Wheat crops in the northern half of NSW are expected to deliver protein levels below last year’s outstanding results.

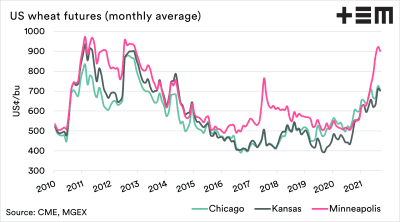

THIS year’s drought in Canada and the northern United States has pushed the premium for Minneapolis Grain Exchange high-protein wheat to around US$2 per bushel over the contract which is the global benchmark for base-grade, the CME Chicago Soft Red Winter wheat.

On paper, that equates to around A$100 per tonne, but in northern New South Wales, the heartland of Australia’s protein wheat production, the grower bid looks more like $30/t equivalent spread between Australian Prime Hard (APH) over the NSW base grade of Australian Standard White (ASW).

The reason it does not reflect the Minneapolis-Chicago spread appears to be twofold: export demand for high-protein wheat has shrunk in response to the high prices, and Australia’s domestic flour millers have stocks under them from NSW’s bumper and high-protein crop last year.

However, if this month and next are wet as forecast, NSW could be awash with lower-protein or downgraded wheat, which could blow out the high-protein premium to double or more its current level.

The wildcard is the weather between now and the end of the eastern Australian harvest, which is already well under way in Queensland and, weather permitting, will start this week in NSW.

Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre chief economist Ross Kingwell said the reduced North American high-protein crop was not enough on its own to augment the Australian premium.

“When you look back over price spreads in Australia, whenever there’s a low-volume year here, that’s when spreads blow out,” Professor Kingwell said.

The last time that happened was 2010, when rain during harvest downgraded a large proportion of eastern Australia’s wheat.

Trade shorts in the 2010 harvest market blew the APH premium out to more than $100/t, whereas last year it was under $20/t to reflect the higher-than-normal supply.

Japan, Vietnam expected to buy

Behind the domestic market, Australia’s major APH customers are Japan for use in ramen noodles, and Vietnam for its French-style baking.

Both countries are also buyers of high-protein Canadian and US wheat.

Professor Kingwell said Vietnam was typical of other South-east Asian countries in looking to the Black Sea as an alternative origin to Australia, and to supplement supplies from North America.

While the Black Sea may have more attractive FOB prices, he said Australia has the edge on freight rates.

The benchmark Baltic Dry Index hit a 10-year high in May, and has risen further since, to reflect global demand for bulk shipping.

Professor Kingwell said this was reducing the ability of COVID-impacted economies in Asia to import grain in general from far-flung origins, namely the Black Sea and North America.

“Canadian wheat is much more expensive in South-east Asia, not just because of its scarcity.

“Even though the Black Sea might have some high-protein wheat on offer, the expense of shipping it means it’s cheaper to pay a bit more for Aussie wheat because of the cheaper freight.”

Canada is usually the world’s biggest exporter of high-protein wheat, but drought reduced its spring wheat production by 41 per cent from 2020.

“Last year its spring wheat production was 25.8Mt; this year they’ve harvested 15.3Mt.”

Because North America’s high-protein wheat requirements are largely inelastic, Canada’s exports have been greatly reduced.

The premium for protein wheat over base grade has blown out to around US$2/bushel. Graph: Thomas Elder Markets

South-east Asia feels the pinch

Professor Kingwell said when high-protein wheat becomes expensive, it exceeds the budget for developing economies.

“What people often lose sight of is that…most of the customers of Australian grain are not wealthy customers.”

While COVID has hit economies hard all around the world, Professor Kingwell said its impact in South-east Asia cannot be overestimated.

“In The Philippines, just bread and cereal consumption including rice accounts for 10pc of national GDP; it’s a major cost to those economies.

“If you look at Australia, bread and cereals account for under 1pc of GDP.”

Professor Kingwell said expenditure on bread and cereals was a major component for other countries including Indonesia, Laos and Vietnam.

“Therefore they are much more sensitive to the cost of those goods.”

He said the cost of APH-type wheat, the premium segregation in an already expensive global wheat market, was prohibitive.

“When traders say they are experiencing consumer resistance, this is why.”

“In those countries to which we export, food inflationary pressures are real.”

“Any country that isn’t able to match those prices will look for substitutes.”

Importers hard to find

One trade source said new-crop APH was being offered competitively and attracting minimal interest, despite its considerable discount to the comparable Canadian Western Red Spring (CWRS) wheat.

“Ex Canada is US$360-$370/t FOB, and Aussie is $340-$350,” he said.

“We’re offering it all the time at these levels.

“The Aussie grower thinks Asian millers should be buying it because everything else is so expensive, but we’re seeing the demand isn’t getting substituted; it’s just not there.”

“People cannot import it, mill it and make money on it in Asia.

“COVID is absolutely smashing South-east Asia.”

While shipping of previously booked bulk new-crop wheat to Asia has already started ex Queensland ports, traders say the firming freight market has them cautious about booking too far into next year.

“No one will offer for January shipment today because of the uncertainty around shipping rates.”

Expensive shipping rates, a shortage of empties to pack and uncertain sailing schedules have impacted all Australian exports of containerised grain, and this may be having some impact on the lack of attractive bids for hi-pro wheat being shown to growers.

It means the delivered container terminal (DCT) market is looking surprisingly inactive on high-protein wheat, and is therefore not providing direction to the bulk market.

Different make-up

The Bureau of Meteorology has forecast a wetter-than-normal spring for eastern Australia, and falls last week of 40-60 millimetres in some areas could well make it difficult for APH varieties to hit APH1 or APH2 specifications.

These are Australia’s premium milling grades, and call for minimum protein of 14pc and 13pc respectively, while the Hard 1 and 2 segregations call for minimum 13pc and 11.5pc respectively.

ABARES has forecast Australia’s new-crop wheat production at 32.6Mt, down 2pc from the 33.3Mt harvested last year.

While the volume is little changed, Professor Kingwell said everything points to the make-up being very different to reflect the mostly softer growing season in NSW, and a bumper crop coming in Western Australia.

“This year, we’re only going to be producing 1Mt of APH, whereas last year it was 2.5Mt,” Professor Kingwell said.

AEGIC estimates put new-crop production of AH at 6Mt, down from 8.5Mt produced last year, but well up on the 3.5-4Mt produced nationally in eastern-states drought years.

While the NSW crop is forecast at 11.1Mt, down 2Mt on last year, WA’s is forecast to be up 2Mt year on year to 11.5Mt.

“WA is about to have a very high production year, and WA tends to produce a lot of ASW and APW.

“This year we are going to be producing a lot more ASW and APW.”

“The profile of the Australian wheat crop is going to be tilted towards ASW and APW and slightly away from APH.”

NSW’s 2020 wheat crop had the benefit of ample nitrogen, a result of the 2017-19 drought which prevented or minimised wheat plantings, and saw production bottom at 1.8Mt in 2019.

The NSW 2021 wheat crop will still be big, but has had less nitrogen under it than last year’s, and most growers are therefore less confident about hitting APH protein targets.

Reduced domestic APH and AH production in NSW alone is seen as mildly bullish for prices, and strongly bullish if it keeps raining.

Millers sit out

Australia’s three biggest flour millers are Allied Pinnacle, Manildra and George Weston Foods’ Mauri, and they buy direct from growers, through agents, and from the trade.

Based on varieties planted, there will be plenty of AH in all Australian states to cover their needs, around 3Mt in total of all grades for all millers, and to export.

Trade sources have told Grain Central that Allied and Mauri as Queensland’s big flour millers booked new-crop some months ago, and early crops harvested in Queensland that beat the rain have comfortably hit APH and AH parameters.

Manildra is Australia’s biggest domestic miller by far, and has a network of storages and all its milling assets in NSW, while Allied and Mauri have mills in every mainland state.

They are yet to post new-crop bids at bulk-handling receival sites, which is not unusual for this time of year.

Most NSW growing regions can produce APH, and the majority of Australian cropping regions grow AH.

This, coupled with the relatively dry season in Victoria and South Australia, means domestic flour millers can wait to see what storms rolling through northern NSW do to wheat quality before they start posting bids.

Growers ready to store

Many growers in northern NSW target APH1 and APH2 for sale to domestic flour millers or exporters.

One has told Grain Central the current APH premium over base grade did nothing to encourage expenditure on nitrogen to boost protein, especially now that urea prices have hit levels not seen since 2008.

“We spend a lot of money on fertiliser, and there’s not a big enough premium there at all to encourage us to keep doing it.”

Northern NSW producers are renowned for having plenty of on-farm storage, and this grower is one of many who said that was where his wheat would be going unless the high-protein spread widened considerably.

He said he would normally be about 40pc forward sold on new-crop ahead of harvest, but is under that this year.

“We don’t want to lock in a multigrade contract and then find we’re missing premiums for high protein.”

He is not alone, and market consensus is that the high-protein premiums will rise in NSW, even without a mass downgrading, because the NSW crop is not set up to deliver the same protein levels it did last year.

And while NSW growers sold some of their wheat straight off the header last year to get some cash into their drought-depleted accounts, they are not expected to be throwing it at the market come November.

“This is going to be the second year in a row of big crops in NSW, and farmers won’t be in a rush to sell,” Professor Kingwell said.

“Farmers are likely to retain more because they can.”

Country freight a factor

One Queensland-based trader said merchants accumulating high-protein wheat for export might be more willing to post aggressive bids if they were certain about road freight from northern NSW to the Port of Brisbane.

“A lot of traders got fairly badly burnt on Moree-to-Brisbane road freight last year,” he said.

“They put it in at $50/t, and would have paid $60/t, so that’s their margin gone.”

The trader said “the big end of town”, namely companies with international operations, wants to own high-protein wheat now, and on a delivered-port basis, which indicates export demand is healthy.

“They don’t want the responsibility of trying to get the transport to get it to Brisbane.”

He said while growers can see only upside for protein wheat, they are wary that deliveries into the domestic-focussed Stock Feed Wheat (SFW) segregation could swell.

“They’re locking in some SFW because they’re pretty sure they’re going to get some of that with this rain around.”

HAVE YOUR SAY