THE word “climate” makes most of us look up to the sky – however, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) new special report on climate change and land should make us all look under our feet.

Land, the report shows, is intimately linked to the climate. Changes in land use result in changes to the climate, and vice versa. In other words, what we do to our soils, we do to our climate – and ourselves.

The first part of the report makes for difficult reading. Humans, it says, now exploit more than 70 per cent of the Earth’s ice-free surface, and more than a quarter of land globally is suffering degradation as a result of human activities.

Soil is being lost up to 100 times faster than it is formed, and desertification is growing year on year. Temperature increases and heavy rains associated with climate breakdown are further degrading already damaged soils.

All this is already causing food insecurity, and unless action is taken the impacts will only get worse. The report states that unless we stop and reverse land degradation, food supply chains will become unstable, and nutrient levels in foods will decrease. These impacts will hit those living in precarious situations and in poverty the hardest, but the effects will be felt around the globe.

From soil to oil

How is it possible that soils have become so degraded? Don’t we need well functioning soils to produce food? The truth is, the modern farming system is based around oil, not soil.

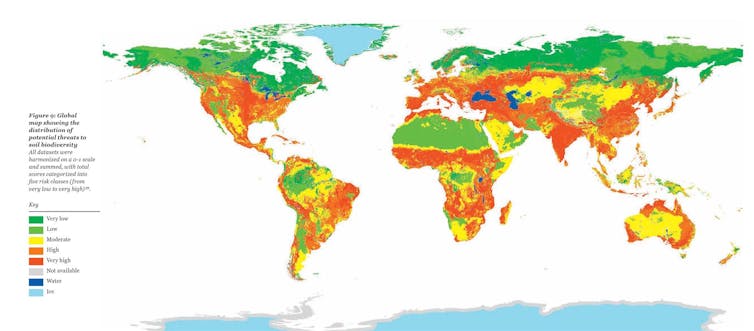

Global Soil Biodiversity Atlas

For most of our history, humans could only produce as much food as the local ecological and soil conditions could support. Every time a crop was taken from the fields, nutrients were removed, making the soil less fertile. To cope, some societies developed complex and sustainable systems in which nutrients were returned to the soil in the form of organic waste. Using the local environment and labour to maintain soils in a good state was the key to survival.

Modern farming, in contrast, has been shaped by the power of fossil fuels. The problem of limited soil fertility was overcome through fertilisation, mainly with synthetic nitrogen, which is made using natural gas or coal.

Today, emissions from nitrogen fertilisation are a major source of greenhouse gases, and the emissions produced in making that nitrogen are the biggest carbon cost in a loaf of bread.

In addition, the development of diesel-powered machinery made it possible to cultivate land which was previously inaccessible. As a result, more land is brought into cultivation, further destroying natural ecosystems such as forests. As the IPCC points out, deforestation is indeed the biggest source of agriculture-related CO₂ emissions.

Machines and fertilisers enabled more intensive farming, in which organic material is not returned back to the soil and organisms such as earthworms and microbes which make soils function are constantly disturbed through ploughing and compaction – such intensive farming leads to soil degradation and exhaustion.

Coming back to land

Until recently, the “tractors and chemicals” recipe for food production served humanity well. It drove huge increases in global yields, and made the human population boom possible. But today the extent and severity of soil degradation through human over-exploitation is such that no amount of chemicals and machinery can compensate.

Aleksandar Milutinovic / shutterstock

In Australia, years of irrigation have turned soils saline and toxic to crops. In the UK, the drained peatland soils of the Fens, which produce the most high-grade foods, are disappearing at a rate of 2cm a year. Spain, a huge producer of fresh fruits and vegetables, is in danger of desertification due to increasing temperatures and droughts. In sub-Saharan Africa, a quarter of the land is degraded, while 20pc of China’s soils are polluted. Across the world, soils have been pushed beyond their capacity to recover, and humanity’s ability to feed itself is now in danger.

To ensure that we eat well and live well in the future, we’ll need to reverse the trend towards greater homogenisation which drove food systems so far. The future is localised and diverse, because while the “tractors and chemicals” recipe worked well across the world, at least for a time, there is no easy solution for sustainable land use.

The IPCC report recognises that reversing land degradation is a socio-ecological issue, and one that requires locally appropriate action. It stresses the importance of land rights and secure access, driving home the message that land and its peoples are indivisible.

Going forward, what does “restoring land” mean for our food systems? It means supporting the invaluable bottom-up experimentation being practised by farmers and land managers and helping them develop and share their expertise. It means making sure that public subsidies to agriculture support restorative farming practices. It means working with big buyers and farmers to encourage land-stewardship and growing a greater diversity of crops. It means putting soils and their health at the centre of all land policies.

Regenerating land is a win-win, for humans and their ecosystems, if we dare to look beyond the immediate short-term horizon.

Anna Krzywoszynska is research fellow and associate director of the Institute for Sustainable Food, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The author is an climate alarmist. The reference she gives on Australia regarding irrigation turning land saline and toxic to crops is about Western Australia and saline land which was not caused by irrigation, that is just poor research. I bothered to follow the claim made regarding Spain facing desertification due to increasing temperatures and droughts, this is from a Royal Meterological Society paper :https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/joc.4519 The Conclusion starts with: The analyses of temperature trend evolution in the Spanish mainland during the second part of the 20th century identify that the maximum warming occurred in two decades (from about 1970 to 1990), but over the last 25–30 years, most of the annual and seasonal temperature trends are not significant. These findings allowed us to detect the so‐called hiatus period and its starting date, which was ascertained to be the 1990s, so the hiatus in the Spanish mainland does not only affect the 21st century. Quote ends.

Anna may be a Research Fellow, I would prefer she quotes facts and tells the truth rather than spreading alarm and despondency.

I shake my head if this is our reference point for the future of agriculture – going back to subsistence production. That wasn’t even sustainable for a human population of a couple of million let alone 10 billion plus. As a soil scientist and a farmer I think I have a fairly good handle on what modern agriculture is like and there are 3 points I would make in response to this:

1. Modern broadscale farming is VERY focused on soil health. The whole industry is built on this foundation.

2. The best way to improve the organic carbon levels of soils is to grow it and turn it in. You can’t grow it without replacing removed nutrients.

3. To reduce the amount of land that is used for human food production the best approach is to feed the most number of people from the smallest area with the greatest water use efficiency whilst improving soil health. By definition that is NOT subsistence agriculture, but it is what the modern farmer is striving for. They should be considered heroes.

Has Anna been up to date with the progress of conservation farming with little or no tillage, and the use of crop rotations -including pulses? Now over 180 million hectares world wide, including significant areas now in UK.