Australia is unable to export pork to China at present, but Australian beef exports to China are up as a result of ASF, which has not been detected in Australia. Photo: Australian Pork

AFRICAN Swine Fever (ASF) continues to decimate the domestic pig herd in China with hundreds of millions of animals now lost, either dying as a result of the devastating disease or killed in an attempt to contain the spread of the highly contagious virus.

According to the Chinese government, 40 per cent of the countries pig population has been lost since the outbreak was first discovered in August 2018.

However, unofficial reports suggest that Beijing is being extremely conservative, and the world’s biggest swine herd is now more than 50pc lower than before the outbreak was announced. That equates to around 250 million pigs or almost 20pc of the global herd.

The double-stranded DNA virus causes a haemorrhagic fever with extremely high mortality rates in domestic pigs. In many instances, death can occur as quickly as one week after infection.

Infected pigs develop a high fever but show no other noticeable symptoms for the first few days. They then gradually lose their appetite and become depressed. In white-skinned pigs, the extremities such as ears, nose and abdomen turn blueish-purple. Eventually, they become unsteady on their legs, enter a comatose state and die.

The virus is amazingly resilient to a variety of curing methods and environmental conditions. There is currently no vaccine, it can endure extreme temperatures and can survive in frozen meat for several years.

Imports rise

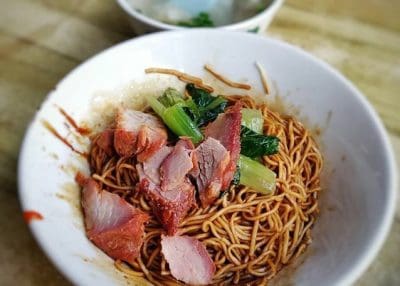

The Chinese love their pork.

It is a staple in their diet and accounts for more than 60pc of the country’s meat consumption.

In 2017, the last full year before the outbreak of ASF, they consumed an average of 33 kilograms of pork per capita. To put that in perspective, the average Australian consumed 28kg, and in the US per capita consumption was 23kg in the same year.

The significant decrease in the pig herd has led to an unprecedented shortage of pork in the world’s biggest pork market, and has seen the ex-farm price increase by more than 125pc since July this year. Retail prices are said to have increased by almost 150pc in 2019. The soaring prices have been a significant contributing factor to rising inflation in China, which hit an annualised rate of 3.8pc in October.

In a bid to meet demand and arrest the surge in prices, the Chinese Government has begun auctioning frozen pork from its state reserves. However, analysts indicate that deploying the pork reserves will not be enough to stabilise prices, let alone reduce them, and they are expected to continue rising in the run-up to Chinese New Year in January.

In a bid to meet demand and arrest the surge in prices, the Chinese Government has begun auctioning frozen pork from its state reserves. However, analysts indicate that deploying the pork reserves will not be enough to stabilise prices, let alone reduce them, and they are expected to continue rising in the run-up to Chinese New Year in January.

One of the first ASF control measures implemented across the country last year was to close down small pig farms. In a controversial backflip, and despite the continued spread of the epidemic, Beijing is asking local governments to reverse this policy in an attempt to arrest the production decline and shore up future supply.

The combination of strong demand, falling production, and spiralling prices has also put a rocket under Chinese imports.

In September 2018, China imported 94,000t of pork. In September 2019, that number had increased by more than 71pc to 161,000t, and last month, imports hit 177,500t. That pushed year-to-date imports past 1.5Mt, an increase of 49.4pc on the previous corresponding period.

In addition to traditional suppliers such as Spain and Germany, China has been scrambling to approve new import origins such as Argentina, Brazil, Ireland and the United Kingdom. In early November, China lifted its ban on imports of Canadian pork and beef that had been in place since June. This action suggests that Beijing does not want to be overly reliant on pork imports from the United States, especially as the “phase-one” trade negotiations enter a critical phase.

The increase in global trade has led to a rise in pork prices in the major exporting regions. Pork prices in the European Union, China’s major supplier, have risen by more than 35pc since the beginning of 2019. And this trend is unlikely to reverse unless there is a significant, and quick rebound in Chinese production.

One positive sign is that China’s inventory of breeding sows rose by 0.6pc in October, the first monthly increase since April last year. On the 13,000 farms with pig production of greater than 5000 units per annum, sow stocks increased by 4.7pc in October.

The total pig herd still declined by 0.6pc in October, but was much lower than the 3pc drop in September. The October number was the smallest month-on-month contraction in more than 12 months, and possibly signals the start of the recovery in the Chinese pig population. Only time will tell.

China’s government has stated there will be a 10Mt shortfall in pork supply this year, and that will undoubtedly increase next year. The challenge here is that in 2018, total global pork exports were only 8Mt.

The global exportable surplus of pork is simply too small to fill the supply shortfall.

Flow-on for beef

In a direct flow-on effect of the need for protein, Chinese imports of beef have also been increasing this year. October arrivals totalled almost 151,000t, an increase of 63pc in 12 months. In the first 10 months of 2019, beef imports were 1.28Mt, an increase of 55pc on the same period last year.

Australia does not have any pork plants approved for export to China, and authorities have been waiting more than two years to have 16 additional meat processing plants,(including pork facilities, accredited by Chinese authorities.

However, Australia does have 35 beef plants with required certification, and China’s importance as a destination for processed Australian beef has increased significantly in recent years.

With the protein shortfall in China set to continue for some time yet, Australia’s contribution to this market should continue to flourish.

This article was written by Grain Brokers Australia

Grain Central: Get our free daily cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY