Dr Sally Buck is working with fellow CSIRO researchers Utpal Bose, Matthew Taylor, Jeni Pritchard, and Jean-Philippe Ral, and UTAS researchers Jakob Butler and Raul Ortega on the chickpea-protein project. Photo: CSIRO

A KIND growing season has seen Australia harvest its second-biggest ever crop of chickpeas, now being shipped in bulk to South Asian destinations, and in containers to other markets too.

Weighing in at an ABARES-estimated 1.9 million tonnes (Mt), it sits just behind Australia’s biggest ever crop of 2Mt harvested in 2016-17, and consolidates Australia’s position as — season permitting — the world’s biggest chickpea exporter.

The South Asian diaspora, and changing global diets, are already boosting global demand for chickpeas.

A further kick may come from Australia’s expanding fractionation industry, which currently uses field peas and faba beans to make plant-based protein from pulses.

How genetics, agronomy, and environment influence protein levels in chickpeas is the subject of CSIRO and University of Tasmania research findings to be presented at the 2025 Grains Research and Development Corporation Goondiwindi Update on March 4-5 by CSIRO researcher Dr Sally Buck.

The research looks to a time when grain protein, in addition to the current parameters based on moisture and appearance, may become a metric for chickpeas selling into the plant-based protein market.

The research and its findings are published in a paper entitled Breeding and growing chickpeas for market quality – preparing for shifts in market demand. The influence of genetics and growing environment on grain composition and quality for targeted market.

Following is a summary of the research:

Deeper look at established crop

Characterising the composition of diverse chickpea germplasm including landraces, varieties and breeding lines has been the first step in providing tools to breeders and growers in the event of shifts in market demand towards varieties with higher desirable proteins.

The project therefore set up a chickpea diversity panel comprising 240 different varieties using grain sourced from the ICRISAT gene bank, and supplemented with commercially available elite Australian cultivars.

Lines were grown under common glasshouse conditions and grain was harvested, then analysed for protein, soluble sugar, starch, lipid, and fibre content.

This information was used to perform genome-wide association studies (GWAS).

The proteome of eight Australian cultivars of chickpea was also investigated through measurement and counting of the amount and type of all proteins present at measurable concentrations in the seed.

Interesting lines from the diversity panel characterisation were further investigated in different environmental conditions in glasshouse settings.

One of these experiments involved eight chickpea lines, selected for varying protein content and lipid content.

These were grown under two different nitrogen conditions:

- high nitrogen, watered with a complete nutrient solution weekly; and,

- low nitrogen, watered with a nitrogen-free solution weekly.

Wide-ranging results

Characterisation of the grain composition of the chickpea diversity panel revealed large ranges in weight-by-weight composition for all measured traits as follows:

- protein 9.5-27pc;

- starch 22.3-41.8pc;

- soluble sugar 1.9-7.8pc;

- insoluble fibre 10.3-25.3pc;and,

- lipid 6.2-10.9pc.

This variation was observed in both kabuli and desi-type chickpeas, with both market classes having similar ranges of composition for all measured traits.

“This is a particularly promising result, as it suggests that lines with potentially valuable composition traits, such as high protein, could be developed in both market classes.”

“The large variation across all composition traits when grown under common conditions suggests a genetic influence.”

Because of this, researchers performed a GWAS to identify the regions of the genome associated with traits of interest; this yielded 11 regions significantly associated with grain-protein content, and spread across five of the eight chromosomes of chickpea.

“These associations present an opportunity to develop markers to assist with and speed up breeding.

“Validation of these regions as markers could support chickpea breeders in generating high-protein chickpea lines more quickly if faced with a change in market demand.”

Eight Australian chickpea cultivars were selected to have their proteins measured and counted.

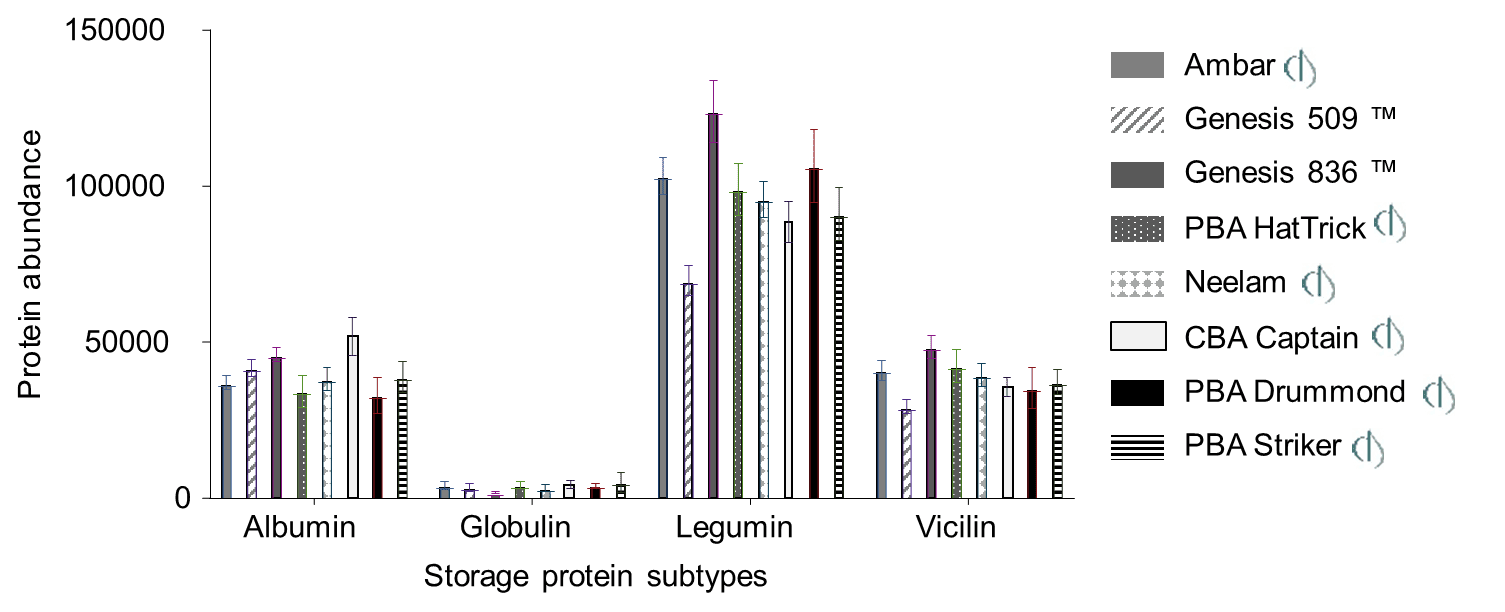

Figure 1: Composition of the main storage proteins in the chickpea proteome from eight Australian-grown chickpea cultivars.

The most abundant kind of proteins found were storage proteins, which can be characterised into different groups depending on their solubility in different solvents.

These groups also indicate some difference in the functionality that these proteins will have in food.

Legumins were found to be the most abundant storage protein in chickpeas and globulins were the least abundant.

This holds potential for food applications, as these different protein classes can perform different roles in food mixtures.

“Albumins for example are soluble in water.

“They also form foams well and can act as egg replacements, while globulins form firm gels when heated.

“Understanding the different protein profiles of the chickpeas grown in Australia will help to differentiate Australian chickpea products globally and target them to specific market segments.”

Case for applied nitrogen

Chickpeas can source atmospheric nitrogen through a symbiosis with rhizobia in their roots, so are not solely dependent on soil nitrogen.

Figure 2: Chickpea grain protein composition of seven lines grown on high-nitrogen (HN) and low-nitrogen (LN) soils. *** denotes statistical significance. ns = not significant

However, they did show significantly higher concentrations of protein in their grain when grown under high-nitrogen conditions.

This was true for all varieties tested.

These investigations of chickpea grain grown under different environmental conditions, and the subsequent scaling of these experiments to the field will give a more complete image of the factors affecting chickpea grain composition.

This in turn can be used to inform agronomic practices that will produce grain suited to specific market demands.

In the event of a strong shift towards a protein-based market for chickpeas, this could help growers maintain high-value crops until varieties with genetically determined high-protein content are available.

Investigation of the impact of nitrogen fertiliser in field conditions is currently under analysis.

Commercially available varieties were grown in the same paddock under four different soil-nitrogen regimes in the last field season.

These samples will also be processed to give insight into how they perform in food applications.

Ongoing projects are also investigating the impact of terminal drought and heatwaves on grain composition and grain protein composition.

The proteome across the development of the grain is also being investigated to understand the timing of different developmental processes in grain filling and the potential impacts of stress at different stages of grain development.

Chickpeas were the biggest pulse crop produced in Australian in the 2024-25 harvest, and a manufacturing market for them in Australia has potential to buffer its market against fickle global demand.

To register for the 2025 Goondiwindi GRDC Grains Research Update, click here.

EDITOR’S NOTE: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated soy as one of the pulses being fractionated in Australia to make plant-based protein.

Grain Central: Get our free news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY