FERTILISER is a vital input cost for Australian farmers. It is important to shine a light on pricing to assist in making purchasing decisions.

The majority of farmers purchase their fertiliser in the first quarter of the year. Unfortunately, this year this has coincided with a very strong rally in pricing levels.

The majority of farmers purchase their fertiliser in the first quarter of the year. Unfortunately, this year this has coincided with a very strong rally in pricing levels.

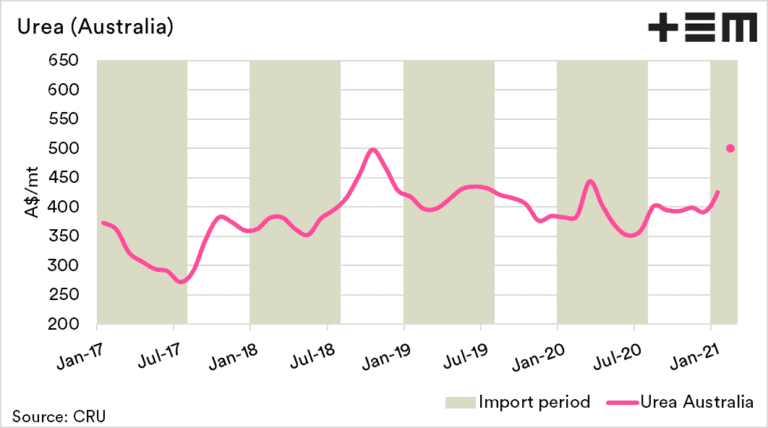

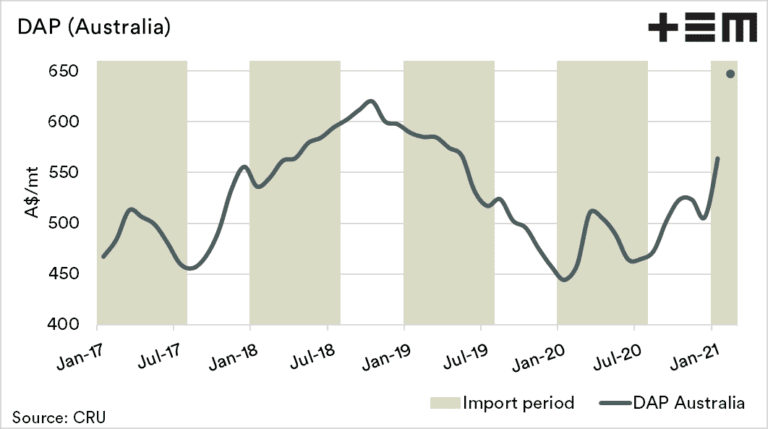

The charts below show the fertiliser cost at the origin, plus the average monthly cost of freight to Australia converted to Australian dollars. The sources are Saudi Arabia for Urea, and China for DAP. These are where the bulk of Australian fertilisers originate.

These charts give an idea of the trend, and there will be a degree of variability between these prices and what you pay. These include additional local logistics, administration and retailing costs

Many factors influence fertiliser prices, including the cost of other commodities (energy). Still, these charts should inform on the general trend.

Whilst we are only into the second week of the month, the rise so far in February has been quite stratospheric.

The average theoretical price landed for DAP was A$564 in January, but recent numbers show that it has jumped to A$647. The Urea price has increased during the same period from A$425 to A$500. The recent rise is substantial, and one which unfortunately coincides with our buying period.

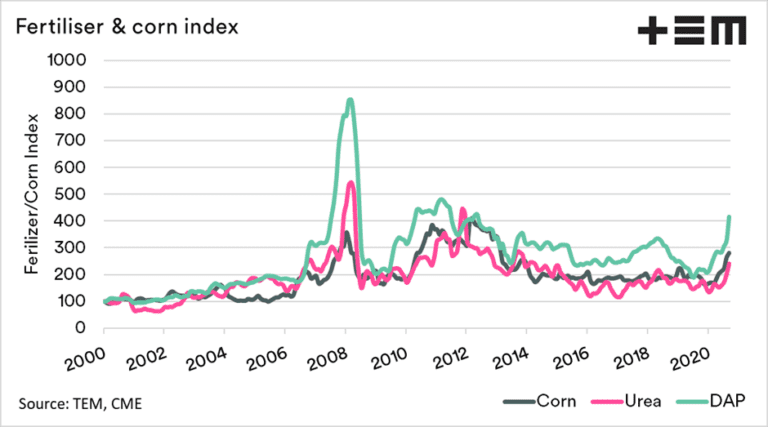

The cost of energy has increased in recent months after the lows of 2020, at the same time, demand has been rising with higher grain pricing. Figure 3 shows a long term index of corn, urea and DAP.

We can see that fertiliser and corn pricing tends to follow a relatively similar pattern. This is potentially a sign that as grain prices rise, so do fertiliser prices.

Fuel pricing

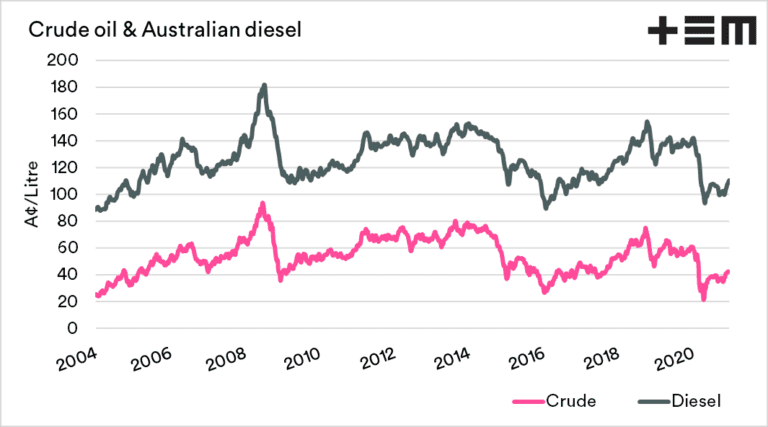

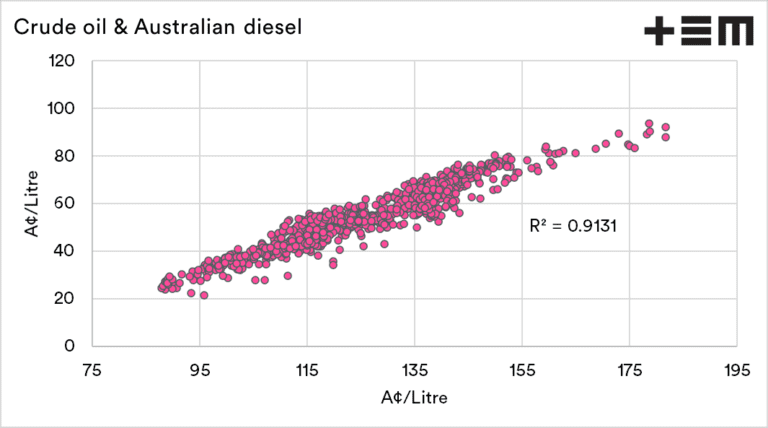

As we approach seeding, one of the significant costs will be fuel. The biggest driver of fuel pricing is crude oil. This makes sense as diesel is derived from crude. Crude oil futures and Australian diesel pricing has a correlation of 0.91, with 1 being perfect and 0 being no correlation.

This means that if crude oil prices rise, our prices should follow (and vice versa). Due to the high correlation between the two, it would be possible to use crude oil futures as a hedge against fuel usage. There are institutions which offer this service. The reality, however, is that most have very high minimal levels.

The crude oil market collapsed during 2020, as large tracts of economies shut down. The crude oil market has from lows of US$19 per barrel, in recent weeks crude has been grinding higher to settle above US$60 per barrel.

Whilst diesel prices in Australia have increased in recent months in line with moves overseas; the reality is that prices are remaining at low levels compared to most of the past decade.

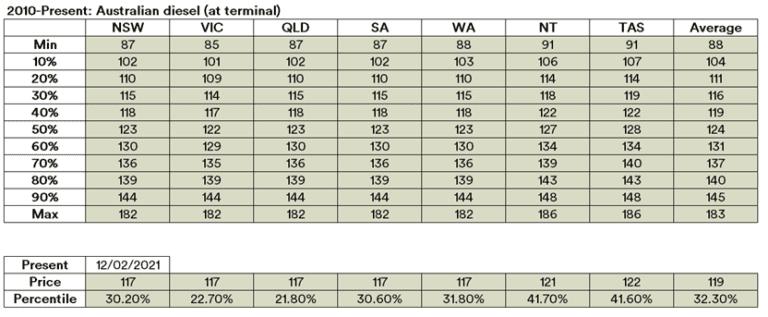

The decile table below displays where current prices sit compared to the timeframe 2010 to present.

A decile measures how often, historically, prices have fallen below (or below) a particular pricing point. It gives a brief snapshot of whether a market has more upside or downside and how large this may be.

For example, if a price is at its 45th decile, 45 per cent of the time prices have been below that value and 55pc of prices higher. Similarly, a 99pc percentile means that 99pc of the time, prices have been lower and higher just 1pc of the time.

The interesting point from this data is that most states are in line between 20-30th decile, except the Northern Territory and Tasmania, which are paying considerably more than the other states.

This article was originally published on the Thomas Elder Markets website: https://www.thomaseldermarkets.com.au/

View original articles: Fertiliser pricing and Fuel pricing

Listen to Matt Dalgleish and Andrew Whitelaw chatting with Chris Lawson (CRU) on their personal podcast ‘Ag Watchers‘ about the fertiliser market back in November. In this podcast, Chris discussed the possibility of higher fertiliser prices in the first half of 2021.

HAVE YOUR SAY