OPINION

IN FEBRUARY 2020 the first meaningful rainfall for over three years fell across parts of the northern Murray Darling Basin.

Towns from the very top of the catchment like Tamworth, which had been in dire shortage of water, received a reprieve from the worst drought on record.

These rains re-started rivers all the way from the head waters to the end of the Darling River at Wentworth.

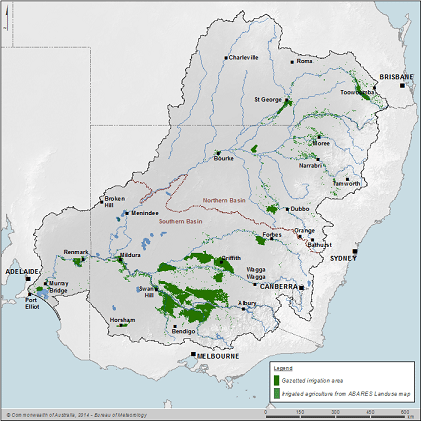

The Murray Darling Basin. (Image: BOM)

In some areas, rivers burst their banks and spilled over floodplains. After such a long dry period it was a sight to behold.

For some people in the Murray Darling Basin, the worst of the drought was over.

Unfortunately for many, the side-effects of the drought did not abate.

Due to the extreme nature of the drought and the poor state of the river system, licensed extraction of water for irrigation in the northern section of the Murray Darling Basin in NSW was embargoed, meaning irrigators were not permitted to extract water for crops, as water-sharing plans would ordinarily allow.

This was a bitter pill to swallow for irrigators who hadn’t received any water allocation for three years.

However, irrigators also fully understood the severity of the situation, and water that would normally be allocated to supplementary security license holders was allowed to freely run downstream.

These flows connected all of the northern rivers filling town storages and poured over 550,000 megalitres of water into the Menindee Lakes or, to reference an overused Australian measurement of water, just over one Sydney Harbour’s worth of water.

This ensured the Darling River downstream of Menindee would have enough water to keep flowing into the Murray for 18 months, without any further inflows into the Menindee Lakes.

It also ensured a 30-per-cent general security water allocation for irrigators in the lower Darling system, at the time, the highest general security allocation in NSW.

This was an excellent outcome for the Murray Darling river system and the communities who rely on the river for daily life.

Irrigators contributing their part

Although irrigators upstream of Menindee had not received allocations from the river flows, there was hope they were able to breathe a sigh of relief that there was water back in the system, they had contributed their part to ensure a healthier river and a lot of the public pressure on northern basin irrigation may subside.

In the Gwydir valley alone, 100,000 megalitres of water that would normally be allocated to productive agriculture was embargoed.

In dollar terms the water embargoed for environmental flows was worth $70 million at a farm gate level.

The potential value of this forfeited water to communities in north-west NSW is immeasurable following three years of devastating drought.

Unfortunately, despite the sacrifices made by norther basin communities, the criticism of irrigation did not cease. Ironically, the attacks from some parts of the community intensified.

Politically divisive

Water has always been a politically divisive issue. In times of drought the pressure on everyone on a river intensifies.

In times of flood or abundance, the desire to score political points from water policy still remains strong.

Through experience in water policy discussion, one thing has become perfectly clear.

Every single person in the Murray Darling Basin wants to see more water in their local section of the river.

Whether it is environmentalists, irrigators, graziers or fishermen, everyone wants more water.

Civilised discussion

Is it time we ALL accept there isn’t as much water to go around as there once was and set aside personal biases to ensure a more civilised discussion and workable policy development?

Sam Heagney

Droughts have been a part of the Australian landscape for all eternity and from what we are told a changing climate will mean they will occur more often and be more severe.

This makes the future of water debate even more concerning. Are irrigators going to receive a barrage of abuse and blame every time an ephemeral river naturally stops flowing from lack of rain and inflows?

Water is allocated through a hierarchical system where environmental and human needs are put first, with irrigation allocation put last.

Approximately 75pc of all inflows into the Murray Darling Basin are allocated to the environment.

Of the licenses that access the remaining 25pc of water, governments own the largest portion, which is again allocated to environmental needs.

The first people to miss out on water in dry times are irrigation farmers. Yet much of the discourse from anti irrigation lobbyists infers that dry rivers are caused by irrigation.

The loudest of these claims often come from people with either personal political aspiration or strong political affiliation.

Political football

Too often water is used as a political football for personal gain at the expense of communities along the rivers.

Herein lies the great tragedy of water policy. Small numbers of loud agitators with political ambition seek to manipulate water policy for their own gain, at the expense of innocent farmers and communities.

The first people to miss out on water in dry times are irrigation farmers. Yet much of the discourse from anti irrigation lobbyists infers that dry rivers are caused by irrigation.

Naturally politicians never miss an opportunity to score a quick point.

If cotton, or irrigation in the northern basin seems to be out of favour in the realm of urban public opinion, there is no shortage of politicians quick to fan the flames of misinformation and jump on the bandwagon.

There was even an attempt to ban exports of cotton, which would have effectively banned cotton as a crop.

Because water is allocated to licenses, not specific crop types, if successful this policy would have had zero impact on the volume of water used for irrigation, not to mention the fact that a large portion of Australia’s cotton crop is rainfed, or grown without irrigation.

The banning of cotton exports Bill was the equivalent of “some people are gluten intolerant, so let’s ban wheat farming”. It was misguided, ineffective and destructive.

Spread of misinformation

This example of political point scoring at the expense of honest farming communities shows how dangerous the misinformation and misguided efforts can be when politics becomes more important than good, workable policy.

The future of water debate and policy looks grim if in every drought those involved are going to descend into name calling, false accusations and spreading misinformation.

There was even an attempt to ban exports of cotton….. if successful this policy would have had zero impact on the volume of water used for irrigation.

Social media rants, legal challenges and manipulation of media for personal gain have no place in creating a sustainable river system where everyone receives an equitable share of an invaluable resource.

The future would look a lot brighter if everyone took some time to understand other parts of the river system and the people within it. A whole of system approach and understanding will underpin successful water policy.

Water, sustainable inland communities and healthy rivers are too important for personal political ambition. A healthy Murray Darling Basin for future generations is relying on everyone involved to be less biased and work towards more productive outcomes.

Sam Heagney grew up on the outskirts of Melbourne in Victoria. After school he worked as a jackaroo in Queensland, studied farm management at Orange Agricultural College in central west New South Wales, and worked on farms in NSW, Qld and the United States. He has also worked as a grain trader and grain broker across Australia before moving to Mungindi on the NSW/Qld border with his wife, Annette, in 2012 where he is now operations manager on her family’s property. They grow dryland and irrigated wheat, barley, chickpeas, cotton and sorghum and run a small cattle grazing enterprise.

Grain Central: Get our free cropping news straight to your inbox – Click here

A comment I would like to make is about land clearing. We have been travelling the back roads from NSW to Queensland for over 30years. One of the biggest problems I see is land clearing. Cotton and wheat use huge machinery which needs a huge turning circle, this in turn removes huge amounts of trees and scrub. Makes for a very sterile landscape, and also dries soils further. Have also seen two tractors with a chain in between raze vegetation to the ground. Don’t get me started on the loss of wildlife!!!

Cotton irrigators deserve a mega barrage The Darling cannot cope with these Hungary people I just wish it is graziers only

Although I am a farmer and an irrigator and I truly do feel for the smaller family irrigation operations that have been around for generations! but I cannot agree with this Viewpoint it would be fine for irrigators to be still taking water if the extraction levels in the northern basin was similar to that of the 1980s or 90s but I’m pretty sure The amount of water extracted these days has grown expedentially to the point that lower darling floodplains and ecosystems very rarely receive any flooding any more and are dying! It’s great that some water can be sent down the main channel occasionally but it’s the high flows and flooding that will save the environment! And I’m sure the environment is worth a great deal more than the money that would’ve otherwise been earned through irrigated agriculture “water is not all about money”

The Darling River/ Menindee Lakes have received 40% less flows since the late 90’s with the growth of irrigation in the Nth Basin ( Maryanne Slattery ex MDBA).

At the time of this article Wilcannia was on water restrictions, the Darling River had ceased to flow above Menindee.

People are not against irrigation but the greed and corruption over a long period of time by some Pigs on the River, remember the fish kills at Menindee, domestic water being trucked in to Wilcannia, Menindee, Pooncarrie.

Not only has the flows diminished but the quality of the water leading to blue green algae continuously being detected. Surely pumping could have resumed once the Darling River had connectivity and critical human needs were met, as is the MDB Plan.

A planned headline seeking act by NSW Irrigators Council, Cotton Industry, NFF and now your lot

This comment has been edited slightly to comply with Grain Central comment policy https://www.graincentral.com/grain-central-comment-policy/

Far too much water is taken at the very top of the darling basin through flood plain harvesting and pumping to fill massive private on-farm dams.

Now Sam talks about how the irrigation community done their part in reference to the water embargo well I can say that is only true in part.

Exemptions were given to large corporate cotton farms to take as much water as they could fit in their dams through flood plain harvesting which is unmetered and not regulated before the embargo was enforced.

Now with the amount of rain that fell in that rain event, if was allowed to flow freely it would have filled Menindee lakes in full not just part so that goes to show you the amount of water taken before the embargo was enforced

Now to use layman’s terms like Sam that’s 4 x Sydney harbours if Menindee was full but they received only one harbour worth of water so where did the other three harbours worth of water go ?????

Good article Sam. Unfortunate though that you seem to accept irrigators are the last to receive scarce water. Isn’t it a pity that our farmer organisations seem incapable of taking the issue of water security for general security holders up with government, especially in the Murray valley where there is lots of water but NSW irrigators out of the Murray had zero allocation for just shy of 2 years? Why is this so? Shouldn’t NSW Farmers be doing more in this area?