/blazer”, signifying shifting consumption habits.

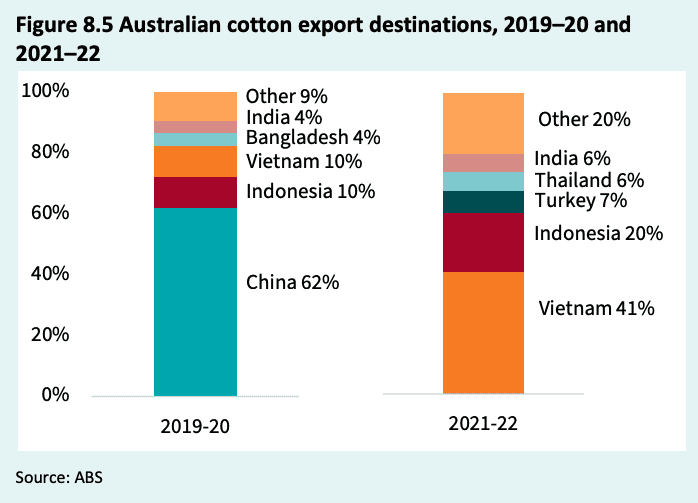

A dramatic diversification of Australian cotton destinations

Not only have Australian cotton exports surged by 128 percent in just three years, the destination profile has also changed dramatically. In 2019-20, 62 percent of Australian cotton exports went to China. However, following reports in October 2020 that Chinese cotton importers were being advised not to use quota allocation on Australian cotton, Australian exporters successfully diversified, indicated by 2021-22 export figures: the majority of Australian cotton exports went to Vietnam (41pc), Indonesia (20pc), followed by India (7pc), Thailand (6pc) and Turkey (6pc), with China well down the list along with several other destinations.

Average saleyard cattle prices are forecast to fall 13 percent to 727c/kg in 2022-23 (down from a record-breaking year with an 820c/kg average in 2021-22), due to easing restocking demand.

However, two factors could buck the forecast: Firstly, the US cattle herd is being liquidated due to dry conditions and the high cost of feed. Should the outlook for seasonal conditions change and support herd rebuilding before the end of the forecasting period, global cattle prices will also rise as the US retains cattle and their production volumes fall. Secondly, just as Australia saw spending rebound post-covid lockdowns, an end to China’s lockdowns could see the country buy more beef from world markets, pushing up prices.

Sheep saleyard prices are expected to fall, but remain historically high

ABARES forecasts a 16pc drop in average prices to 700c/kg in 2022-23. Strong international demand for Australian sheep meat is expected to sustain high saleyard demand for finished animals, but demand from graziers for restocking animals is expected to fall.

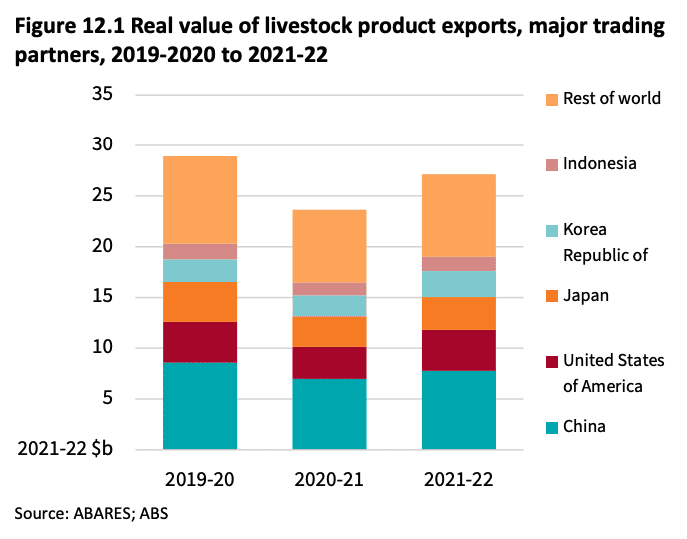

How long would it take for Australia to regain access to export markets, if an outbreak of FMD was confirmed here?

An ABARES article in the latest outlook report notes that the most significant financial costs to the Australian agricultural sector would be the result of losing access to overseas markets. Factors including how widely an outbreak spreads and the measures Australia employs to contain and eradicate it would be critical in determining how long market access is lost. ABARES notes that the World Organisation for Animal Health (which provides guidance for safe international trade in livestock and livestock products) would, at a minimum, require three months from the disposal of the last animal killed using a “stamping out” policy without vaccination, and an application to demonstrate appropriate steps have been taken to eradicate, monitor, and protect from further incursion. Separate to gaining clearance from WOAH, Australia would still need to negotiate regaining of market access with its trading partners. As a guide, ABARES says, history shows that even if an FMD outbreak is controlled quickly (such as in the case of Ireland which was within 2 days), the fastest anticipated FMD freedom recognition by a trading partner (the United States as an example) was 228 days. The longest time taken to recommence trade after an outbreak was in Japan, where trade to the United States did not recommence for 774 days.

And how would livestock prices in Australia react to an FMD outbreak?

It makes for grim reading but ABARES also offers some guidance on what producers might expect to happen to the value of their livestock in response to an FMD incursion. Given that Australia exports most of its livestock products, even in the case of a small, localised outbreak, if all the beef normally destined for export markets was diverted domestically, it would represent an increase of 270 percent in the volume of beef on the local market. The result is likely to be a substantial fall in the domestic farmgate price of livestock and the retail price of meat over the first few months of an outbreak. Prices could fluctuate rapidly and change as participants in the supply chain adjust their production decisions. After the price shock in the first few months, and once producers had started to respond to the oversupply, the domestic price would be expected to increase from the low resulting from the shock. While the price would increase, it would still remain below what it would have otherwise been with no incursion. ABARES modelling from 2013 modelled two small outbreak scenarios which estimated that 12 months after the incursion the price to be 12-16 percent lower than it would have been otherwise, “under relatively favourable timelines for restored market access”. Wool would also be affected by export market access issues, as it is largely sold into international markets. Wool producers would have to consider storing wool until access to international markets are restored.

To view the full ABARES September Quarter Agricultural Commodities report here

HAVE YOUR SAY