UK company MOA Technologies is one of several companies bringing innovation to the search for new modes of action in herbicides. Photo: MOA Technologies

ADVANCES in technology have the potential to help counter a sharp drop seen since the mid-1990s in the number of new modes of herbicide being patented.

That was the message from Colorado State University Professor Franck Dayan, who gave a keynote address on current and future prospects in herbicide discovery at the Australian Agronomy Conference held in Toowoomba this week.

Professor Franck Dayan.

Professor Dayan said consolidation of companies in the agricultural chemical industry, coupled with a focus on the development of glyphosate-resistant crops, has done little to bolster the grower’s armoury against weeds.

“Very few new mode of actions are coming out, but it’s not all bad news,” Professor Dayan said.

Among the causes for hope are the ability of traditional chemical companies and innovators to turn old and new chemistry into new modes of action, and the use of innovation coming from start-ups.

Consolidation poses challenge

Professor Dayan can see no reason for glyphosate to exit from farming systems, but said a lack of innovation caused by it being such a successful herbicide is of concern.

“Then things stand still and things go wrong and then we have these issues of herbicide resistance happening because we only have a limited number of herbicide types.”

He said a reduction in the number of R&D teams working within the industry overall had contributed to the crash in numbers of new modes of action patented so far this century.

“There’s been a really great consolidation in the agrichemical industry.”

“For 40 years, we had on average one new mode of action introduced every two years, and that held true from the 1950s to 1990s.”

“There used to be independent research groups for herbicide discovery…so now instead of 15 companies doing independent research in herbicide discovery, there’s only one company called Bayer Crop Science.

“It’s the same for BASF and Syngenta, Corteva, all the major companies.

“This provides some advantages in terms of the scale of the research they can do, but then you have fewer people actually thinking independently about various approaches to discovery.”

Professor Dayan said the success of glyphosate-resistant crops had taken the focus from the industry’s previous focus of searching for new herbicides through new modes of action.

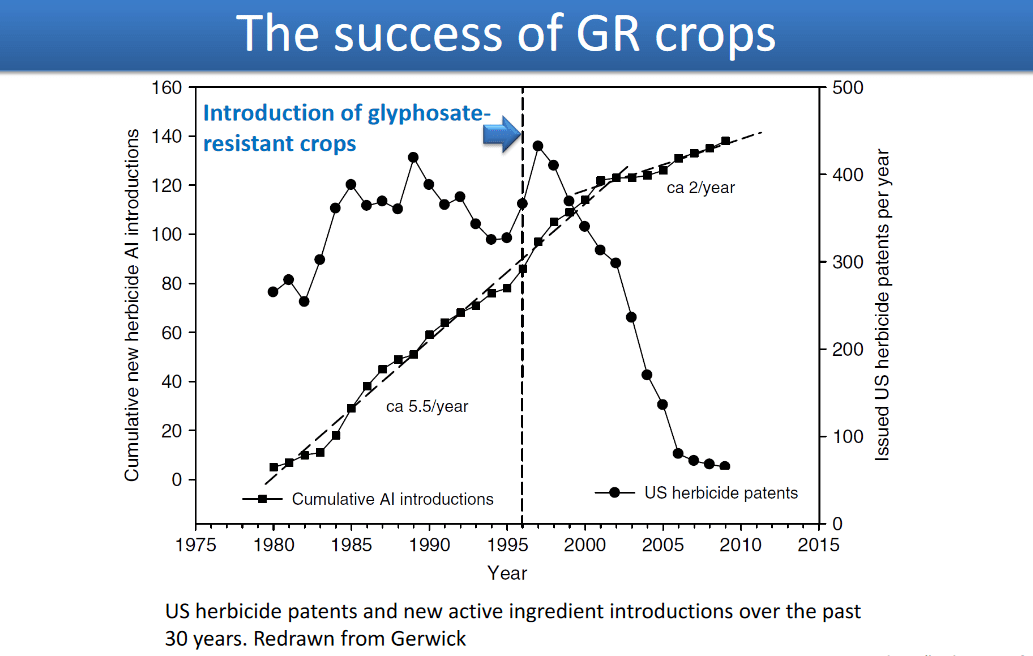

Graph 1: The rise of glyphosate-resistant crops versus the drop in modes of action patented. Source: Professor Franck Dayan, 2022

The result has been an uptrend in the number of glyphosate-resistant crops registered, while the number of US herbicide patents issued per year has crashed from up to 140 in the late 1990s to single digits by 2010.

“That’s because glyphosate is such a wonderful herbicide.”

“Once you can use it to kill weeds without killing the crops, it was a wonderful tool and it was pretty inexpensive and worked so well that there was no motivation and incentive to come up with new chemistry.”

He said glyphosate resistance has prompted a restart from chemical companies in research programs looking for new target sites in plants.

What is in the pipeline is harder to gauge.

“The problem with industry is like looking into a crystal ball; you never know what they are doing.

“All they can say is that ‘we have some really great stuff coming’.

“I wish I knew what it was.”

Professor Dayan said that for every new registered herbicide companies on average globally have to screen 160,000 compounds.

“That’s a lot of work to identify one new active ingredient.”

Professor Dayan said company’s lab results on target sites do not always translate to being effective on the plant.

“They were active in a test tube but when you go to the greenhouse, they’re not active.”

He said most companies go “back to the greenhouse” and screen 60,000 compounds a year on plants on miniaturised assays.

Innovation in action

Professor Dayan said both old and new chemistry was being investigated by corporates looking for new modes of action, and innovation was providing further promise.

“These are driven not by big companies because they tend to have used the tried-and-true method of synthesising a bunch of compounds, (and) testing on a bunch of plants until they find a hit.”

“There’s a lot of start-up companies that have new methodologies.”

One is Israeli company Agrematch, whose founders had worked as computational chemists with Monsanto prior to its merger with Bayer.

Professor Dayan has been working with Agrematch, which uses algorithms to screen its database of 10 to the power of 60 organic compounds.

“You cannot synthesise all these compounds and test them; that’s not physically possible.”

“I think this is where the technology is going nowadays.

“This company is entirely computational; first they identify compounds and then they go to the greenhouse.”

Professor Dayan is also working with MOA Technology, a UK company co-founded by Oxford University Professor Liam Dolan.

“What I like about this company is they actually work with plants, but they work with a plant that’s microscopic so they can test billions of plants in liquid cultures.

“Their technology is a good bridge between fully computational and greenhouse.”

US company Enko also rated a mention for its use of DNA-encoded libraries through which billions of compounds can be screened for targets.

“They have very strong predictive analysis.”

“There’s a whole array of new innovative approaches that hopefully in the future will keep industry, farmers, with tools to manage weeds.”

Grain Central: Get our free news straight to your inbox – Click here

HAVE YOUR SAY