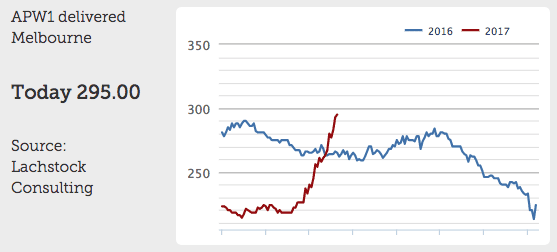

Prices for APW1 delivered Melbourne have rocketed from $220/tonne to almost $300/tonne since early June, in a rise which has surprised and defied most analysts’ expectations.

Fuelling the surge has been the lack of winter rain and risk surrounding new crop production in Australia,, and the impact of drought on projected US wheat crop production.

It has been a welcome rally for growers carrying stored wheat from last year’s 35 million tonne crop. Few are selling, preferring to hold stocks in the hope of further rises yet.

Whether that happens will hinge largely on what rain falls or doesn’t fall in key winter cropping areas in the next few weeks, analysts suggest.

Reasonable rain could bring prices back in a hurry, given the size of grower-held stocks still around and the large global wheat stockpile.

Conversely, more dry weather would see sharp downward revisions in new crop production estimates, and may push prices higher.

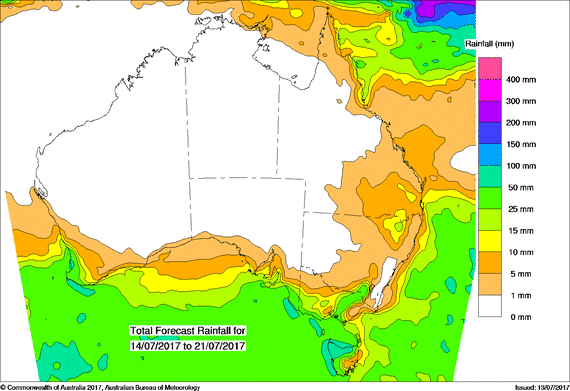

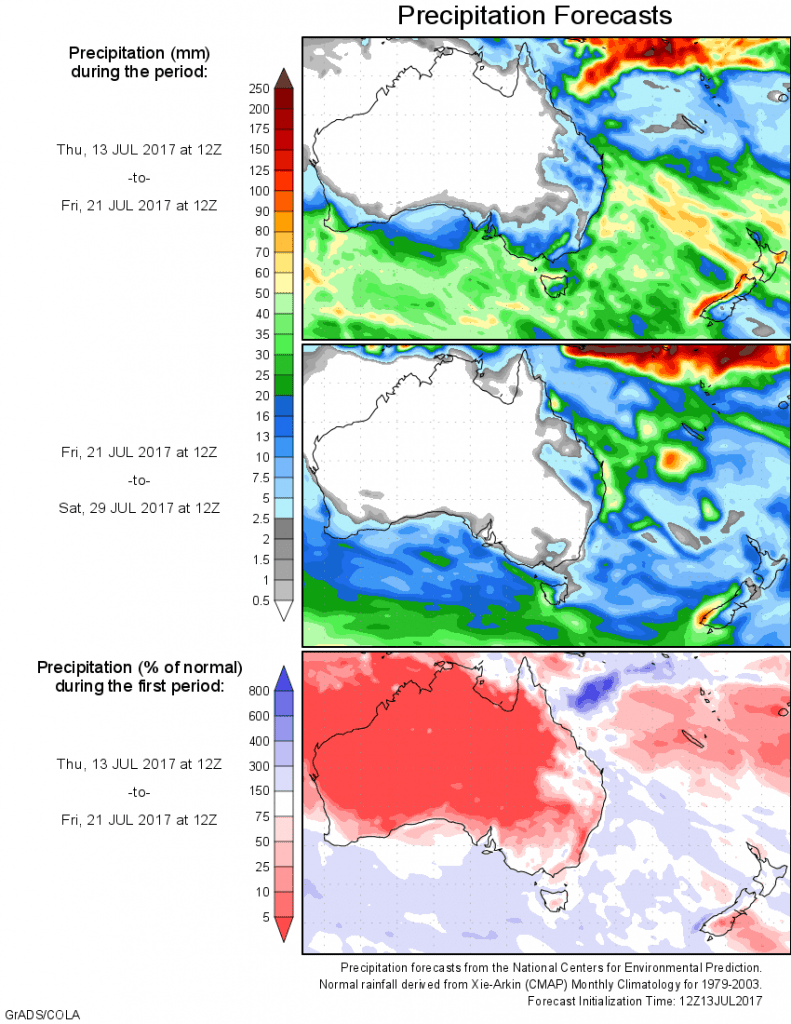

The 8 and 14 day rainfall forecasts below are not optimistic for rain:

Bureau of Meteorology’s assessment of forecast rain for the next eight days – click on images to enlarge

14 day rainfall outlook

This week’s USDA wheat crop report suggesting a slightly less dire outlook may serve to take some heat out of the market. The USDA’s forecast of US spring wheat production at 423 million bushels is higher than the 409 million expectation analysts surveyed by Bloomberg had pegged the crop forecast at.

The USDA report also raised its outlook for domestic reserves in the 2017-18 season, citing lower exports and feed use, and said the cut to world inventory was lower than expected.

For grain buyers in Australia, the current dynamics are causing supply headaches. Despite a massive wheat crop last year and significant on-farm stocks, growers remain reluctant to sell on the current rising market.

Import price parity calculations

The sharp rises of recent weeks will be prompting some analysts and buyers to be dusting off import parity price calculations, the price level at which it becomes cheaper to buy imported grain than local grain.

The interest though is far more likely to be theoretical than practical.

Australia last imported wheat during the 2002-03 drought, according to the Department of Agriculture. That involved a shipment of feed wheat from the United Kingdom. (There have also been ad hoc shipments of grain between southern and northern Australia to fill shortages during drought.)

Stringent quarantine restrictions in particular make the notion of importing grain all but unviable.

The department says it requires all imported grain to be processed (e.g. steam pelleting) at approved sites in the metropolitan area of the port of entry and has developed strict controls to manage the risks associated with discharge, transport and processing of grain.

A spokesperson for one grain processing company told Grain Central this week that imported grain could not be transported beyond 20km from the point of import. Imported grain was impossible to move and therefore not on the radar of stock feed users or mills anyway outside port locations.

In Brisbane, for example, only three grain processing mills are close enough to the port to satisfy this requirement, and are not known to have shown much interest in importing grain. More often than not pricing does not reach import parity levels, and even then switching from wheat to other grains such as barley has been a more viable option.

It is largely a theoretical exercise at this point but one that may help to add some perspective as to how far the current rally may go.

Asked by Grain Central where import parity calculations stand, Lachie Stevens from Lachstock Consulting said in reality importing grain was always harder to execute than it may appear on paper, particularly given the quarantine restrictions.

“Importing grain never really gets into practical discussions unless things get really bad, given the quarantine issues,” he said.

“Usually we run into resistance locally and traders don’t push the market up to or past import parity.”

However it was a calculation the trade tended to watch more closely during times of weather hysteria such as now.

On the question of how far prices currently are from import parity, Lachie suggested we’re “not there yet”.

Based on current local wheat prices of $325 delivered Brisbane/ $300 Melbourne for new crop local and UK feed wheat at U$230 CNF (Melb/Bri = A$300), the current difference may be the $30-$40/t cost of CNF to delivered.

HAVE YOUR SAY