WHEN John Cameron took up his first job as product development research officer with Monsanto at Emerald in Central Queensland (CQ) in the early 1980s the region was losing around 20 tonnes/hectare of soil each year to the ravages of erosion.

John Cameron

It was a time when the established farming practice was to run multiple cultivations to suppress weeds and prepare fine-tilth seedbeds – a system that ultimately led to soil structural issues and exposed the landscape to high erosion risk.

In concert with other agricultural leaders in CQ, including recently-retired agricultural consultant, Graham Spackman, Mr Cameron set about the challenge of encouraging the region’s farmers to change their farming systems over to zero-till regimes.

Today, the sloping farming country of CQ is largely farmed by stubble-retaining, moisture-conserving, no-till systems that have increased soil water retention, created greater cropping opportunities and delivered more consistent levels of ground cover which have helped alleviate the erosion issues.

Mr Cameron’s early years in CQ were one of the many hallmarks of a career that saw him move to Moree in north west New South Wales in 1985 to take up roles in research and dryland agronomy consulting, then on to Sydney in 1989 to work with agricultural chemical companies in broadacre cropping and cotton.

It was in 1995 that he took the bold decision to branch out and found the agronomy and communications business, Independent Consultants Australia Network (ICAN), which has, for nearly quarter of a century, stamped its mark as the key provider of the Grains Research and Development Corporation’s (GRDC) suite of research updates throughout the northern growing region.

Driving the no-till revolution

Born and raised in Victoria, Mr Cameron completed an agricultural science honours degree at Melbourne University before taking up his first appointment with Monsanto in CQ.

“My brief was to do whatever was necessary to get no-till running in CQ. I worked as closely as I could with agronomists and soil conservation guys,” he said.

“The country was still being opened up at 50,000 hectares a year in those days. I recall vividly the 1982 drought and 1983 flood. The rain of the 1983 flood started on the same day as the Emerald B&S recovery. We had about 200 inebriated youth in town for the next four weeks as you couldn’t go north, south, east or west.”

Mr Cameron said the driving force behind the adoption of no-till farming in CQ was the need to contain the soil erosion problem that was rampant throughout the area at the time.

“Cover was and is king. You just have to have sufficient crops to generate soil cover to capture water efficiently and make it available for the next crop, particularly in the high intensity summer storm environments in Central Queensland,” he said.

Mr Cameron said in the early 1980s one of the challenges of convincing growers to adopt the new system of farming was that it required a massive change in thinking away from established practices.

“People would tell you: “You have to aerate the soil, mate”. That was a big thing. So, it was an intergenerational change for people to change the farming system and trust it could be done,” he said.

“It often meant not only management change but machinery change. One of the other impediments was the cost of glyphosate back then. That reduced over time.

“The other major change was tramlining. We really needed the massive technology shift that was afforded by self-steer tractors and GPS positioning to enable farmers to accurately map in the paddock and not over spray or under spray and leave massive gaps. That has been a huge enabling technology for no-till.”

Mr Cameron, said no-till ultimately became a huge success story, not only in CQ but throughout Australia, because conservation methodologies and responsible resource management methodologies married with high production outcomes.

“We have increased the width and time of sowing windows, we have increased rain capture, water use efficiency and yield. It has ticked all the boxes while protecting the resource base,” he said.

Dispelling the myth ‘You have to aerate the soil, mate’. Soil conservation officer Monty Gilmore inspects the first no till crop grown in CQ in 1981. Standing is grower Terry Promnitz (Retro and Weibmy Downs, CQ). “Terry called me on a Sunday morning and said that the trial had emerged. I was so excited that I went straight to pick up Monty where we discussed taking champagne to celebrate with in the paddock.” (Photo: John Cameron)

Farming challenges ahead

Looking ahead, Mr Cameron said Australia’s farming sector faced challenges on a number of fronts.

“One is herbicide resistance and our ability to efficiently sustain the system that now underpins farming across the country,” he said.

“Australia is a dry climate and we are absolutely reliant on our ability to capture water, moreso than most climates, so climate change and temperature changes are going to make it a lot harder for us than they are for some of our competitors.”

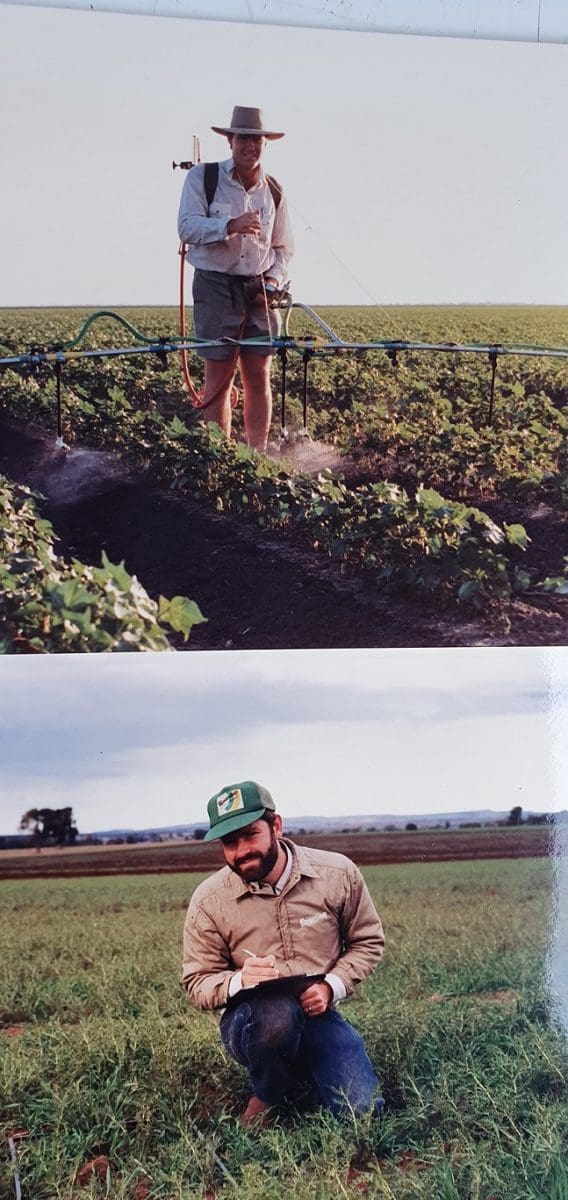

(Top) John Cameron spraying a cotton trial at Moree in 1987. (Bottom) Checking a trial in one of the early chickpea crops near Moree in 1985.

Mr Cameron said another looming challenge related to soil carbon levels and plant nutrient supply.

“I see a storm coming with the issues we are seeing with climate change, coupled with a lot of the free lunches from nitrogen available through soil organic carbon that are now used and gone,” he said.

“Organic carbon, particularly with the profile of release that it had, really buffered our systems for nitrogen demand across a range of outcomes. We have lost a lot of that nitrogen buffering capacity.

“At the same time, we are starting to see widespread need for phosphate fertilisers, particularly deep applied P in the northern region.

“That’s concerning when you couple those two things with the greater difficulty of sustaining fallow efficiency through good weed control due to herbicide resistance or the increasing dominance of weeds that are hard to kill with the current suite of herbicides.

“That poses an enormous challenge for the next generation of researchers, agronomists and farmers.”

Precision ag adoption

Mr Cameron said Australian farmers had been at the forefront of applying some of the latest precision and automation technologies, but had been slow to take up others.

“In the short to medium term we have seen rapid adoption of global positioning for driving tractors and precision placement of seeds. The adoption of GPS-based systems has made the apparent size of paddocks shrink which has meant massive savings on input costs and efficiencies,” he said.

“At the same time, we have seen a lack of adoption of some of the more data-driven processes that see more variable rate approaches.

“There are some early adopters who have been mapping soil and yields for years and putting the two together to fertilise with higher rates where there are deeper soils and higher yield expectations. That makes a lot of sense.

“But, across the board, the percentage of land area that is taking up those variable rate challenges has been below expectations.”

Mr Cameron said from studies on what drove adoption, one of the outcomes was that if there are no barriers to technology adoption and a big bottom line benefit there was massive early adoption.

But as you start winding back either the bottom line benefit or increased the barriers to adoption, although there might still be significant profitability, adoption levels declined.

“That seems to have been the case with some of the more advanced aspects of variable rate technology at this point,” he said.

“An impediment has been the low speed of data transfer speed in Australia, which I think that may be part of the answer, but also part of the excuse, to explain the lower levels of adoption.”

Ag communications specialist

In establishing ICAN in 1995, Mr Cameron saw the opportunity to pitch a proposal to the GRDC for a more streamlined and structured system of relaying research findings to the wider agricultural communities.

The GRDC accepted the proposal and the successful formula of the now widely-attended GRDC updates was born.

The program started with five, one-day updates targeted at agronomists in the northern region and expanded the next year to both agronomist- and grower-targeted updates.

Today, the updates are a high-priority fixture on the calendars of agronomists and farmers throughout the north.

Mr Cameron has become the widely-recognised figure at the helm, using his skills as a grains communications specialist to bridge the gap between industry research developments and on-farm adoption.

“There is all this money spent on generating good information and data and our key conduit to get this to the grower networks is via the agronomists who are working hand in hand with those individuals on a paddock by paddock basis,” he said.

“Everyone is in information overload, so it is a real filtering job. Their role is to filter which information is appropriate to their growers and to help those growers implement profitable outcomes on their properties.”

John Cameron running this year’s GRDC updates by webinar due to COVID-19 restrictions.

COVID forces switch to webinars

With COVID-19 restrictions coming into force in 2020, Mr Cameron said the updates program in the latter half of this year was too difficult to run as face-to-face events, so the decision was made to run them all as webinars.

“We selected a subset of 23 issues to run as webinars to replace the nine updates held at venues throughout NSW and Queensland,” he said.

“Given the success of the webinar format, we now have a subset of people who, for a range of reasons, don’t come to the live updates. So, the plan for next year is to keep the live updates first and foremost, but out of the 16 one-day updates next year we are going to drop two of those and use that budget to run a number of webinars.”

Mr Cameron said he expected to still be operating in a COVID-19 environment into the first half of next year, so the three, major, two-day updates scheduled for Wagga Wagga, Dubbo and Goondiwindi would be conducted under a revised format.

“We will be running a two-day agenda at Dubbo and Wagga Wagga, but instead of having multiple concurrent sessions with people moving around we will try to minimise movement by running one general plenary session. There will be two separate cohorts of growers and agronomists at those venues,” he said.

“Because Goondiwindi is on the NSW-Queensland border, there is still the risk of border closure, so we have cancelled the Goondiwindi update and, instead, will run two, one-day updates at Narrabri in northern NSW and Dalby in southern Queensland. The rest of the one-day updates scheduled are going ahead as normal.”

Mr Cameron is a fellow of the Australian Institute of Agriculture and the 2011 recipient of the GRDC Seed of Light Award.

In his spare time he enjoys getting away from it all through his passion for hiking and fishing.

John Cameron and his wife, Robin, hiking in the Western Arthurs region of south west Tasmania in 2006.

Grain Central: Get our free cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY