The 466ha North Avoca between Narrabri and Boggabri is for sale for $1.9M, and is currently leased until 30 March 2021 for $80,000 plus GST per annum to deliver a return on investment of around 4pc. Photo: Rural Property NSW

INTEREST on both sides of cropping-land lease agreements is steady to strong as demand continues to exceed supply in the property market, according to agents and Rabobank analyst Wes Lefroy.

Rabobank’s A New Lease on Land report released on 10 February said leasing was set to become increasingly common in the Australian agricultural sector, and its author, Mr Lefroy said economic uncertainty brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic has boosted its popularity further.

Speaking to Grain Central last week, Mr Lefroy said COVID-19 has highlighted the value of agricultural land as an investment class, and this has encouraged lessors to retain or expand area.

On the lessee side, operators are seeking more area to farm as confidence in agriculture remains buoyant amid limited numbers of properties being offered for sale.

The report was released before COVID blindsided the global economy.

“The performance of ag through COVID has shown how resilient it is.”

“Ultimately, the number of properties on the market will remain low, and during COVID, we’ve seen different ways of buying them as farm business models diversify.”

Analysts and agents have said these became more common after the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry released its findings last year.

It tightened the parameters on operational and property lending, and the knock-on effects of COVID have further slowed approvals, and encouraged some wishing to buy cropping land to instead consider leasing or adopt a non-traditional business model.

The report said these models include sale and lease-back, or equity partnerships.

Leasing expands scale

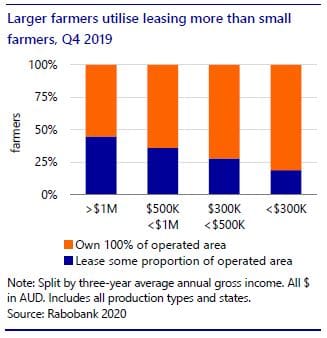

Mr Lefroy said 45 per cent of farmers surveyed with a three-year average annual gross income of greater than $1M were leasing some country.

“Large farmers are using it to expand, and we’ve seen that with grain.”

Rabobank’s latest research indicates 28pc of Australian farmers leased some of their operated area.

Of those, 11pc last year increased the area of land they leased.

“Over the next two years, we see the motivation for both current and prospective tenants and landlords to lease to become even stronger.”

Most popular in SA, WA

The report said the percentage of farmers currently operating leased land varied considerably, with differences primarily driven by structural factors like farm size and production type, and market dynamics, such as price growth and property availability.

“Leasing is more common in South Australia and Western Australia, where there are many large grain producers.”

Rabobank’s research showed 45pc of farmers in SA and 38pc in WA leased some area of land they operate.

“This is in contrast to New South Wales, where a greater proportion of livestock producers are located, and only 17pc of farmers lease land.”

Tight supply to continue

Mr Lefroy said the number of agricultural properties offered for sale in Australia had fallen by 40-50pc in all states from 2014 to 2018.

“While we expect the number of properties on the market to increase slightly in 2020, it will remain near historically low levels,” he said.

“Farmers looking to expand may be forced to turn to leasing, unable to buy the right property at the right price.”

The report predicts an increase in the amount of Australian agricultural land that will be available for lease, driven by improved investment returns and an acceleration of farmers retiring from the industry.

“We expect capital appreciation of ag land to remain healthy across many regions in Australia over the next three years, while it is also not as volatile as a number of other assets, which is valued by investors.”

Rural Bank’s Australian Farmland Values 2020 report said national farmland values rose 13.5pc over 2019.

Appeal for lessors

Ray White Condobolin partner Paddy Ward said interest in leasing country in central NSW was “huge” at present.

“People can get 4pc or better on the value of what they think their farm is worth, so if it’s worth $1M value, they can lease it for around $45,000 per annum.

“It’s better than interest rates, and a lot of people who are ready to retire are leasing their places out.

“We’ve seen a huge surge from young people wanting to lease because they’re not able to buy.”

While lessors and lessees within a district can generally find each other independently, Mr Ward said agents played a role in fielding interest from those from away.

Plains, outer slopes in demand

Temora agency Miller and James has around $190 million worth of property under management in NSW, Queensland and Western Australia, including $20M added this year to date.

Lessors on the books come from a client base split between those looking to retain ownership of the farm without farming it, and high net worth investors.

Miller and James director Angus McLaren said lower-rainfall cropping country was in greatest demand in the lead-up to the planting of this year’s winter crop.

“Leasing doesn’t seem to work so well in higher-rainfall country because there’s a lower return on investment.”

Mr McLaren said while more expensive land in higher-rainfall sheep country including the inner slopes and tablelands of NSW returned around 3pc per annum, 5pc had been achievable as a return on investment in most Australian cropping regions until recent years.

“You can still get that in WA, but now it’s more like 4-4.5pc in NSW.”

Mr McLaren said COVID had made investors keener than ever to own a real asset in their portfolio.

“When shares and currency values were falling when COVID hit and everyone thought the world was going to hell in a billy cart, agricultural investments didn’t register a blip.”

“People have become nervous about financial products.

Mr McLaren said plenty of farmers in the wider district cropped their own country, and leased some area from those wishing to step away from farming to retire, or to restructure a family partnership.

“There can be succession-planning issues, like parents wanting to buy a place in town to live in, or a sibling needing to be paid out.

“Leasing country out can provide the money for those things to happen.”

“If you can’t own country, leasing it is the second-best option.”

Lease terms important

Wagga Wagga consultancy Holmes Sackett runs courses across Australia about leasing farms, and director John Francis said leasing provided entrants to agriculture with a low-cost alternative to purchasing.

Holmes Sackett director John Francis

“Given the value of land is high, anything that gives them a chance to get in is worthwhile.”

The downside for lessees is they miss out on capital growth, and shoulder all the volatility of seasons and fluctuations in commodity prices.

Mr Francis said if the nominal value of a farm was $1M, around 80pc would be land, and the balance plant and equpiment.

Therefore, a lease rate of 4pc on an $800,000 land asset can earn $32,000 in annual lease payments.

“The long-term average for farmers cropping their own places is 3pc for good farmers, and 2pc for others, and net 2pc is on par with cash.”

“The value of leasing is leveraging.”

He said an operators leasing 1000ha of country with an overhead cost of $200 per hectare might only incur an extra $20/ha on leasing an extra 200ha.

“The marginal benefit is $180/ha, and that flows straight through to bottom line.

“The value of expanding leased area with existing assets and additional scale gives you benefits at very low additional cost.”

The flipside is it can expose you to additional risk, and Mr Francis said lessees needed to consider worst-case scenarios, such as one or more terrible growing seasons, and low commodity prices.

“The longer the term of the lease, the more likely you are to be able to claw back the impact of a bad year.”

Mr Francis said landowners needed to make sure the cost of the lease included farm overheads like rates and capital improvements and specified responsibilities for tasks like road maintenance.

“Leases can go bad; if you go in with a naïve manner, you’ll be disappointed.”

He said landowners should consider preparing an Information Memorandum that included fertiliser, soil amelioration and cropping history by paddock if they wanted the lessee to continue inputs to a certain standard.

He said corporates which owned land to lease “invested heavily in terms and conditions”.

Consider options, timing

Capital growth on cropping land has traditional been 6-7pc per annum over the long term, and Mr Francis said figures of around 17pc seen recently have been “exceptional”.

“The big question is: Can it continue?

“Money’s so cheap at the moment, and a lot more people are more interested in purchasing, so you might say: ‘I won’t lease a bigger area, but I’ll purchase a smaller area because I get operating return as well as capital growth’.”

Mr Francis said those looking for country to lease should be working towards it the year before.

“If weed control hasn’t been dealt with, or if soil amelioration is needed, there might be a cost to you as the leaseholder if you get in in January.”

He said farm owners living on site and coming out of financially difficult years can buy themselves some time by leasing the farm.

“If the bank is breathing down your neck, that’s a reasonable way to go if you don’t have the capital to roll the dice again.”

Place for sharefarming

Sharefarming has provided many a leg-up to young farmers building up capital to buy their own places, and is more popular in some districts than others.

Mr Francis said sharefarming can provide returns equivalent to leasing.

The model can vary widely, with everything from a 50/50 split in costs and income-sharing for the landowner and the sharefarmer, to the sharefarmer getting 80pc and the landowner 20pc of grain proceeds if the sharefarmer buys all cropping inputs and provides all plant and labour.

Moree Real Estate principal Paul Kelly said leasing was more popular than sharefarming in the Moree district, and no larger proportion than normal of landowners were looking to lease out country, despite the crippling drought of 2017-19.

“Vendors have mostly sold when they wanted to sell, and some country is being leased.

“It’s always a part of the market, but we were flat out leasing a place last year for obvious reasons.”

Mr Kelly said leases normally cover 3-5 years.

“That allows the lease-holder to get a proper rotation.”

“Sharefarming suits young people, but it’s hard to find a match with the landowner.”

He said leasing held appeal on both sides of the arrangement as land values continued to appreciate.

“The old chat for Moree is about 7pc per annum, but if you look at it over a 10-year period, it would be a lot more, even with the drought.”

“We seem to get big spikes, and then values will plateau and trade sideways.”

I would be interested in investing in land leasing

what are the possible options

A point to remember …

If you are offered Agistment, this is exactly the same as a Lease or Rent … for the Improved Land only.

Rental Yield points directly at ‘intrinsic-value’, or Fundamental Value. … depending, of course, on Supply and Demand factors.

The Agistment clauses (which point at the type of livestock, the term, and the price), are separate from any ‘Management’ or ‘Cap-Ex’ clauses … though one may off-set the other, always start with first principles.

Also, if you are offered land for 4-months at $6.00 per head per week, this is an annual equivalent rent of $2.00 per head per week.

It’s a cost-volume-profit (CVP) analysis ‘thing’ (a highly technical economics term) … as you’re bound by the limit of your Median cash-flows, and arguably subjective required rate of return above your hurdle-rate, or WACC.

I’m keen to hear the comments, please?