The agricultural industry, especially grains, has been for decades focused on productivity. We need to grow more and harvest faster. Is growing more the answer to profitability?

Growing more grain is morally the right thing to do for society. We have a burgeoning global population, rising from 4.5 billion in the mid-’80s to 7.6 billion at present. These new mouths all need to be fed, and grain is the principal food source for many.

Legions of farmers and scientists have stepped up to the plate and ensured that we have met the needs of the world. Productivity gains have been substantial during this time, with Australia as an example averaging 65 per cent higher yields in the 2010s than the 1980s.

As we stand, the world is sitting on the largest stockpile of wheat that history has ever seen. If the planet produced no wheat next year, the pantry is full enough to meet the demand for nearly half a year.

In terms of human wellbeing, this is clearly a fantastic outcome.

That being said, when inflation is taken into account, the prices received by farmers have been in constant decline since the 1970s—a victim of their own success requiring farmers to become more efficient and grow more.

Learn from the past

Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it.

In the 1930s, farmers in Australia were struggling with low commodity prices. The government of the day had the brainwave of starting the ‘Grow more wheat’ campaign. This encouraged producers to grow wheat with a guaranteed minimum price (48 pence per bushel), and grow they did.

Logic dictates that if you grow more in an oversupplied market that you end up with lower prices. In the end, the government was unable to fund the bounty and ended up paying 20 pence per bushel, resulting in approximately 20,000 farmers being forced off the land.

Let’s move forward to the present day, and although intervention in markets is a thing of the past, the pursuit of ever-increasing production gains remains a key focus.

In a previous article we looked at some potential issues around hallmark lentils. There are also another series of varieties due to be released for a superfood, which may also have issues around market capacity.

Quinoa – a new crop for Australia?

Quinoa (pronounced KEEN-WA), the superfood, has good demand. However, it remains a niche.

Recently the WA Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development released a technical dossier on a new government-funded quinoa variety.

Previously growers were restricted to growing quinoa on a contract basis. This new variety designed for Australian conditions will be available on the open market.

Australia could potentially grow large volumes of this ancient (and lucrative) grain. The question is, how much demand is there?

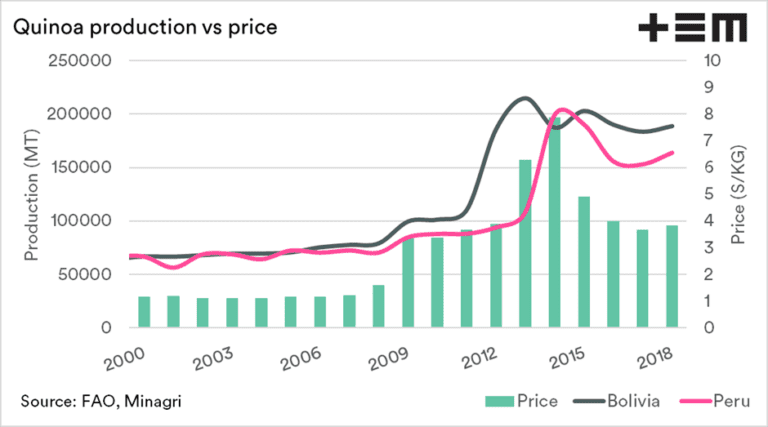

To give some insights into quinoa production, it is primarily produced in South America in Bolivia and Peru.

At the start of the decade, these two nations grew around 180,000 tonnes, in 2018 they produced 350,000t. The reason for this growth is due to demand increasing prices.

However, therein lies the problem, in these two nations. The price increases encouraged growers, which in the end resulted in too much production. Supply exceeds demand and prices fell dramatically, albeit remaining stronger than pre western interest.

If we cultivate quinoa in a big way, do we damage the global supply/demand equilibrium? If 50-100,000t of quinoa was to be grown – a minuscule amount compared to the 29 million tonnes of wheat we are forecast to grow in 2020 – it has the potential to cause quinoa prices to fall dramatically.

Growing more doesn’t always equate to better margins. We need to ensure that science is not running ahead of the market potential. Let’s remember back to when we tried to outgrow poor prices in the 1930’s.

As new crop types get added to the mix of arable commodities which growers can plant from quinoa to teff, it is important that it is understood that the niche premium is only available whilst the product remains niche.

This article was originally published on the Thomas Elder Markets website. https://www.thomaseldermarkets.com.au/

To view original article click here

A good measured article.

Growth isn’t always good, especially if its not the right product to meet the demand.

I’ve always used rice as an example when explaining the quinoa scenario. What is imported out of Peru & Bolivia is an extremely high quality seed that’s been bred naturally over 1000s of years, liken this to AAA Basmati out of Pakistan or India. Australia will never produce a rice to compete directly with a AAA Basmati, try as it may we simply won’t, the same applies to quinoa.

Like we did with rice, we need to find a variety that caters to a demand outside of the Peruvian & Bolivian high quality.